Missionary of the "National Language Religion" — Wang Shoukang

Author: Yun Wang

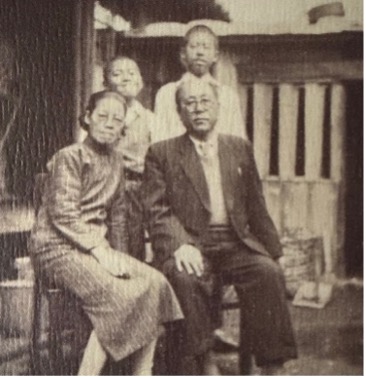

My connection with Mr. Wang Zhengfang began in 2019, and our “matchmakers” were my grandfather Wang Shuda and his father Wang Shoukang. On the back cover of Mr. Wang Zhengfang’s book “Ten Years of Wandering as a Mischievous Child,” there is a family photo. I have a copy of my grandfather’s “Beijing Normal University 1948 Graduation Album,” which contains a graduation photo of the National Language Special Training Program. The intersection of these two photos is Mr. Wang Shoukang. Thanks to the internet for connecting me with Mr. Wang Zhengfang, allowing us to embark together on a journey to commemorate our ancestors’ National Language Movement. According to seniority, I call Mr. Wang Zhengfang “Uncle Wang.” Six years later, we finally met in Beijing. Having just returned from California, I brought two letters that Mr. Wang Shoukang had written to Mr. Zhao Yuanren, which I photographed at the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. This triggered our long reminiscence and made me feel that I must write something about Mr. Wang Shoukang.

(The two photos that connected us)

Ancestors Departed, Echoes Remain

Uncle Wang, nearly ninety years old, is a true “science and engineering man.” When he clearly read out the letter that Mr. Wang Shoukang had written to Mr. Zhao Yuanren in Gwoyeu Romatzyh (National Romanization), which I had photographed, I was amazed by Uncle Wang’s foundation in Chinese literature and his memory. Uncle Wang held his father’s writing as if holding a scripture, his serious demeanor like a primary school student, pointing with his right index finger while explaining to me: “This is a letter Professor Wang Shoukang replied to Mr. Zhao Yuanren on March 8 of the 48th year of the Republic of China. He wrote in Gwoyeu Romatzyh phonetic spelling. It took me a long time to figure out how to read it. He said: ‘Mr. Yuanren, I have received your letter. Thank you for your concern. My illness has gradually improved. Please do not worry. Best wishes for your and your wife’s health. Wang Shoukang, Ward 413, National Taiwan University Hospital.’” When I discovered that the spelling of Gwoyeu Romatzyh was very similar to Hanyu Pinyin, Uncle Wang explained the rules of Gwoyeu Romatzyh to me. He said that in Gwoyeu Romatzyh, when Chinese characters are in “neutral tone” or “first tone,” there is no need to mark the tone, but for the second, third, and fourth tones, an extra letter is added to indicate the tone. He described these rules as “really fun.” I think Uncle Wang’s knowledge of Gwoyeu Romatzyh was definitely influenced by his father. In July 1930, the Gwoyeu Romatzyh Promotion Association was established, presided over by Xiao Jialin, with only about ten members at the time, such as Wang Shoukang, Du Lijin (Tongli), Wang Yuchuan, and Li Zhonghao. On January 24, 1934, Mr. Qian Xuantong wrote in his diary: “Arrived at Half-Acre Garden. Today the National Language Committee hosted a dinner for Wang Yuchuan, Wang Fuqing, and others. They are all devotees of G.R. (Note: Gwoyeu Romatzyh).” Mr. Qian Xuantong was absolutely right. Wang Shoukang, as a devotee, was not only a follower of the national language but also a propagator. In his own words, he believed in this “National Language Religion.”

Subsequently, Uncle Wang opened the photocopy I gave him of the “Overview of the Chinese Dictionary Compilation Office.” He immediately noticed that the “National Phonetic Alphabet” was the old version, with several more Suzhou phonetic symbols than they later learned, and he accurately pronounced those Suzhou sounds. When he turned to the “Staff List of the Chinese Dictionary Compilation Office (20th Year of the Republic of China)” and saw the address “No. 6 Yinliang Hutong, West Entrance of Hongmiao, West City” under his father’s name, he was surprised to find this address very unfamiliar. He thought he had found all the materials about his father… When I showed him the “1948 Beijing Normal University Graduation Album,” and he saw the photo of “Associate Professor of National Language Special Training Program” Mr. Wang Shoukang, Uncle Wang examined it carefully, murmuring: “At that time my father still had hair. Later he didn’t have a single hair left…”

Uncle Wang was like this, always joking about his father, but his words were full of nostalgia for his father. The two materials I brought him witnessed two important periods in Mr. Wang Shoukang’s dedication to the National Language Movement.

Leaving Dictionary Compilation to Follow Romance

In September 1928, the Chinese Dictionary Compilation Office, under the National Language Unification Preparatory Committee, officially began work, with Li Jinxi as director-general. Wang Shoukang, who had just triumphantly returned from the “Northern Expedition” front line, joined the Compilation Office at his mentor’s call and became a commissioned compiler in the People’s Dictionary Section of the Compilation Department, presided over by his college classmate Xiao Jialin. I have not found any dictionary that Mr. Wang Shoukang participated in compiling, because in the first few years after its establishment, the Dictionary Compilation Office mainly engaged in collection and organization work, which was completely a stage of “making wedding clothes for others.”

In 1931, Wang Shoukang’s other classmate Dong Weichuan was invited to go to Shandong as director of the Provincial People’s Education Center, dedicated to public education and literacy work. After taking office in Shandong, Dong Weichuan brought along his classmates Xiao Jialin and Wang Shoukang, one serving as editor-in-chief of the Shandong “People’s Weekly,” and the other as director of the People’s Cinema. Dong Weichuan and Xiao Jialin also had another relationship—they were brothers-in-law, having married the Kong Wenzhen and Kong Fanjun sisters respectively. Wang Shoukang at this time also began his romance with Miss Cao Duanqun, the former director of the cinema. When they married in 1935, there was a wedding song: “Fuqing and Duanqun, Duanqun and Fuqing, met and loved, united and blended, upstairs and downstairs, deep feelings between two, in front of and behind the donkey, devoted and diligent, until today, great success achieved, packed in a jar, endless happiness.” Among these, “upstairs and downstairs” referred to the fact that the third floor of the People’s Education Center cinema was staff dormitory, and downstairs was the screening room—during film screenings, they would be busy going up and down the stairs; “in front of and behind the donkey” referred to traveling by donkey when going on outings, with Duanqun on the donkey and Fuqing walking alongside; “packed in a jar” referred to their address at the time, “Jar Alley.” From this perspective, leaving the Dictionary Compilation Office, Wang Shoukang gained quite a lot. Of course, his work was equally important—showing films was an important means of spreading the national language. You should know that Shandong was the most successful place in promoting the national language and popular education, which cannot be separated from the contributions of Dong Weichuan, Xiao Jialin, Wang Shoukang, and others.

Teaching at Normal University, Continuing the Mission in Taiwan

Let’s talk about the “National Language Special Training Program,” which was established after the victory of the War of Resistance specifically to train teachers to go to Taiwan to teach the national language. At that time, Wang Shoukang accepted the call of Mr. Li Jinxi and served as an associate professor in the National Language Special Training Program at Beijing Normal University. He and his junior fellow students Wang Shuda, Sun Chongyi, Niu Jichang, Xu Shirong, and others trained dozens of graduates at the fastest speed. After assessment, they went to Taiwan to engage in national language teaching. Later, many of them maintained close relationships with Mr. Wang Shoukang, who also went to Taiwan. Uncle Wang could recognize seven people from their 1948 graduation photo: Da Song (Song Mengshao), Zhang Boyu, Zhao Wenzeng, Zhai Jianbang, Gong Qingxiang, Huang Zengyu, and Feng Changqing. These people became seeds for Taiwanese people to learn the national language. Wherever they took root and sprouted, the flower of the national language would bloom there.

Back then, it was very difficult for these students to be selected to work alone in Taiwan. Mr. Wang Shoukang particularly cared for these young people. Every New Year’s Eve, they would go to Mr. Wang’s home together for the New Year’s Eve dinner and make dumplings together. These young men from the north were particularly skilled at rolling dough, making dumplings, and cooking them. After dinner, everyone would play bridge together, drink tea and chat, lively until late at night. Teacher Wang was like everyone’s parent. They could talk about anything, except they couldn’t mention changing careers. Once, Zhang Boyu joked: “Teacher Wang, look at how capable all of us brothers are. Why don’t you lead us to start a company and make money together? Can’t we stop doing language education?” Mr. Wang harshly scolded Zhang Boyu and warned everyone: “No matter how hard it is, you must continue with language education, because what we believe in is this National Language Religion.”

Someone came to Teacher Wang late at night to borrow money. Teacher Wang asked the reason and suddenly raised his voice: “Did you go wild and get into this mess?” The person quickly denied it. However, scolding aside, Mr. Wang would still help him solve the problem. For a while, Da Song was implicated in a “bandit spy case.” Almost none of the classmates from the National Language Special Training Program were spared; everyone was arrested, some for two or three months, and some even lost contact. Mr. Wang served as guarantor for all the students, promising they would be law-abiding in the future. During that period, Mr. Wang became a regular visitor to the political prisoner detention center on Aiguo East Road in Taipei, until he bailed out everyone who could be released. The shortest person among them waited for Mr. Wang to bail him out at the detention center, but the release document was delayed for several days. He was extremely anxious, and when he saw Mr. Wang, he said: “Teacher Wang, if you hadn’t come, I would have been like Wu Dalang becoming emperor—no one to guarantee!”

At that time, Wang Shoukang went to Taiwan accepting the commission from Wei Jiangong, then director of the Taiwan National Language Promotion Committee, to bring the lead type copper molds and publishing equipment of the “National Language Tabloid” to Taiwan to run a newspaper. Originally a three-year term, he ended up staying in Taiwan permanently due to political changes. Wang Shoukang was the first deputy director of Taiwan’s “Mandarin Daily News.” From having nothing at the beginning to now, the newspaper has been published continuously for more than 70 years, and almost all Taiwanese people grew up reading the “Mandarin Daily News.” Later he went to Taiwan Provincial Normal University, continuing to run the National Language Special Training Program and cultivate language education talents. Taiwan’s children’s literature masters such as Lin Liang, Fang Zushen, Zhang Xiaoyu, and Wang Tianchang were all his students. In 1956, Taiwan Normal University established the “National Language Teaching Center,” with Wang Shoukang as the first director. This center has successively trained hundreds of thousands of foreign Sinology experts, such as Shi Qingzhao, who were deeply influenced by Wang Shoukang. The ideals of Mr. Li Jinxi and other predecessors of the National Language Movement were deeply rooted in Taiwan by Wang Shoukang and others, making Taiwan the greatest beneficiary of the National Language Movement.

A Talented Scholar from Wuyi, Persevering Through Adversity

Wang Shoukang, styled Fuqing, was from Qingzhong Village, Wuyi County, Hebei Province, born on February 15, 1899. His father made a living by venturing to Manchuria to do fur business, establishing some foundation for the family. When he was born, there was a famine, and the family survived on a few liters of miscellaneous grains and grain husks. The name “Shoukang” meant “longevity through husks.” He was clumsy with his hands and feet since childhood and was not good at farm work, but he was eloquent, learned characters quickly, and was accurate at keeping accounts. Therefore, his uncle, as the head of the family, decided to send this child to school. Sure enough, Wang Shoukang lived up to expectations. Not only did he break records in county elementary school, but he also got into the most difficult school to enter—Beijing Normal University High School—and then Beijing Normal University, becoming the first college student from his home county. In middle age, Wang Shoukang still carried with him the cup his uncle used to brew opium paste. He believed that without his uncle’s keen eye for talent, he would have been just another Hebei farmer buried in the yellow earth.

However, Wang Shoukang’s luck wasn’t entirely good either. When taking the college entrance examination, he took it three times before getting into Beijing Normal University’s Chinese Department, not because his grades weren’t good, but because in his application photo he looked dark and thin, and with his “long robe, mandarin jacket, and melon-skin cap” matched with a grand teacher’s chair, water pipe, and covered teacup, he looked like a middle-aged man, and the examiners thought he was too old. Fortunately, Teacher Xia Yuzhong argued at the examination committee: “This student has applied three times, and his grades have been excellent each time. His persevering spirit is very admirable. Although he appears to be older, his determination is commendable and his coursework is solid. Normal University students’ age need not be too strictly limited. Being older doesn’t matter—after graduation he’ll be a teacher anyway!” Yes, the 1920s were the most brilliant era of the Republic of China, with academic freedom and openness. It was by borrowing this spring breeze that Wang Shoukang was able to attend Beijing Normal University and receive the true teachings of masters such as Li Jinxi, Qian Xuantong, and Huang Kan.

If the twists and turns of the college entrance examination were a kind of teasing, Wang Shoukang’s subsequent ups and downs in life were entirely of his own making. Upon graduating from college, Li Jinxi arranged for him to teach at a certain middle school in Beiping. On the first day of class, he was nervous enough. Facing a room full of students, Wang Shoukang pretended to be calm and first took attendance, loudly reading out the first name: “Seating Chart!” After three times, what he got was a roar of laughter. Yes, Mr. Wang at this time was somewhat pedantic, and also impatient and liked to fight injustice. When he saw the school making up names and randomly collecting money from students, he actually organized students to protest, completely unable to figure out who his benefactor was. The result was naturally that he was “encouraged to seek other employment.” Wang Shoukang himself didn’t care. He had his own sense of right and wrong. Once, he discouraged students from joining a certain political group. One morning when he hadn’t gotten up yet, a crowd gathered outside his dormitory shouting “Down with Wang Shoukang!” After being woken up, he replied in a loud baritone: “No need to overthrow me, I’m still lying in bed!”

In this way, this “accident-prone” Wang Shoukang, for a period of time, taught at any one middle school for an average of no more than two months. However, he had a backer—his teacher Mr. Li Jinxi. Mr. Li Jinxi not only taught at Beijing Normal University but also held a position in the Ministry of Education. He could be said to have extensive connections in the education world and could always find another teaching position for Wang Shoukang. Who would have thought that Wang Shoukang was still not satisfied and actually went behind his teacher’s back to abandon literature for the military, going to Guangzhou to join the National Revolutionary Army to participate in the Northern Expedition. As a clerk in the army corps headquarters, he personally experienced the most brutal battle of the Northern Expedition—the Battle of Longtan. However, when he told his children about this battle, he underplayed it as if children were playing war games, greatly disappointing the children. From this, Wang Shoukang’s optimistic attitude was evident.

After the victory of the Northern Expedition, Wang Shoukang returned to Beiping and resumed his proper profession. He taught at Beiping Women’s Normal University and Peking University Law and Commerce College and was summoned by Mr. Li Jinxi to the Chinese Dictionary Compilation Office. Later he went to the Beiping Public Affairs Bureau and in 1931 went to Shandong. In 1934, when the Shandong People’s Education Center cinema was changed to Provincial Theater, Wang Shoukang and his romantic interest Cao Duanqun left Shandong, going separately to Tianjin Pozhen Normal School and Beiping Fulun School to teach. In 1935, they established a new family together in Beiping. For some reason, Wang Shoukang later went to Nanjing to serve as Director of Education for the Tianjin-Pukou Railway Bureau of the Railway Ministry. He really was quite restless.

Spreading the “Religion” in the War Zone, Full of Passion

In 1938, after the outbreak of the War of Resistance, the passionate Wang Shoukang joined the military again, serving as an instructor and leader of a battlefield work team in the Third War Zone of the Southeast. He ran newspapers, broadcast anti-Japanese messages, ran soldier literacy classes, and led drama troupes everywhere to publicize the war of resistance. Most worth mentioning is Wang Shoukang teaching new recruits to read, which happened at the foot of Ehu Mountain in Hekou Town, Yanshan, Shangrao, Jiangxi. Most of the new recruits were locally conscripted farm boys who had not received any education, could only speak the local dialect, were basically illiterate, and some couldn’t even distinguish left from right. Wang Shoukang compiled a set of “New Recruit Literacy Textbook” himself, first teaching them to memorize the 37 phonetic symbols and learn pinyin, then teaching them to recognize characters, with each character accompanied by phonetic symbols to help with pronunciation. After several months, the new recruits’ literacy achievements were remarkable. Wang Shoukang was very excited and often called out several students with good grades to speak a few sentences loudly, shocking the entire audience with their proper pronunciation. It was a difficult period—not to mention the hardship of life, the war situation was precarious, not knowing when the Japanese army would attack. Wang Shoukang didn’t care about that. He saw the recruits go from knowing nothing to being able to read and express themselves, learning how to conduct themselves in society, and felt his achievements were extraordinary. He believed that cultivating them to become useful people for society was his greatest contribution to the country.

Wang Shoukang’s sense of mission came from his teachers. When he was still studying at Beijing Normal University, the National Language Movement led academically by Peking University and Beijing Normal University was in full swing, and the slogan “unity of spoken and written language, unification of national language” had already become deeply rooted in people’s hearts. He and his classmates understood and believed in this movement far more than others. They worked hard to practice the propositions of the National Language Movement and promote its achievements—phonetic symbols, standard national pronunciation, and Gwoyeu Romatzyh. Wang Shoukang chose the most difficult and wandering environment, facing a group of the most difficult students to educate.

Wang Shoukang served as a broadcaster twice in his life. The first time was during the War of Resistance at a radio station in the Southeast War Zone, mainly reading current affairs articles, and later also reading his own “Frontline Diary.” At that time, communication equipment was simple and primitive, and electricity had to be generated by human power by stepping on a bicycle-style pedal. The radio station was set on a mountaintop because mounting the antenna on the mountain would allow the signal to travel farther. Broadcasters needed to go to the mountaintop for live broadcasts, and there was almost no road up the mountain. On rainy days, they could only roll and crawl up. If unlucky, they would be bitten by snakes or even followed by tigers. One New Year’s Eve, the broadcast ended very late, and Wang Shoukang went down the mountain with his orderly. They lost their way when passing through a mass grave. It was dark and cold, and they didn’t recognize the way home until dawn broke. The orderly praised Officer Wang for being brave, talking and laughing all the way. Wang Shoukang told him: “People shouldn’t fear ghosts; ghosts fear people, because people have righteousness.”

Many years later in Taiwan, Professor Wang Shoukang had a regular program teaching the national language at the China Broadcasting Corporation on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. He would read a passage from the “Mandarin Daily News,” give a brief explanation, and Lin Liang beside him would explain it again in Minnan dialect. Compared to being a broadcaster the first time, this was practically paradise.

During the War of Resistance, theatrical performances on mainland China were most popular. Wang Shoukang was once the leader of a certain drama troupe, leading the troupe all over Hunan and Jiangxi. The repertoire performed there included Lao She’s “Country Above All,” Cao Yu’s “Sunrise,” “Put Down Your Whip,” and others, promoting the war of resistance. Although he was neither a director nor an actor, he sometimes would guest-speak lines backstage. Once he guest-starred as a screenwriter, with his friend as director, staging a play for Shangrao Zhongzheng Elementary School. His sons Wang Zhengzhong and Wang Zhengfang played actors, one playing Mussolini and the other Hitler, getting to be actors for the first time. Perhaps at that time Wang Shoukang planted the seed of making movies in Uncle Wang’s young heart.

After the victory of the War of Resistance, Wang Shoukang’s college classmate was the director of the Social Affairs Department of Hebei Provincial Government and pulled him to help, an offer difficult to refuse. At that time their workplace was in Baoding. Wang Shoukang was responsible for transporting relief supplies from UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) shipped from the United States in batches from Tianjin Port to disaster areas. Seeing the tragic conditions in the disaster areas and the things donated by Americans, Wang Shoukang couldn’t help but sigh: “We have won, but now both Japan and China have become America’s adopted sons. I heard Japan is already recovering and rebuilding, but we’re still continuing destruction, fighting and killing endlessly. In the future, that Japanese adopted son will do better than us—how embarrassing!” His view on “Leader’s Works Study Week” was: “We study for one week and rest for one year.” In short, it would be strange if someone like him did well in officialdom.

Spreading the “Religion” Through Newspapers, Becoming Household Name

It was Mr. Li Jinxi again! This time he called Wang Shoukang to run the “National Language Tabloid,” finally returning to language education. This newspaper was used to promote the national language. It was very special—every character had phonetic symbols beside it. As long as one learned the phonetic symbols, one could read it. It was suitable for primary and secondary school students and readers engaged in literacy education. The newspaper office address was on Xuannei Street, not far from Beijing Normal University. Wang Shoukang was finally able to settle down in Beiping. He was the deputy editor of the newspaper, with Xiao Jialin as chief editor, his old acquaintance. Other editors or contributors included Xu Shirong, Wang Shuda, Sun Chongyi, Niu Jichang, and others, all top students of Li Jinxi and also Wang Shoukang’s junior fellow students. They later became colleagues, teaching together in the National Language Special Training Program at Beijing Normal University under Mr. Li Jinxi.

It seemed as if Wang Shoukang hadn’t lived if he didn’t move once every year or two. In 1948, he was again ordered to bring the lead type molds of the “National Language Tabloid” to Taiwan by sailing through wind and waves, beginning his career of spreading the “National Language Religion” in Taiwan. It should be said that this was also his greatest achievement in life.

When the “Mandarin Daily News” was founded, the director was Hong Yanqiu, the chief editor was Liang Ruoruo, and the deputy director was Wang Shoukang. The newspaper office was located in the former “Kenkō Shrine” in the Botanical Garden. The working conditions at that time were very difficult. Typesetters had to hold manuscripts and typesetting trays, walking around in dark rooms to do typesetting, and everyone was particularly busy. Due to insufficient funding and lack of personnel at the newspaper, only Wang Shoukang had worked at the “Frontline Daily” during the War of Resistance and was considered experienced. Therefore, he had to manage all matters, big and small, inside and out. On October 25, 1948, after going through countless difficulties, the inaugural issue of the “Mandarin Daily News” came out. At that time, the newspaper was only a small sheet, and young Uncle Wang ridiculed it. Wang Shoukang solemnly told his son: “Language education is sacred. A newspaper with phonetic symbols is the only one in the world.”

As soon as the “Mandarin Daily News” was published, it faced sales problems. They also received notice from the Ministry of Education that funding would no longer be allocated and they had to find their own way. In fact, the Ministry of Education had only given 10,000 yuan in gold yuan certificates, which depreciated quickly and had been spent long ago. Unexpectedly, the newspaper had just started up and was facing bankruptcy and closure. At this time, the lead type copper molds with phonetic symbols that Wang Shoukang had brought from the mainland brought a turnaround for the newspaper. It turned out that the Taiwan Provincial Department of Education wanted to print 300,000 copies of “Three Principles of the People” and “Fundamentals of National Reconstruction,” requiring phonetic symbols, and at that time only the “Mandarin Daily News” in Taiwan could publish them. The lead type copper molds actually became the core competitiveness of the “Mandarin Daily News”! Initially, it was precisely to escort this set of copper molds that Wang Shoukang traveled from Tianjin by ship and entered Taiwan through Keelung Port. A copper mold was a copper rectangular mold used to manufacture printing lead type. By pouring molten lead into the mold and letting it cool, a piece of lead type for printing could be manufactured. There are four or five thousand commonly used Chinese characters. A complete set of copper molds requires ten or twenty thousand molds because newspaper printing has different fonts and sizes. Making this kind of mold was a complex task promoted by the National Language Committee. First, everyone completed the common character list by voting, then found manufacturers to make molds according to the character list. Because this kind of mold had high manufacturing costs and low usage rates, civilian publishing institutions were unwilling to invest. The National Language Committee had to apply to the Ministry of Education for production funds. Therefore, at that time there were only two sets in all of China.

The “Mandarin Daily News” barely survived the first year. The anniversary was approaching, and Deputy Director Wang said: “Although we are poor, we should still celebrate properly.” So the newspaper held a banquet in the photography studio of another institution in the Botanical Garden—the Taiwan Film Studio—with more than a dozen tables set up and a small stage arranged. Deputy Director Wang gave some words of thanks and old jokes, and everyone laughed nonstop. Finally he said: “The newspaper hasn’t been well-off this past year. Today’s banquet is very simple, without big fish and meat. I’m providing everyone with my favorite New Year’s dish from my childhood. I could only eat this during New Year in my old home in Hebei. Let’s eat this today. Eat as much as you want tonight. I guarantee there’s enough and I guarantee it’s delicious.” It turned out that in the middle of each table was a large washbasin containing Chinese cabbage, vermicelli, tofu, radish, and chunks of pork belly stewed together—just this one dish. This was Deputy Director Wang’s favorite. His love of eating was as famous as his love of giving speeches. However, this meal really lived up to his saying: “Let’s call this ‘poor but happy’!”

Wang Shoukang lived a poor life, but he was always full of enthusiasm and optimism. After coming to Taiwan, someone once introduced Wang Shoukang to teach Chinese at Nanyang University in Singapore. The temptation of high salary made him waver for quite a while, but this time he was very firm because he had promised his mentor Mr. Li Jinxi to devote himself wholeheartedly to promoting Chinese language education in Taiwan. He later became a professor at Taiwan Normal University and Political Warfare School, cultivating a large number of national language talents. The National Language Teaching Center at Taiwan Normal University, which he directed, further promoted the national language cause to the world.

Master Speaker with Moving Eloquence

In Uncle Wang’s description, Wang Shoukang’s image was not tall, and he was somewhat wooden. He was short in stature, had a not-small belly, sparse hair, giving a stocky impression, and from a distance looked exactly like a northern farmer. His round horn-rimmed glasses always sat on the tip of his nose, and his clothes and pants were worn loosely. However, he also had his spirited moments: After the victory of the War of Resistance, wearing his National Army uniform with colonel rank, striding into his family’s “Yongxincheng” fur shop—he was so majestic! Also, he himself talked about his appearance when skating in college: wearing a fashionable dark fox fur-lined long robe, wrapped in a white scarf, going to Beihai to skate with companions, suddenly doing a single-leg jump, making a 360-degree turn, landing back on the ice and continuing to glide with arms extended and one leg stretched out flat. People watching applauded loudly—so handsome! However, no one could verify his description of himself. But one thing was certainly true: Wang Shoukang was always word for word, speaking eloquently, gesturing very exaggeratedly, laughing heartily, with great vocal volume. He hated evil like an enemy, and when angry he was like a rocket, roaring impressively. When tired, he also liked to sing a section of Hebei Bangzi opera to cheer himself up. He was strong and resilient. He had a famous saying: “Being scolded doesn’t hurt, so why feel bad?”

Wang Shoukang was not only a linguist but also an orator. His linguistic talent was innate. Whatever the matter, he could speak it out spontaneously in rhythmic and rhyming form. For example, when children ran around the house, he would happily say: “Jumping and frolicking making noise, can’t buy it in Shanghai.” When encountering entangled matters, he would wave his hand: “What’s this all about, blue underpants!” He encouraged young people to express themselves boldly and not be “like Wang Xiao celebrating New Year—having no words (paintings)” at critical moments. When making a wasted trip, he would mock himself: “I’ve become like a dung beetle meeting someone with diarrhea—a wasted trip.” To people who loved to complain, he would reprimand: “Don’t be like a fly in confinement, carrying a bellyful of grievances (maggots)!” However, his sharp language was also very powerful. If subjected to his severe scolding, it could be more painful than being beaten.

Uncle Wang remembered when he attended Normal University Second Affiliated Elementary School in Beiping, the principal invited his father to give a speech at the school, and everyone sat in the classroom listening to the broadcast. Wang Shoukang told his classmates about his experiences during the War of Resistance—being bitten by snakes while walking mountain paths, tigers roaring behind him, Japanese planes strafing at Wuyi Mountain… vivid imagery, rich language, full of witty remarks. Many students crowded outside the broadcast room to listen, eager to see what this Uncle Wang who was so good at telling stories looked like.

Every time Wang Shoukang came home from work, children from the streets and alleys would swarm up, calling out one after another: “Uncle Wang, tell us something, tell me first!” He would casually say a sentence or two, things like “Little He, Little He, full and not hungry, just afraid of art class” or “Little San, Little San, eating dried radish, pooping red and smoking red” and such. His ability to compose children’s songs was related to his childhood growing up in northern mainland China. Northern rural children’s songs have resonant tones, humorous language, vivid descriptions, and are unforgettable once heard.

Of course, as a professor of Chinese, Wang Shoukang didn’t just amuse children. His pronunciation was pure, his voice full of vigor, he spoke with ease and composure, humor and wit, commenting on the world, evaluating affairs of state, narrating stories, with witty remarks flowing like pearls, utterly masterful. It can be said he had reached a high level of linguistic artistry. He once gave a speech at the wedding of “Mandarin Daily News” editor Lin Liang and Zheng Xiuzhi: “These two people’s names form the four characters ‘Xiulin Liangzhi’ (Beautiful Forest Good Branch). Not only will they have harmonious marriage, but their children will certainly be outstanding. This is a match made in heaven.”

In Taiwan, Professor Wang Shoukang often gave lectures touring the entire province, becoming well-known far and wide. He also published a book “Ten Lectures on Public Speaking.” When Uncle Wang was in middle school, every time the school participated in speech competitions, teachers would ask Professor Wang Shoukang to coach the school’s participating students. Zhao Youpei, in commemorating his old friend Wang Shoukang’s wonderful oratory, described: “As soon as he stepped onto the podium, he was magnificent and thorough, unable to stop, yet able to explain profound things in simple terms, with witty remarks like pearls, delighting the audience who were all smiles and raising eyebrows, laughing constantly, with applause erupting.” He praised Wang Shoukang as “a man of iron bones who was loyal and straightforward, open and honest, distinguishing between public and private, poor but unyielding, the poorer the harder, masculine in character, selfless in work, cynical about the world. Language education was his strongest conviction.” Wang Shoukang’s last lecture was touring the province with Zhao Youpei in 1959. He unfortunately suffered a stroke in Hualien. Lin Haiyin once recalled: “Mr. Fuqing had a stroke, and like typical stroke patients, one side of his body was paralyzed and unable to move, unable to speak. This was truly a tragic thing for Mr. Fuqing, a language professor and orator… Every day I saw him wearing a long robe, with half his body askew, limping, struggling to learn to walk.”

Uncle Wang’s mother once sighed to her son: “It was all caused by giving speeches. Your father loved to lecture, that energy on stage, that excitement and ease, the enthusiastic response from the audience below—he really couldn’t let it go, forgot the time, and even more couldn’t care about his own body. No one could stop him.” In Uncle Wang’s mind, his father was always a true master speaker. Because the primary condition for a master speaker is to speak a certain language accurately, and only then comes erudition of words, wit, humor, rich content, clear logic, mastering appropriate pacing and emphasis, hitting the key points, making listeners feel as if enlightened.

Connected to the National Language, Repaying the Teachers

In 1971, Uncle Wang met his father’s old friend Mr. Wei Jiangong in Beijing. He told Uncle Wei that his father had been severely disabled by stroke for more than ten years. His brother Fuqing, who had once been skilled in linguistic arts, humorous, widely read, and able to astonish with his eloquence, had since lost his ability to speak. Mr. Wei Jiangong fell silent for a long time…

Wei Jiangong, who hadn’t seen him for many years, still had deep feelings for Wang Shoukang, which shows his personal charisma. After Professor Wang Shoukang had his stroke and couldn’t work, Taiwan’s social welfare was quite backward at the time, with no insurance or retirement security system. His two sons were both studying in the United States, and the whole family fell into financial difficulties again. Professor Wang’s students Zhang Xiaoyu, Fang Zushen, Wang Tianchang, Huang Zengyu, Zhong Lusheng, and others, who already had university qualifications, reached an agreement with Taiwan Normal University to teach classes for Professor Wang at the university voluntarily, enabling Mr. Wang Shoukang to both retain his professorship and obtain income. Every month, they would visit their teacher and respectfully hand an envelope to their teacher’s wife. This continued for five years, until Uncle Wang and his brother found work.

In Wang Shoukang’s last few years of life, the ones who took care of the elderly couple the most were the Xia Chengying and Lin Haiyin family, simply because they were neighbors. Wang Shoukang’s classmate Mr. Liang Ruoruo once wrote in an article: “Shoukang was broad-minded and magnanimous, frank and sincere, and liked to help friends and young people in difficulty. He taught many students. Early morning, noon, late night, weekends—groups of three or five could visit him anytime. Discussing learning, careers, family life, romance—he would listen carefully and answer seriously. ‘A classics teacher is easy to find, but a moral teacher is hard to seek.’ He was a rare moral teacher.”

Mr. Zhong Lusheng, who graduated from Taiwan Normal University, wrote an article recalling his teacher: “Nine years ago, Teacher Wang Shoukang gave us our first lesson. He began by explaining the two major goals of the ‘National Language’ movement: unity of spoken and written language, and unification of national language. He recounted the successes and failures of the National Language Movement, sometimes jumping up with joy, sometimes hanging his head in dejection, sometimes gritting his teeth, sometimes in painful sorrow. I saw his forehead glistening with light, his trembling hands flying in the air, his short stout body shaking vigorously back and forth, his mouth ceaselessly eloquent. At that moment, a surge of energy filled my chest. I clenched my fists, gritted my teeth, and was moved by his emotions. Looking at the classmates in front, behind, left and right, every one of them was listening intently, impassioned. We deeply admired his enthusiasm for language education and his outstanding oratorical talent!” When Teacher Wang was in his hospital bed and Zhong Lusheng told him that the students wanted to establish a civilian organization to promote the national language, Wang Shoukang kept saying “yes, yes!” gesturing continuously with both hands, and finally managed to say two words with his thumb raised: “Very good!”

Mission Unaccomplished, Merit for Millennia

In June 1954, Wang Shoukang wrote to Mr. Zhao Yuanren in the United States, lamenting that the comrades of the National Language Movement had scattered. “Haven’t heard from Dichen and Zijin for five years, Mr. Shaoxi dare not do any activities, Mr. Wang Yian is approaching eighty, working hard in Taiwan to train shorthand personnel…” He believed that the promotion of the national language in Taiwan had achieved considerable success and mentioned Liang Ruoruo, Wang Yuchuan, and Qi Tiehen who were promoting the national language in Taiwan. The original of this letter is now preserved in the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley.

Uncle Wang graduated from the Electrical Engineering Department of National Taiwan University. His ability to become an excellent director and actor was not unrelated to his father, and his genes for humor and wit also came from his father. Wang Shoukang loved his sons very much. In 1954 he wrote to Zhao Yuanren, and actually one important matter was to ask Mr. Zhao to help his eldest son, Uncle Wang’s brother, apply for a scholarship in the United States. When Uncle Wang left Taiwan to study in the United States, Wang Shoukang, who had already had a stroke, personally went to the airport to see him off with students’ support. He leaned against the wire fence, spreading his hands and pointing to himself, his lips slowly moving, always maintaining a smile. Uncle Wang actually understood the instructions in his father’s heart: “You must study hard. I’m fine…” This was the last farewell between father and son. It lingered in Uncle Wang’s heart and never disappeared.

On June 19, 1975, after a long illness, Wang Shoukang left forever. Lin Haiyin later described with deep feeling: “The time tunnel brought me back to the small wooden house on Section 3 of Chongqing South Road. When Mr. Fuqing had not yet fallen ill, music from an elderly couple’s instrumental ensemble often came from next door—Mr. Wang’s bamboo flute and Mrs. Wang’s vertical flute, playing ‘High Mountains and Flowing Water.’” What a wonderful scene! Mr. Wang Shoukang’s life was like mountains, rising and falling dramatically, and his adherence to the national language was like flowing water, distant and long.

References:

“Ten Years of Wandering as a Mischievous Child” by Wang Zhengfang, Beijing Publishing Group Beijing October Literature and Arts Publishing House, November 2018

“Jokes as Always, A Youth” by Wang Zhengfang, Beijing Publishing Group Beijing October Literature and Arts Publishing House, June 2020

“Ambitions in All Directions, A Man” by Wang Zhengfang (USA), Beijing Publishing Group Beijing October Literature and Arts Publishing House, January 2023

“Outline History of the National Language Movement” by Li Jinxi, Commercial Press, May 2011

November 3, 2025, in Beijing