Li Jinxi, the Defender of the National Language

Author: Yun Wang

—- Figures in the National Language Movement

(Li Jinxi at home in the 1950s)

The National Language Movement is essentially synonymous with the reform of modern Chinese language and literature, encompassing language, script, and literary style at all levels. Li Jinxi is one of the main leaders of the National Language Movement. At the age of 86, he wrote a couplet that read: “I’ve staked my life, throwing caution to the wind; why worry about praise or criticism, I’m utterly indifferent,” expressing his sentiments towards the National Language Movement. Mr. Li authored over 150 specialized works (with more than 90 published), and wrote more than 570 articles (with over 460 published). His main contributions were focused on the compilation of textbooks and dictionaries, research on Chinese grammar, etc., all revolving around the exploration, adherence, popularization, and development of the National Language. He was a true defender of the National Language.

In 1915, Li Jinxi, who was working at the Ministry of Education, was not content to spend his time copying ancient inscriptions or reading Buddhist scriptures. He began to discuss Sinology, language and script, and the unification of Chinese language and vernacular Chinese with colleagues, including Zhou Shuren (Lu Xun), Chen Maozhi, Lu Ji, and Dong Ruichun, among others. They deeply felt that the people’s wisdom could not keep pace with the republic’s system and sought to use the authority of the highest educational body to push for reform in education, focusing on the issue of script. They wrote articles advocating for “unity of spoken and written language” and “unification of the national language,” and requested the Minister of Education to change the “Department of National Literature” to the “Department of National Language.” Mr. Li wrote in “The Fundamental Problem of Education”: “The majority of the citizens, due to their inability to understand literary meanings, know absolutely nothing about national politics… However, after the restoration of the republic, if we neglect the fundamentals and allow the majority of the citizens to remain illiterate and deaf, then the term ‘public opinion’ will once again be usurped by a minority, and true republican politics will never be achieved. The key lies within the four years of compulsory education, and whether the national script learned during these four years can be applied or not.”

After these articles were published, they were met with staunch opposition from individuals such as Lin Shu and Hu Yujin, who engaged in over a dozen articles of rebuttal with Li Jinxi and Peng Qingpeng, published in the “Beijing Daily.” As a result, more than two hundred letters of support for Li Jinxi’s side came from various provinces, and representatives were sent to promote the establishment of the “National Language Research Society.” Even Hu Shi, who was in the United States, wrote a letter requesting membership.

Although scholars believe that the National Language Movement can be traced back to the late 19th century during the Qing dynasty, the establishment of the “National Language Research Society” was the first time the term “National Language” was formally introduced. It extended Chinese education from written literature to everyday spoken language, making language-led, unified spoken and written new language education the mainstream. By 1920, the membership of the National Language Research Society had reached 12,000 people. With the advent of vernacular Chinese, phonetic alphabets, and new punctuation in magazines like “New Youth” and “New Tide,” the liberation of script unleashed the liberation of thought, heralding the era of the Chinese literary renaissance.

Following the requirements of the “National Language Research Society’s Action Plan,” Li Jinxi actively promoted the establishment of the “Preparatory Committee for the Unification of the National Language” and served as a standing committee member. This organization was under the Ministry of Education, taking over the responsibilities of the previously fallen Unified Pronunciation Committee, adhering to the “Ministry of Education’s duties” to oversee the unification of pronunciation. Its roles included being the highest educational administrative authority to assist and promote, and over its thirty years of existence, it accomplished the following tasks: announced and revised the Phonetic Alphabet; published the “National Pronunciation Dictionary” and the “Revised National Pronunciation Dictionary,” establishing a national standard for Chinese pronunciation for the first time; advanced school system reform, changing the Department of National Literature to the Department of National Language, and promoting vernacular Chinese; established a National Language Dictionary Compilation Office, completing several important dictionaries for language teaching and education; established a system of national language inspection, guidance, and rewards and punishments; successfully tested the National Pronunciation Telegraph; opened training institutes in various places to train professionals in the National Language, and more.

The officially announced Phonetic Alphabet was initially a “recording alphabet” temporarily used by the Unified Pronunciation Committee during the verification of character sounds, created by Zhang Binglin and proposed for use by Ma Yuzao, Zhu Xizu, among others, and was not invented by Li Jinxi. However, Mr. Li spared no effort in promoting the Phonetic Alphabet. Many people found learning the Phonetic Alphabet troublesome and were reluctant to teach it. Mr. Li patiently explained to everyone that knowing the alphabet allows one to read newspapers and books according to the phonetic notation, achieving ‘sound entering the heart clearly,’ which is an extremely efficient method. Unexpectedly, when promoting the use of the Phonetic Alphabet in elementary school textbooks, Shanghai’s publishing industry was the first to protest. Not only booksellers but also national newspapers and public agencies found it materially difficult to adopt phonetic symbols in print due to the increased costs of engraving new typefaces and the resulting increase in printed material values. Mr. Li realized that promotion was not only about advocacy but also about solving practical material problems. He personally drafted horizontal and vertical fonts with phonetic symbols and proposed that the government fund the casting of typefaces. The issue then arose: with tens of thousands of Chinese characters, how many should be made? Therefore, Mr. Li led a group of experts to select 5,787 commonly used characters from over 50,000 through voting, establishing a common character list, which ultimately facilitated the casting of the typefaces.

The process of determining the national pronunciation also faced numerous challenges, most famously the three-year-long “Capital-Nanjing Dispute.” The issue began with the publication of the first edition of the “National Pronunciation Dictionary,” when Zhang Shiyi from the Nanjing Higher Normal School wrote “The Issue of National Language Unification,” advocating for a fundamental overhaul of both the phonetic alphabet and national pronunciation. After much debate, Li Jinxi identified the crux of the problem as being related to tones. He stated in the preface of “The Spectrum of Entering Tones in Beijing Pronunciation” (1923): “Tone is the soul of the pronunciation of characters. Once the tones are in disarray, everything becomes chaotic. Using local accents, the National Language has become a ‘Blue-Green Mandarin,’ neither entirely southern nor northern, sounding bizarre and uncomfortable to everyone.” Later, the entering tones in the national pronunciation were abolished, changing from five tones to four, which essentially resolved the issue. Subsequently, Li Jinxi and seventeen others were appointed to the committee for the “Revised National Pronunciation Dictionary” to redo the standard pronunciation.

Opposing the reading of classics in elementary and middle schools and promoting the teaching of vernacular Chinese was one of the earliest proposals made by Li Jinxi and also faced the greatest resistance. From conservative scholars like Lin Shu and Hu Yujin to officials like Zhang Shizhao who demanded the restoration of classical reading in elementary schools, coupled with warlord conflicts, varying local agendas, and the Nationalist Government being in a precarious state, with the Ministry of Education frequently failing to pay salaries and take action. Within a few years of the National Language’s implementation, the Fengtian Education Bureau prohibited the use of vernacular language and the teaching of the Phonetic Alphabet; Sun Chuanfang, commander of the Southeastern Army, revived rituals and music in pursuit of high culture due to cooperation between the Zhili and Fengtian cliques; the governor of Hubei also ordered the restoration of “ancient academies.” Meanwhile, citizens in Wuxi petitioned against coeducation, and elementary schools in Shandong began to strictly ban vernacular Chinese… The National Language Movement struggled amidst a backdrop of conservatism, warfare, and poverty.

To stay true to their original intentions, Li Jinxi and his colleagues made efforts to promote the announcement of relevant decrees by the Ministry of Education through various proposals, such as the “Amendment to the Primary School National Language Curriculum Outline” (1923), which clarified teaching standards for elementary and middle schools. On the other hand, they worked with colleagues to review and edit related textbooks. Mr. Li excelled at creating teaching materials. While at the “Hongwen Book Compilation Society” in Hunan, he was the first to incorporate ancient vernacular novels like “Journey to the West” into national literature textbooks, a pioneering move that proved successful. During his tenure as the director of the “Book Review Committee” Section A (Liberal Arts) of the Ministry of Education, there was a significant transformation in elementary and middle school textbooks, with the emergence of works such as children’s songs, fairy tales, and folk songs. The “New Teaching Materials: Elementary School National Language Textbooks” compiled by Li Jinxi and his brother Li Jinhuai were particularly well-known. To secure the publishing rights for this series, the Commercial Press specially invited the Li brothers to join them. One of Mr. Li’s most legendary experiences was when he initiated the public burning of primary school classical Chinese textbooks at a joint meeting of normal schools from Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui provinces in Wuxi, which was quite shocking. Looking back on this event in his later years, he felt that his act of “book burning” was a bit too impetuous due to youth. Qian Xuantong once said, “In the sixth year of the Republic of China, two major flags were raised: one was the literary revolution advocated by Hu Shi and Chen Duxiu, and the other was the use of National Language textbooks in elementary schools championed by Li Jinxi and Li Jinhuai.

The compilation office of the “Great Dictionary of Chinese” was under the Preparatory Committee for the Unification of the National Language, co-directed by Li Jinxi and Qian Xuantong. Initially set up at the former Presidential Palace of Zhonghai, its establishment reflected the importance it received at the time. It was China’s first dictionary institution and achieved many miracles. With a small team, it clipped articles from 440 books and newspapers and collected nearly 3.5 million cards within five years, a feat comparable to the “Oxford English Dictionary.” During the compilation process, they applied statistical principles to make the selection and arrangement of words more scientific. Despite wars and government changes, the staff remained committed, completing important dictionaries such as the “National Pronunciation Common Word Collection,” “National Pronunciation Dictionary,” “New Radical Index National Pronunciation Dictionary,” “Revised and Annotated National Pronunciation Common Word Collection,” “National Language Dictionary” (4 volumes), “Enlarged and Annotated New Rhymes of China,” “Cultural Learning Dictionary,” “Homophones Dictionary,” “Chinese Dictionary,” and more. These works became long-standing tools for the standard of the National Language. Meanwhile, the compilation office also produced dozens of “by-products” in the process of collecting and organizing materials, including specialized works and classics on language and script, training a large number of professional dictionary compilation talents in China. In 1937, with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the sudden tension in Beiping, Li Jinxi built a three-story Yulu Pavilion in the northern suburbs of Hengyang, Xiangtan, in preparation for the southward relocation of the Great Dictionary of Chinese compilation office. He mentioned this in his five-character poem “Returning to Xiangtan” — “Planning to move the school to Nanyue, deciding to relocate the office to central Hunan.” It shows how he regarded the work of the compilation office as important as his own affairs.

In the field of linguistics in our country, there is a consensus: “The study of grammar began with ‘Wentong,’ and the study of syntax was established by Elder Li.” Li Jinxi is acclaimed as the “forefather of modern Chinese grammar.” His work, “Newly Written National Language Grammar,” was the first to systematically unveil the intrinsic grammatical rules of vernacular Chinese and was pioneeringly included in the curriculum of the Chinese department at Beijing Normal University, where it was taught in classrooms.

To combat retrogressive thoughts, Li Jinxi and Qian Xuantong organized the publication of “National Language Weekly” in their personal capacity, opposing the “Jiayin” magazine founded by Zhang Shizhao, until their victory. In fact, Mr. Li and Zhang Shizhao were both fellow villagers and good friends, but they argued based on principles over academic issues. In the process of spreading the National Language, Mr. Li organized lecture halls across the country. He not only personally visited various places to inspect the lectures but also taught and recruited instructors himself. Including Mr. Li, a few members invented the National Language Romanization, a brand-new script for the National Language. They led by example in using this script for communication and various occasions and published newspapers and books in this script.

During the war of resistance against Japan, Li Jinxi and Wu Zhihui initiated the establishment of the “National Association for National Language Education,” proposing four fundamental guidelines for National Language education: “unification of the National Language,” “consistency between spoken and written language,” “use of National Phonetic Alphabet to supplement Chinese character teaching,” and “use of local phonetic notations to promote national and border education.” After Beijing Normal University moved to the northwest, aside from teaching, he also oversaw the publication of the Nanzheng edition of “National Language Weekly” and the Lanzhou edition of “National Language Weekly.” In the later stages of the war, Mr. Li founded a National Language special training program in the northwest to train specialized National Language teaching personnel for Taiwan. After the liberation of Taiwan, over 100 graduates from the special training program at Beijing Normal University and others went to Taiwan, becoming the backbone of the promotion and teaching of the National Language there. In 1983, a renowned Taiwanese professor, Liang Rongruo, wrote in a memorial article, praising Teacher Li Jinxi: “He didn’t have the air of only teaching the talented; he considered it an achievement to teach the simple and write simple books. He viewed academia as a skill for serving the masses…” Taiwan erected a bronze statue in honor of Li Jinxi.

Li Jinxi long served as the official spokesperson for the National Language Movement, advocating for the National Language and contending with its opponents. In the 1930s and 1940s, leftists proposed the Latinization of Chinese characters as a goal of the movement, opposing the standardization of the National Language based on Beijing dialect, arguing that it was an attempt to eliminate dialects, a form of linguistic “centralization.” Mr. Li criticized the leftists’ misunderstanding of the National Language Movement, stating that “using the northern dialect as the standard language” and the left’s “letting various dialects gradually merge into a unified language” were not contradictory. The leftist’s proposal was a language “of the public” but “not practical,” utterly outdated. Subsequently, he specifically wrote an article, “The ‘Non’ Unification of the National Language,” which was published in the “Culture and Education” biweekly and “National Language Weekly” in Beiping, simply reaffirming the aims of the National Language Movement Convention, indicating that the “unification of the National Language” was meant for the spiritual unity of the entire nation, while “non-unification of the National Language” aimed at promoting local characteristics. Its essence was “the National Language should be spoken by everyone, but not everyone must speak it.” In response to the left’s objections to vernacular Chinese and their concept of a “mass language,” Mr. Li had Wang Shuda from the dictionary compilation office compile extensive materials on “the masses” and published several articles based on this, showing that the expression of “mass language” was not significantly different from “National Language” or “vernacular,” countering the leftists and defending the status of the National Language.

Li Jinxi, who advocated the middle way, continuously revised his definition of the National Language in response to criticism, hoping to accommodate and meet the diverse understandings and requirements of different groups towards the “National Language” in a flexible and inclusive manner. To address the leftists’ perception of the concept of the National Language as exclusionary, Mr. Li broadly defined it as “all varieties of languages within the territory of our country,” which included ethnic minority languages (Mongolian, Hui, Tibetan) and languages of other countries influenced by Chinese (Korean, Japanese). In 1948, he expanded the definition to encompass “all languages spoken by residents of our country’s territory, including nationals abroad,” considering any language spoken by nationals as part of the National Language. In August 1949, at the “Chinese Character Reform Association,” Li Jinxi emphasized that some people had misunderstood the National Language, limiting the term’s scope to “unification of the National Language.” In fact, just like the national flag, emblem, and anthem, the content of the National Language could change, but its name remained constant. He attempted to maintain the name “National Language” through a pragmatic and flexible approach.

Since the National Language Movement was conducted under the auspices of the Nationalist Government, Li Jinxi was undoubtedly seen as siding with the Kuomintang. When China underwent a change in regime, Mr. Li took the initiative to write to Wu Yuzhang, expressing his willingness to collaborate on creating a new script, setting aside his views on the Latinization of Chinese characters. In reality, what Mr. Li sought to preserve were the two main objectives outlined in the “National Language Movement Declaration” he drafted: “unification of the National Language” and “popularization of the National Language.” However, as political winds shifted, the term “National Language” was eventually replaced by “Putonghua,” and the role of the National Language Movement was diminished in Mainland China. Zhang Xiruo, then Minister of Education, stated that “Putonghua” was the legitimate heir to “Mandarin” and noted that although the National Language Movement had played a certain role in the standardization of Chinese, its achievements were modest. Li Jinxi then receded from the spotlight and became less visible. In reality, he continued to contribute, albeit not from center stage anymore. In 1949, after several students from the Chinese Department of Beijing Normal University studied the history of the Latinization movements at home and abroad, they founded the “New Script Study Society” to explore new scripts. Li Jinxi was invited as the honorary president and supported and affirmed the society’s research direction in his speech at the inaugural meeting. He also arranged for his assistants Xu Shirong, Wang Shuda, Fu Jieshi, and Sun Chongyi to lecture weekly for the society’s members, generating great excitement among them. In 1955, at the National Conference on Script Reform, one of the four phonetic schemes for Chinese characters discussed was personally drafted by Mr. Li. He tirelessly continued his efforts in this work.

In 1958, Zhou Enlai also acknowledged in his report “The Current Tasks of Script Reform” that “the contributions of Qian Xuantong, Li Jinxi, and Zhao Yuanren in creating the ‘National Language Romanization’ cannot be denied.” Those who truly study this history and Chinese linguistics are well aware that today’s Putonghua is still a product of the National Language Movement, and the Pinyin system is essentially a variant of the National Language Romanization. The historical significance of the National Language Movement and the contributions of Li Jinxi and others cannot be erased. As praised during the 110th anniversary of Mr. Li’s birth, his achievements in Chinese language and script are akin to “establishing correct names for a thousand years of work, and opening literacy to thousands of families.”

Li Jinxi became a leading figure in the National Language Movement due to a combination of his family background, education, personal dedication, and the historical context of his time. Born in 1890 in Longtang, Lingjiao Village, Shitanba, Xiaoxia Township, Xiangtan County, Hunan Province, into a family known for its scholarly pursuits, he was the eldest of the “Eight Horses of the Li Family,” all of whom were outstanding talents in the scientific community. Li Jinxi’s father, Mr. Li Song’an, was a local sage passionate about public welfare. He ran a family school at home for his family and neighboring children. After the Xinhai Revolution, Mr. Li was among the first to transform the family school into a modern school, introducing a curriculum that blended Chinese and Western subjects such as arithmetic, physical science, natural history, music, fine arts, and physical education. The family’s Beixiangfang, called “Reciting Fen Tower,” was a library and a gathering place for local literati to discuss, recite poetry, and paint. Thus, Li Jinxi received a modern education from an early age and learned to interact with literary circles.

Diligently studious, he and his father both passed the imperial examinations at the age of 15. Later, aiming for industrial salvation of the country, he studied at the Beijing Railway School’s specialized course. Upon returning to his hometown, he worked as a teacher and editor. During Yuan Shikai’s attempt to become emperor, he and friends took it upon themselves to monitor the National Government and began publishing a newspaper. His groundbreaking work of incorporating vernacular novels like “Journey to the West” into textbooks caught the attention of the Ministry of Education, bringing him into Beijing’s educational circles. Mr. Li held public office in relevant departments of the Ministry of Education for a long time, had good connections, and could leverage administrative power to promote his ideas. As a leader of the National Language Movement, his profound literary skills, persistent spirit, and strong sense of social responsibility were his driving forces. Li’s dedication is evident from his practice of keeping a diary from the age of 12 without interruption, a valuable historical resource now housed in the National Library of China. Although it was difficult for him to exert his influence during the decades of Communist rule, he was preparing a written speech for the Beijing Regional Language Planning Meeting on the day of his death.

Regarding Li Jinxi’s influence at its peak, his parents’ 60th birthday celebration in Beijing in May 1930 stands out. Notable figures like Hu Shi, Zhou Zuoren, Qian Xuantong, Zhao Yuanren, Liu Bannong, Wei Jiangong, Gu Jiegang, Shen Congwen, and Qi Baishi attended, startling the restaurant owner and showing Li Jinxi’s significant influence, as nearly half of Beijing’s university professors were present. Li’s “History Outline of the National Language Movement” meticulously records the process and aims of the movement and promotes its principles. The book was later designated by the Nationalist Government as a training manual for National Language instruction and is considered by later generations as the “official history” of the National Language Movement.

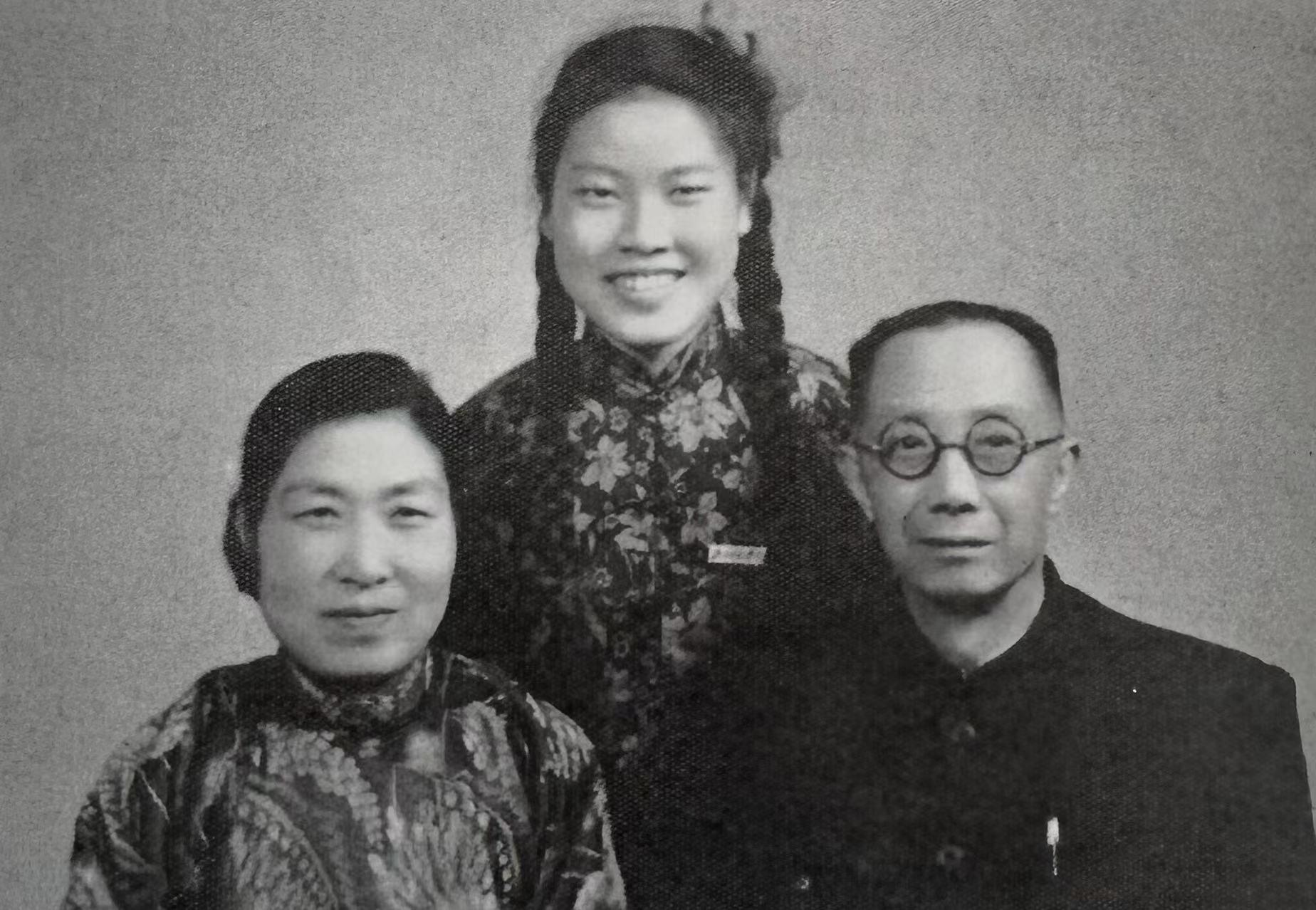

(Li Jinxi with wife He Zhanjiang and youngest daughter Li Zeyu)

References

“History Outline of the National Language Movement” by Li Jinxi

published by the Commercial Press, delves into the detailed history of the National Language Movement, chronicling its development, challenges, and Li’s personal contributions and philosophies regarding language reform and standardization in China.

“Biography of Li Jinxi” by Kang Huayi

published by Hunan People’s Publishing House, offers an in-depth look at Li Jinxi’s life, from his upbringing in a scholarly family to his pivotal role in the National Language Movement, highlighting his personal virtues, academic endeavors, and the socio-political context of his work.

“Voice Enters the Heart” by Wang Dongjie

published by Beijing Normal University Publishing Group, explores the impact of the National Language Movement and Li Jinxi’s significant role in it. This work emphasizes the linguistic, educational, and cultural shifts that resulted from the movement, reflecting on how Li’s efforts helped shape modern Chinese language education.

“Proceedings of the 120th Anniversary of Li Jinxi’s Birth and Seminar on His Academic Thought” by Zhonghua Book Company

compiles research papers and discussions from a seminar dedicated to commemorating Li Jinxi’s 120th birthday. The collection assesses his academic contributions, exploring the lasting influence of his work on Chinese language and literature studies.