The Seal Carving Art of Wei Jiangong (Aliases: Qianren, Tianxing, and Shangui)

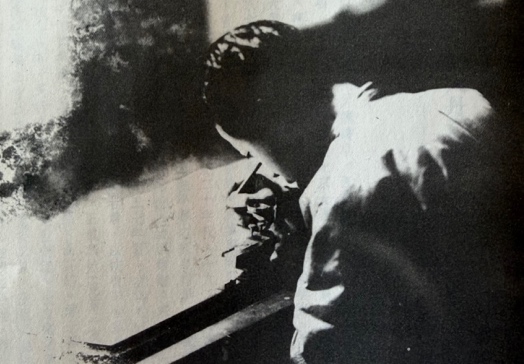

Wei Jiangong Carving a Seal (1928)

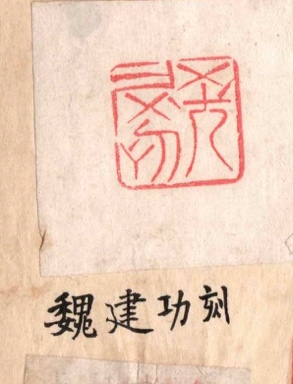

My grandfather had a seal that I, as a child, thought was some kind of celestial script, but I knew he cherished it deeply. Decades passed, and while browsing through books left by my great-grandfather, a small slip of paper caught my eye. On it was the impression of that strange seal, with a small note beside it: “Carved by Wei Jiangong” (Figure 12). I knew my grandfather had worked with Wei Jiangong at the National Dictionary Compilation Bureau, but I never knew he was a renowned seal carving artist in his own right.

Wei Jiangong began carving seals in the 1920s. “Tianxing” was his courtesy name, and “Shangui” (Mountain Ghost) was his pseudonym; he often used them together when signing his artistic works. In 1928, as the Northern Expedition approached Beijing and the situation grew chaotic, several mentors from the Peking University Research Institute—including Shen Jianshi, Chen Yuan, Ma Heng, Liu Bannong, and Xu Senyu—founded the Cultural Relics Maintenance Committee to protect Beijing’s historical treasures. Younger teachers like Tai Jingnong, Chang Weijun, Zhuang Shangyan, and Wei Jiangong also actively participated. These mentors, mostly experts in paleography and epigraphy, often discussed Han and Wei stele rubbings and ancient seals from the Qin and Han periods. The younger scholars’ interest grew, and at Zhuang Shangyan’s suggestion, they founded the “Yuantai Seal Society.” Its members included Zhuang Shangyan, Tai Jingnong, Chang Weijun, Wei Jiangong, and Jin Manshu, with Wang Fu’an and Ma Heng serving as advisors. “Yuantai” was named by Ma Heng after the historical name of the Circular City (Tuancheng) in Beihai, where they were based. To demonstrate, Ma Heng carved a “Yuantai Seal Society” seal in the Qin style on the spot, followed by Wang Fu’an, who also gifted the group one of his original seal albums for study. Interestingly, while members like Tai, Chang, and Wei threw themselves into the practice, the founder Zhuang Shangyan, despite his profound knowledge and passion for collecting, never actually picked up the carving knife himself.

Wei Jiangong spent over twenty years mastering the craft, integrating styles from oracle bones, bronze inscriptions, Qin seal script, and Han clerical script, while drawing inspiration from the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties to create works of profound antiquity. Carving as a scholar, his subjects were mostly luminaries of the cultural and academic worlds. These seals were born of shared interests, deep friendships, or the bond between teacher and student, some even carrying poignant stories that became legends in literary circles.

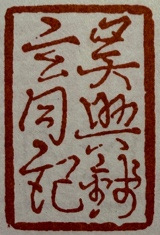

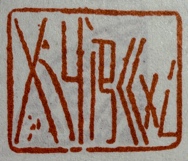

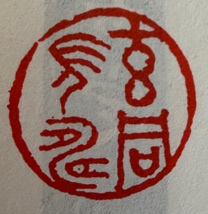

Qian Xuantong and Wei Jiangong shared a mentor-student bond that was both intellectual and fraternal. During their time at Peking University, Qian loved visiting Wei’s home for a meal and a chat, sometimes even staying the night. In the summer of 1937, as Japanese troops entered Beiping, Peking University moved south. Qian, unable to travel due to his health, indignantly prepared to resume his revolutionary name “Qian Xia” to symbolize his refusal to coexist with the invaders. On November 2, Qian wrote in his diary: “Tianxing came at ten; he plans to depart for Yunnan on the 20th… He wanted me to inscribe a scroll of his grandfather’s letters, and I wanted to ask him to carve a ‘Qian Xia Xuantong’ seal. He left at one.” On November 10, Qian bought an Qingshi stone for two yuan at Tonggutang, intending to ask Tianxing to carve it. On November 11, he noted: “Tianxing sent the seal he carved for me today… The seal is excellent (Figure 1)… the characters ‘Qian Xia’ are a riddle for ‘Jue Miao’ (Exquisite) [Note 1].” This seal, carved in regular script with a dignified and upright air, reflected the character of the man. Little did they know this departure would be their final farewell. This seal impression was later placed on the first page of Wei Jiangong’s seal album, Duhoulaitang Yincun.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

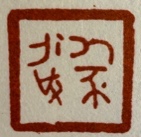

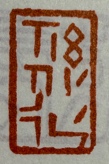

Qian Xuantong was extremely particular about seals. In 1928, he bought a black Shoushan stone and asked Li Jinxi to request the master Qi Baishi to carve “Yigu Xuantong” in a style that “didn’t follow established rules.” Later, however, Qi Baishi stopped taking commissions. Fortunately, Qian found that his student Wei Jiangong had excelled in the art. In Jan 1932, he wrote: “Jiangong showed me his seals (using phonetic symbols); they are getting better and better, in the style of Qi Baishi, with excellent knife work.” (Figures 2-4 are seals carved by Wei for Qian).

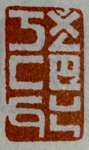

At the time, as a standing committee member of the Preparatory Committee for the Unification of the National Language, promoting the National Language and Zhuyin Fuhao (phonetic symbols) was Wei’s primary duty. He innovatively created seals using these phonetic symbols and published them in the National Language Weekly as puzzles to engage and educate readers. Some seals were even based on the ancient scripts from which the phonetic symbols were derived. For example, he used ancient forms of “Bao, Dao, Zhi, Hai, You” to spell “Bai Dizhou” (Figure 5). When the answer was revealed, it was humorously described as a “twisting riddle.” In fact, if readers knew that the symbols “ㄅ, ㄉ, ㄓ, ㄞ, ㄆ” were stylized versions of those five ancient characters, the riddle was easy to solve. The linguist Luo Shentian recognized it immediately and encouraged his daughter, Luo Kunyi, to enter the contest, winning her a phonetic seal carved by Wei (Figure 6).

Figure 5, Bai Dizhou

Figure 6, Luo Kunyi

Wei’s innovation was unprecedented, and his exquisite skill earned him immense respect among his colleagues in the National Language Movement. They considered it an honor to own a seal from “Tianxing Shangui,” and my grandfather cherished his as a treasure. Each work was meticulously designed, brilliant and fresh. Since there was no traditional standard for these phonetic symbols in seal carving, their asymmetrical structures were challenging to adapt, making Wei’s success all the more remarkable. (Figures 7-15 are phonetic seals carved for his colleagues).

Fig 7, Yigu Xuantong

Fig 8, Yigu Xuantong

Fig 9, Li Jinxi

Fig 10, Wang Yi'an

Fig 11, Wei Jiangong

Fig 12, Wang Shuda

Fig 13, Xiao Dichen

Fig 14, Kong Fanjun

Fig 15, Qi Tiehen

In his design and layout, Wei Jiangong was a traditionalist who wasn’t bound by tradition, an innovator who didn’t invent without basis. Most admirably, he could capture the personality of the seal-owner, making each small mark a reflection of the person. Look at the seal he carved for Zhou Zuoren (Figure 16): the character “Zhou” resembles a shield placed on a stone, while others look like figures sitting or standing, or objects like tables and chairs—lively and dynamic. It fits Zhou’s status as a scholar while also hinting at his love for hosting and lively company. The seal for Liu Fu (Figure 17) is rough and minimalist, with a bold ancient charm that perfectly reflects the unbridled personality of Liu Bannong. Cai Yuanpei’s seal (Figure 18) is more formal, with its fine layout resembling the window lattices of Jiangnan, matching his status as an official from the river towns.

Fig 16, Zhou Zuoren

Fig 17, Liu Fu

Fig 18, Cai Yuanpei

Wei Jiangong was not a professional seal carver; his work carried the scholarly refinement and artistic freedom of a man of letters. He didn’t strive for mechanical precision but created unique works of art. Traditionally, carvers are very particular about stones; the famous Wu Changshuo had a seal made of precious Tianhuang stone, which is said to be worth ten times its weight in gold. Wei, however, innovatively used cheap white rattan canes (vines) as material, creating seals from cross-sections that revealed fascinating grain patterns.

In early 1938, Wei moved to Kunming with Peking University and taught at the Southwestern Associated University (Lianda) in Mengzi. The campus was alive with literary activities—night schools, poetry societies, and wall newspapers. In this atmosphere, Wei began carving inscriptions into walking sticks. He carved a stick for Chen Yinque with the inscription: “The staff of Master Chen, to correct the wayward.” [Note 2] Chen, who was blind in his later years, was never without this stick and even wrote poetry about it. He also carved sticks for Zheng Yisheng, one inscribed “Commanding with Certainty” and another “Use it when needed, hide it when not.”

The rattan used was white rattan from Vietnam, about an inch in diameter. Inspired by Zheng, Wei began cutting sections of rattan to carve seals, reviving his old passion. He was proud of this innovation, saying, “There are thousands of materials for seals in this world; as long as one captures the soul of the art, why must it be cinnabar or Tianhuang stone?” From then on, he frequently carved rattan seals for friends, producing nearly eighty in a year, later collected in his album Why Need Gold and Jade. Among them were two seals for his teacher Qian Xuantong, inscribed “Qian Xia” and “May Xuantong Live Long” (Figures 19, 20), with a heartfelt dedication expressing his pupil’s devotion. When he left Beijing, he had not yet finished the L-shaped seal Qian Xuantong had requested; this was his way of settling that old debt. This was also recorded in Qian’s diary on September 28, 1938.

Fig 19, Qian Xia

Fig 20, Long Life to Xuantong

On July 7, 1939, the second anniversary of the War of Resistance, Lianda professors held a calligraphy auction. Wei’s rattan seals were a massive success. He originally planned to carve 100 but eventually carved 117, donating all proceeds to the war effort. He inscribed “To while away the days without shame before heaven” on the first prints as a memento. After the victory, Wei was tasked with promoting the National Language in Taiwan. In 1946, while back in Beiping, he showed his Auction Rattan Seal Album to friends for inscriptions.

Shen Jianshi gifted him a poem reflecting on their time apart during the war. Shen was also Wei’s teacher and had remained in Beiping during the occupation, constantly worried about rumors that Wei had been injured or killed in the south. Zhang Boju also wrote two poems, one praising the rattan seals for carrying the “mist and smoke” of distant rivers into the scholar’s studio, and another reflecting poignantly on the tragedies of the war and the internal strife that followed.

An expert in phonology, Wei began teaching the History of the Evolution of Chinese Character Forms at Lianda in 1938. He applied his linguistic interest to seal carving, drawing from oracle bones, bronze scripts, and various calligraphic styles with ease. For example, in Sun Xu’s seal (Figure 21), the character “Sun” resembles a child catching a fish; in Xia Jingnong’s (Figure 22), “Xia” looks like a soldier saluting; the seal for Wu Bifei (Figure 23) compresses the top and elongates the bottom to symbolize deep roots and lush leaves; and Cai Jingping’s seal (Figure 24) features the character “Jing” as two people joining hands to reach the finish line, representing “fair competition.” Even Bing Xin spoke fondly of his work, mentioning that she had “righteously bought” a rattan seal (Figure 25) and always used it when asked for her calligraphy. The “Xin” in her seal opens like a flower. Zhou Qiming’s (Zhou Zuoren) seal (Figure 26) uses pictographs to create a serene scene, while Kawashima’s (Zhang Mao-chen) seal (Figure 27) is a purely visual masterpiece.

Fig 21, Sun Xu

Fig 22, Xia Jingnong

Fig 23, Wu Bifei

Fig 24, Cai Jingping

Fig 25, Bing Xin

Fig 26, Zhou Qiming

Fig 27, Kawashima

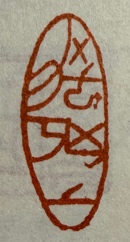

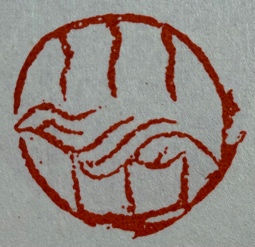

Wei Jiangong also carved seals for his family, infusing each with deep understanding and love. His wife Wang Bishu’s seal (Figure 28) is half delicate and graceful in red, and half solid and profound in white. The seals for his sons, Wei Nai and Wei Zhi (Figures 29, 30), are different in style, perhaps reflecting their distinct personalities. But his most iconic work remains the “Shangui” (Mountain Ghost) seal (Figure 31). Inspired by Qu Yuan’s “Nine Songs,” the Mountain Ghost represents a fusion of refined isolation and unbridled freedom. In this seal, “Shan” (Mountain) sits high, while “Gui” (Ghost) stands upright, creating a powerful composition reminiscent of the white space in classical Chinese painting.

Fig 28, Wang Bishu

Fig 29, Wei Nai

Fig 30, Wei Zhi

Fig 31, Shangui

Wei Jiangong passed away in 1980, leaving behind three major albums containing 458 seal impressions from a twenty-year period (1928-1949). Among the 200 identified owners of these seals, over 90 were scholars and experts teaching at universities worldwide. A native of Jiangsu who made his life in Beijing, Wei loved wandering the bookstores and antique shops of Liulichang, where he became close friends with Chen Jichuan, the owner of Laixunge. Chen’s son later helped Wei’s son publish Impressions of Tianxing Shangui, a testament to the enduring respect and affection among scholars. Wei Jiangong, the “Mountain Ghost,” truly earned such high esteem from his peers.

Note 1 “Huang Juan You Fu” (Yellow Silk and Young Woman) is a famous ancient Chinese riddle source from the Cao E Stele. “Huang Juan” (Yellow Silk) translates to “colored silk” (色絲), which forms the character “Jue” (絕, Absolute). “You Fu” (Young Woman) translates to “young female” (少女), which forms the character “Miao” (好/妙, Exquisite/Wonderful). Thus, the answer is “Jue Miao” (Exquisite).

Note 2 “Chen Jun zhi Ce”: “Ce” here means walking stick or staff. The inscription refers to a righteous path.

Note 3 “Xiqjang” (Striving within the walls): A metaphor for internal or family strife, from the Book of Songs.

Note 4 “Gantang” (Sweet Pear Tree): A metaphor for the benevolent rule of an official, from the Book of Songs.

References: Impressions of Tianxing Shangui, China Bookstore (August 2001) The Diary of Qian Xuantong (Edited Version), Chief Editor Yang Tianshi, Peking University Press (August 2014)

January 27, 2026, in Beijing