The Affinity Between the Compilation Office of the Great Chinese Dictionary and Zhongnanhai

Author: Yun Wang

When chatting with my aunts, they often mention their childhood experiences of going to Zhongnanhai. It turns out that their father, my grandfather Wang Shuda, worked at the China Dictionary Compilation Office (hereinafter referred to as the “Compilation Office”), which used to be located in Zhonghai. As a result, their father frequently took the children to play in Zhongnanhai. My eldest aunt, due to her beautiful handwriting, even worked as a copyist at the Compilation Office in Zhonghai alongside her grandfather. How incredible is that! To most Chinese people, Zhongnanhai seems like a forbidden area, yet it turns out it once served as a beloved destination for Beijing residents. Moreover, the Compilation Office had a twenty-year connection with Zhonghai.

For Beijingers, 1928 was an unusual year. Warlord Zhang Zuolin was killed on his way back to the Northeast, and Warlord Yan Xishan was about to take over. Although the presidential palace had changed hands frequently since the Republic of China was established, this time was different: Beijing was renamed Beiping and, like Tianjin, became part of Zhili Province. The national flag was changed to the Blue Sky with a White Sun flag, marking a significant change. The Nationalist Government moved to Nanjing, with military affairs in Beiping taken over by Yan Xishan and civil administration by the Nationalist Government’s War Area Administration Committee (referred to as the “War Committee”) led by Jiang Zuobin. During the transitional period, public order in Beijing was temporarily maintained by the “Charity Association,” formed by local elders and gentry, led by Wang Shizhen.

Zhongnanhai, known as “The Three Seas of the Western Garden” during the Qing Dynasty, was a royal garden. After the establishment of the Republic of China, Yuan Shikai transformed Juren Hall in Zhonghai into the presidential office. For the next twenty-odd years, it served as the office and residence of the presidents and premiers of the Beiyang Government. On June 3, 1928, Zhang Zuolin left Beijing, and on June 13, the War Committee took over Zhongnanhai.

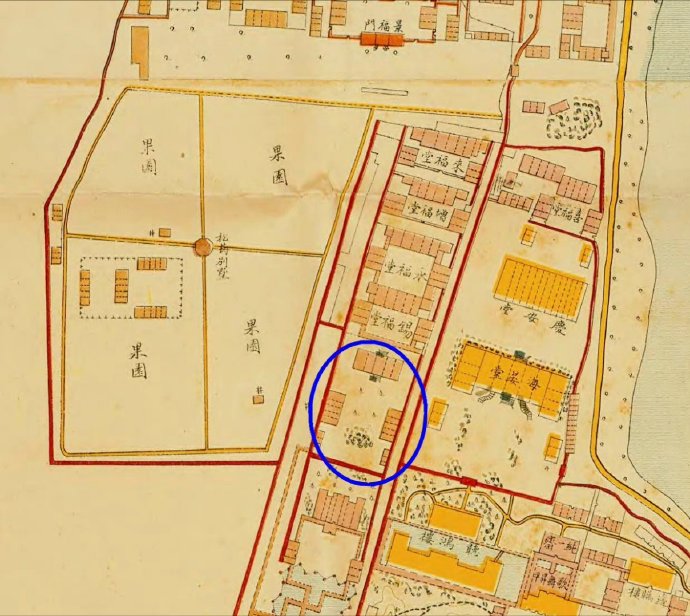

At this time, the Mandarin Movement was in full swing. The plan to compile the Great Chinese Dictionary, closely related to the Mandarin Movement, had been initiated as early as 1919. The Compilation Office was established in 1923, and it wasn’t until 1927 that Qian Xuantong, Li Jinxi, and Wu Zhihui applied for a grant from the China Cultural Fund Board. The Compilation Office was formally established in 1928, and the change of the Nationalist Government presented a turning point for the office. Regarding the office location, the original suggestion was to place it in the former Ministry of Education building, as the Preparatory Committee for the Unification of the National Language (hereinafter referred to as the “National Language Committee”), the superior body of the Compilation Office, was already working there, and the Ministry of Education’s relocation had left many vacant rooms. However, Qian Xuantong had his eyes set on Zhonghai. At that time, the National Beiping Library had been granted long-term use of Juren Hall, and the Compilation Office, tasked with the comprehensive inventory of Chinese characters, should be established alongside it. Consequently, Qian Xuantong and Li Jinxi, the two chief directors, leveraged their personal and governmental connections, and the War Committee ultimately approved the allocation of the four western rooms of Juren Hall for the Compilation Office.

The location of the four western rooms of Juren Hall was originally the Yiluan Hall in Zhongnanhai. Yiluan Hall was Empress Dowager Cixi’s winter palace, which was burned down during the invasion of the Eight-Nation Alliance. After being rebuilt, it was renamed Haiyan Hall. During the Republic of China, Yuan Shikai renamed Haiyan Hall to Juren Hall and proclaimed himself emperor there. The rebuilt Yiluan Hall was also renamed Huairen Hall by Yuan Shikai, and the four western rooms were actually located to the west of Huairen

(Picture Two: Entrance to the Four Western Rooms.)

(Picture Three: Floor plan of Juren Hall and the Four Western Rooms.)

Although approval was granted, the move of the Compilation Office to the Four Western Rooms was fraught with difficulties. The day before the handover, Qian Xuantong and Li Jinxi went together to file a complaint with Yang Shaojiong, the person in charge, reporting that the deputy officer Huang Boduo was “unpleasant and rude” and had taken things at will when inspecting the rooms. Yang Shaojiong, appearing helpless, responded that if things were missing, they would find a way to replace them, indicating that their influence had limited effect. It’s no wonder, given the complexity of interpersonal relationships within the transitioning government departments.

On the day of the handover, the Compilation Office took it very seriously, with the six main personnel—Qian Xuantong, Li Jinxi, Wang Yi, Bai Dizhou, Zhang Weiyu, and Wang Zongjian—arriving punctually at 2 PM. Huang Boduo, who had prior arrangements, did not show up and delegated the task to someone even more unpleasant. This person demanded an official letter from the office and insisted on strict adherence to formal procedures. Qian Xuantong, known for his fiery temper, sought out Yang Shaojiong but was unable to find him, thus choosing to ignore the situation. Wang Yi had to rush back to the National Language Committee office at the old Ministry of Education to retrieve the official letter, and by the time he returned, it was already 4 PM. During the initial handover, the key to Xifutang could not be found, so they started with Yongfutang. The official first ordered a clean chair, then requested a brush pen, rejecting a pencil handed to him and insisting on a brush pen. Fortunately, the Compilation Office had brought one, avoiding further delays. The official slowly wrote the handover list while asking, “Do you want gun racks?” The Compilation Office had no use for such items, but essential items like iron bed frames could not be left behind. In short, patience was necessary for the handover.

The next afternoon, the handover of Xifutang, Yongfutang, and Zengfutang was completed, but the official suddenly claimed that the Four Western Rooms included Laifutang but not Yiyuan. This angered the Compilation Office staff, leading Qian Xuantong and Li Jinxi to seek out Yang Shaojiong again. Yang Shaojiong was also furious, calling the deputies “bastards and robbers.” He sent a letter to the War Committee stating that the Four Western Rooms included Yiyuan. With the letter in hand, the deputy had no argument but claimed that the records had not been completed, delaying the handover.

Unexpectedly, another issue arose. When Mr. Lei Shoumian, who was drawing a map for the library, came to map the area, he informed them that the small houses on the west side of the Four Western Rooms, along with the outer walls and Su Chan and Wan Fu gates, belonged to the library, requiring discussion for division. The Compilation Office hoped these areas would be shared, but it was unlikely the library would agree. The team began to consider how to navigate the situation. Wang Yi, however, voiced strong objections, dismissing the library’s map as “nonsense” and suggesting it be ignored, sparking a debate that ended with one side falling silent. That evening, Qian Xuantong sought out Chen Maozhi for mediation, and Chen Maozhi indicated that there should be no significant issues from the library’s side.

After 11 AM on the third day, the deputy officer, reportedly surnamed Huang, finally appeared, and Yiyuan was handed over. Li Jinxi had other ideas about the division with the library; he even wanted the library to open Juren Hall to the Compilation Office and went to negotiate with Ma Youyu. Ma Youyu agreed but suggested that the Compilation Office give up Zengfutang to the library, allowing the library to have direct access through the Su Chan Gate, making the shared use of Su Chan Gate a non-issue. Qian Xuantong, Li Jinxi, and Bai Dizhou all agreed with this proposal, and Wang Yi tacitly consented. They entrusted Ma Youyu to communicate with the library. Later, Wang Yi had an argument with Ma Youyu over this because Wang Yi still believed that the map drawn by the library was nonsense. In the following days, everyone worked separately with both the Compilation Office and the library staff, and once there were no obstacles, Li Jinxi drafted an official letter to the library.

Only two weeks after the handover was completed, Zhongnanhai was to be partially opened to the public for half a month. The Office of Government Affairs, without consulting the Compilation Office, included Yiyuan in the open area. Qian Xuantong, Li Jinxi, and others had to coordinate with officials again and later learned that it was again the doing of the officer surnamed Huang. After Zhongnanhai’s trial opening, the library sold Tianjin buns and delicious wontons outside Juren Hall, truly becoming more accessible to the people.

(Picture Four: The main gate of the Compilation Office at the Four Western Rooms.)

(Picture Five: The first gate of the Compilation Office at the Four Western Rooms.)

In April 1929, the Beiping municipal government established the “Temporary Committee for the Renovation of Zhongnanhai Park” (hereinafter referred to as the “Temporary Committee”) to handle matters related to Zhongnanhai. In May, the “Temporary Committee” named it “San Hai Park” and officially opened it to the public, marking the only period when Zhongnanhai was accessible to the common people. In December 1930, the park’s name was changed to “Zhongnanhai Park,” with a horizontal plaque inscribed with “Zhongnanhai Park” in the Wei style by Zhang Hairuo, an old official of the Qing Dynasty, hanging inside the lower gate of Xinhuamen.

According to Mr. Han Enzhong of the First Historical Archives of China, more than 100 rooms in the park, including Juren Hall, Xifutang, Huanle Zhuang, Zengfutang, Laifutang, and Guoyuan, had been borrowed long-term by the National Beiping Library Preparatory Committee since the autumn of 1928. It wasn’t until after the “Temporary Committee” was established in 1929 that, following several negotiations, they gradually moved out due to the completion of the library’s new building on Wenjin Street. Xifutang, Yongfutang, and Yiyuan in the park were used by the Compilation Office of the Great Chinese Dictionary. From this information, it can be inferred that despite their efforts, the Compilation Office did not manage to occupy all the properties in the Four Western Rooms. In September 1929, the National Beiping Research Institute was established, with its headquarters and the office of the Historical Research Society also temporarily located in the Four Western Rooms, likely in the area vacated by the library.

The Compilation Office remained in the Four Western Rooms for twenty years, repeatedly facing eviction threats, which they managed to avoid through their connections. During the Japanese puppet regime, Li Jinxi, the chief director, left Beiping, and Qian Xuantong, suffering from illness, stayed home. The Compilation Office lost its financial support, with only a few, such as Wang Yi, struggling to maintain it. Later, the puppet government set up its office in Juren Hall, and Beiping once again became Beijing. The puppet government planned to requisition the Four Western Rooms for compiling new textbooks. The persistent Qian Xuantong, finding it difficult to access Zhonghai, considered giving up. Not long after, Qian Xuantong fell ill and died shortly after being trapped in his office in Zhonghai during a lockdown.

Wang Yi and Wang Shuda were among the last to hold on. Because Wang Yi took up a position with the puppet regime, they managed to self-fund and complete the compilation and publication of the eight-volume “Mandarin Dictionary.” Later, the books of the Compilation Office were moved to the homes of Wang Shuda and others for safekeeping, indicating they were prepared to completely abandon the office. Unfortunately, the “Mandarin Dictionary,” completed during the difficult and painful occupation period, bore the shame of including some Japanese words. After the victory in the War of Resistance, Li Jinxi returned to Beiping, and the Compilation Office became part of the reestablished Beiping Normal University, with Li Jinxi approved to live in the backyard of the Compilation Office in the Four Western Rooms. It was here, amidst the roaring artillery of the People’s Liberation Army’s siege, that Li Jinxi completed the preface to the four-volume “Mandarin Dictionary.” The official publication of the “Mandarin Dictionary” was the most important achievement of the Compilation Office’s work, becoming the standard for modern Chinese on both sides of the Taiwan Strait and the basis for all subsequent dictionaries. Remarkably, the publication of this book also marked the end of the Compilation Office’s work in Zhonghai.

Working in Zhongnanhai was a unique privilege. Besides the office space, unmarried employees of the Compilation Office also lived there until they got married and started their own families. Sun Zishu not only lived in the Four Western Rooms but also worked part-time at the library, making commuting extremely convenient. Of course, the beautiful scenery of Zhongnanhai was the best benefit for everyone. Qian Xuantong visited Zhonghai almost daily. Whether it was discussing philological scholarship, teaching plans, or entertaining friends and officials, Zhonghai became his place for work and socializing. He enjoyed strolling around Zhongnanhai, sometimes alone and sometimes with friends. He even turned Xifutang into his “writing debt” spot, where he wrote plaques for the Beiping Library, the Affiliated High School of Beijing Normal University, and more. He also wrote tombstones for Liu Bannong and countless elegiac couplets.

When Li Jinxi lived in the Four Western Rooms, his stepdaughter, Zhong Hong, recalled in her autobiography: “When the rickshaw stopped in front of the Compilation Office of the Great Chinese Dictionary, I was home. What a serene place! Entering through the west gate of Zhongnanhai, there was a curved fence on the right, a middle school on the left, and to the east of the middle school was the City Council. Walking a bit further, you reached the Compilation Office of the Great Chinese Dictionary. The building was named Huairen Hall, with high steps and big red lacquered doors. To the east of the Compilation Office was a large gate through which you could see the rippling waters of Zhonghai in the distance.” Li Jinxi often stood on the west bank of Zhonghai, gazing at the lake. To the east of Zhonghai was a wooden bridge named Centipede Bridge, a spot where late Qing Dynasty scholars awaited their exam results. It had become a place for young men and women to meet and fish. In his 1937 poem “Eight Summer Interests,” he wrote: “The fragrance of lotus flowers by Zhonghai’s waters, from where I gaze at the jade island that is Penghu. By Centipede Bridge, people fish, and before Ao Dongfang, a dog steals books. I still remember listening to the cranes at the Temple of Heaven, always watching the ducks float by the White Pagoda. Where are my boatmates now? In the mirror, eyebrows are seen, but below, only skulls remain!”

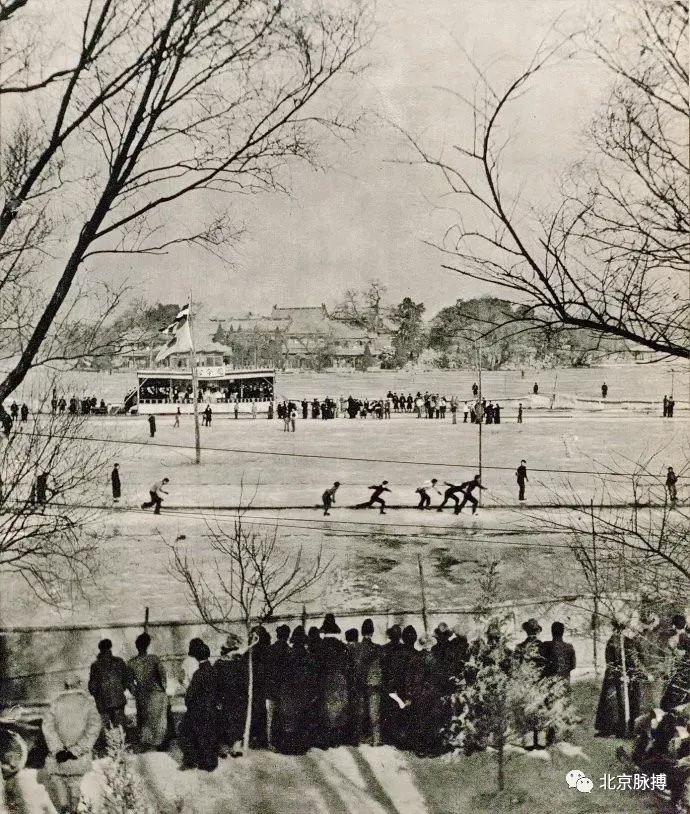

My father often reminisced about the joy and mystery of going ice skating in Zhongnanhai with his father, Wang Shuda, similar to Zhong Hong’s experience. Wang Shuda was a student of Qian Xuantong and Li Jinxi. He graduated from the Chinese Department of Beijing Normal University in 1928 and started working at the Compilation Office as an assistant compiler from its inception until it merged with the Institute of Linguistics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. In 1929, he took his wife and their first child to Jinggu in Zhongnanhai to take their first family photo (Picture Six). He witnessed the obscure history of the Compilation Office in Zhonghai: 2.5 million index cards, numerous manuscripts and materials, and negotiations with government officials and other personnel for office space and funding. He saw Beiping become Beijing, Beijing revert to Beiping, and then Beiping become Beijing again. He saw the passing of scholars like Liu Bannong, Bai Dizhou, Qian Xuantong, and Ma Youyu. Despite everything, I believe he and everyone else deeply cherished working in this mysterious royal garden during its brief period open to the public.

(“Picture Six: Wang Shuda’s family photo in Jinggu, 1929.”)

(“Picture Seven: The Nanhai Ice Skating Rink during the public period.”)

May 27, 2024, Beijing

References:

“1928: The Transition of Beijing and Tianjin, The Kuomintang Regime and Beiping Society” by Wang Jianwei

“The Diary of Qian Xuantong” (Edited) by Yang Tianshi, Peking University Press

“A Critical Biography of Qian Xuantong” by Wu Rui, Baihuazhou Literature and Art Publishing House

“Wind and Rain on the Half-branch Lotus” by Zhong Hong, Hualing Publishing House

“Overview of the Compilation Office of the Great Chinese Dictionary” by the Compilation Office of the Great Chinese Dictionary