Tracing Zhongshan Park

Author: Yun Wang

When I was a child, I often followed the adults to Zhongshan Park. Sometimes, a whole big family would go, which was the happiest time for the children. Not only could we look at the flowers and trees and play around, but we could also spend some time in the amusement park while the adults stood by chatting and accompanying us. Of course, another important part of the park visit was taking group photos in various combinations of all the participants. Looking back today, these photos are extremely precious, and the tradition of the whole family visiting the park together has long ceased. As I began researching my grandfather, I gradually discovered that visiting the park was their way of life. For those who worked at the China Dictionary Compilation Office in Zhonghai at that time, Zhongshan Park was simply a part of their lives. So, I tried to retrace the path they once walked.

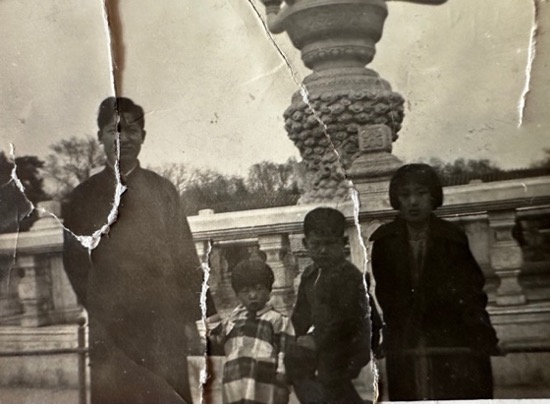

(In the late 1930s, Wang Shuda and his three children took a photo in front of the stone lantern at the “Justice Triumphs” archway.)

(In 1974, the entire family in Beijing celebrated Wang Shuda’s 70th birthday (Wang Shuda is the third from the right in the back row))

Standing outside the west gate of Zhongshan Park on Nanchang Street and looking north, not far away is the West Garden Gate of Zhongnanhai. I imagine my grandfather and his companions exiting the West Garden Gate of Zhongnanhai and entering the west gate of Zhongshan Park. However, when I got my hands on a map from the Republic of China era, I realized that Zhongshan Park didn’t even have a west gate at that time.

Zhongshan Park was originally the altar for the gods of soil and grain during the Ming and Qing dynasties, where emperors performed sacrifices. Therefore, it only had an east gate connected to the Forbidden City. In 1913, Zhu Qiqian, then Minister of Communications of the Republic of China, saw the expansive grounds, ancient cypress trees, towering halls, and the river at the rear and the main road at the front outside the Sheji Altar while performing his duties outside the Meridian Gate of the Forbidden City. He proposed converting it into a park, which the government approved. Due to the lack of funds in the Republican government, he initiated fundraising, donating 1,000 silver dollars himself. Subsequently, 96 Republican figures, including Duan Qirui, Cao Rulin, Gu Weijun, Wang Kemin, Xiong Xiling, and Yong Tao, donated a total of over 50,000 silver dollars in two rounds, covering the park’s establishment costs. On October 10, 1914, the park officially opened to the public on National Day, named Central Park. Later, in 1928, it was renamed Zhongshan Park in memory of Sun Yat-sen. For convenience, a south gate was opened on the southern edge of the Imperial City when the park first opened. In 1915, a large wooden bridge was built over Tongzi River in the north, creating the north gate. Zhongshan Park was actually China’s first modern public garden in the true sense.

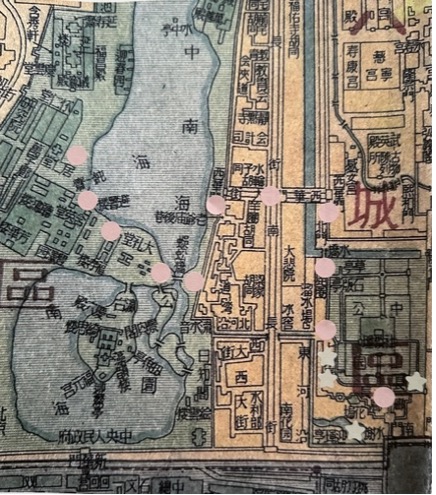

Uncovering this history, I was finally able to trace the steps of my predecessors on the old map. They started from the Xisi Compound of Juren Hall, traveled along the west and south banks of Zhonghai, crossed the Centipede Bridge, and then along the east bank of Zhonghai to the West Garden Gate. Exiting the West Garden Gate, they reached Xihuamen Street, crossed Nanchang Street to the east, followed the east bank of Tongzi River, and crossed the newly built wooden bridge over Tongzi River to enter Zhongshan Park.

(The pink dots indicate the route from Xisi Compound of Zhonghai into the park; the star mark on the east side of the park represents Laijinyuxuan, the star mark on the south side represents Shuixie and Siyixuan, and the star marks on the west side indicate the locations of Chunminguan, Changmeixuan, and Bosixin.)

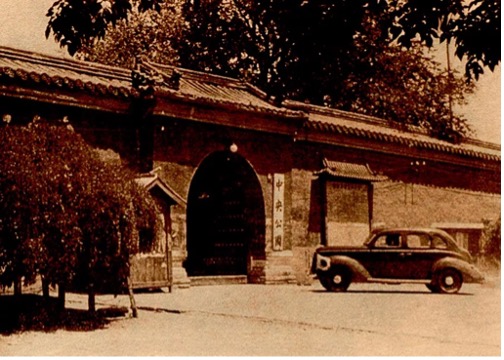

(The main gate of Central Park at the time of its initial opening.)

In early summer, Zhongshan Park is exceptionally tranquil. As soon as I enter the park, I am surrounded by the earthy scent of the garden after watering. The ancient trees remain towering and majestic, while the flower beds, filled with lush green grass interspersed with various colorful flowers, form beautiful patterns that are exceptionally vibrant. With all the noise faded away, there is only the crisp sound of birds, sometimes high, sometimes low, sometimes sharp, sometimes soft, melodious and pleasant, making one feel instantly at ease.

It is said that the park houses over a thousand ancient cypresses, ancient locust trees, elms, apricot trees, pines, cypresses, locust trees, willows, and a large variety of flowers, including peonies, peony flowers, night-blooming cereus, lilacs, lotuses, plum blossoms, peach blossoms, crabapples, roses, yellow roses, Prunus triloba, orchids, trumpet flowers, morning glory flowers, Viburnum plicatum, green apricots, cherry blossoms, and more. Among them, peonies and peony flowers are the most numerous, making them a unique feature of Zhongshan Park. The park is not large, yet it is said that every ten steps present a different view.

The most spectacular feature is the “Defend Peace” archway. In 1903, at the west entrance of Dongzongbu Hutong, spanning Dongdan North Street, the Ketteler Monument was built to commemorate the German envoy Ketteler, who was killed at this site. In 1918, after the end of World War I, the Chinese government, as a victorious nation, dismantled the Ketteler Monument and transported the stone materials to Zhongshan Park. The archway was rebuilt and inscribed with the words “Justice Triumphs,” hence it was called the “Justice Triumphs” archway. In 1925, Zhu Qiqian wrote to Puyi’s Imperial Household Department to apply for the use of some destroyed artifacts from the Old Summer Palace, which was approved. A copper dew basin from the Old Summer Palace was converted into a stone lantern and placed in front of the “Justice Triumphs” archway.

In 1952, during the “Asia-Pacific Peace and Friendship Conference” held in Beijing, the “Justice Triumphs” archway was renamed the “Defend Peace” archway, and the stone lantern was removed, now replaced by a flower bed, which looks unusually abrupt.

(Comparison of the Archway: Then and Now)

The long corridor, without a doubt, is the best place to enjoy the scenery and rest during summer. Although the scale of this corridor is not as grand as the one in the Summer Palace, walking through it still evokes a sense of wonder. When I pause to observe the paintings on the beams and rafters, I recall my grandfather telling stories about the corridor’s paintings in the Summer Palace to the younger generations. His voice was loud and clear, almost as if he were lecturing, attracting many passersby to stop and listen.

Walking along the corridor to the east of the south gate, not far to the left, there is a peculiar tree with intertwined pines and locusts. To the right is a courtyard surrounded by white fences and rose walls. In the center of the courtyard, a white Taihu stone highlights the elegance of the northern buildings. This is a traditional structure with four beams and eight pillars, black-tiled Xieshan-style roofs, red brick walls, and green glass wooden doors. The verandas are decorated with carved beams and painted rafters. A couplet on the red-painted corridor columns tugs at the heartstrings: “Do not let the beautiful days of spring and autumn pass by; the hardest thing is for old friends to visit during stormy weather.” Above the door, a plaque reads from right to left: “Laijinyuxuan.”

(Walking through the long corridor feels like traveling through a time tunnel.)

Pushing the door open and entering, the hall is fully occupied yet entirely free of noise. Soft background music sets off the unique atmosphere of this teahouse. A server in traditional Chinese attire guides me to a seat at the bar. I order a single-person set: four small pieces of yellow rice cake, four small side dishes, a famous winter vegetable bun, traditional covered bowl tea, and a small hot water bottle, all exquisite and serene. Sitting next to me is an elderly woman who has ordered only tea and is drinking it thoughtfully by herself.

(Today’s Laijinyuxuan still exudes the charm of the Republic of China era)

(Group photo at Laijinyuxuan in 1921 during the establishment of the Literary Research Society)

As I look around the tea house, the spacious and comfortable seats of traditional Chinese tables and chairs stand in stark contrast to the crowded and simplistic style of “fast fashion” establishments. Despite the ample distance between people, everyone speaks in soft tones. For a moment, I feel as though I’ve traveled back to the 1930s. I can see Qian Xuantong on September 14, 1937, having breakfast here alone, as usual ordering his favorite wheat porridge and bread. However, that day he tasted the food as extremely bad for the first time. He sat back in his chair, reminiscing about the times he strolled here with Li Jinxi to drink tea. They, along with Zhao Yuanren, had heated debates here over the phonetic representation of the Roman letters b, d, and g, with Zhao Yuanren’s scheme ultimately prevailing. They discussed phonetic characters with Bai Dizhou and collaborated with Wei Jiangong to propose the creation of phonetic typefaces here. He also attended a “Mengjin Society” banquet and met Xiao Zisheng here, met with Dong Weichuan, and bid farewell to Lu Yuyan and his wife here. Fudingyi invited him and Li Jinxi to dine and discuss connected characters, and Yuan Dunli and Liu Tuo also hosted him for meals here. In 1927, he attended the engagement ceremony of Shen Yinmo’s second daughter, Lingying, and Chen Yada here. In 1934, he not only attended but also wrote the marriage certificate for Tang Lian and Zhang Jingjun’s wedding. In 1935, he, as a senior, couldn’t miss the engagement of his good friend Zhou Zuoren’s son, Zhou Fengyi, to Sun Jianzhi here. Laijinyuxuan was a favorite of the Qian family—on June 1, 1921, he and his eldest brother Qian Xun’s families celebrated his brother and sister-in-law’s birthday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. here, and his brother and sister-in-law held many birthdays here subsequently. On July 15, 1937, over a hundred people attended the engagement of his eldest son Bingxiong to Youxiang here, and he ran many errands for this engagement banquet. He can still recall New Year’s Day in 1917 when Zhang Jiating initiated a farewell tea party for their fellow townsman, the former president of Peking University, Hu Renyuan, and they took a group photo in the backyard. This was his first visit to Laijinyuxuan, and he has been enjoying the elegant atmosphere here for twenty years. When Beiping fell, many old friends either went south or west, Zhongshan Park reverted to its original name “Central Park,” and Zhonghai was requisitioned by the puppet government. Afterward, Qian Xuantong, plagued by illness, rarely appeared at Laijinyuxuan again. Without “old friends,” how could there be “happy days”?

I began to carefully examine this building. The hundred-year-old beams include two sets of Chinese-style ridged rafters and two sets of Western-style I-beams, fully reflecting the blend of Chinese and Western styles in Republican architecture. The tea house still retains some of the early yellow and blue interlaced tiles, which were imported from Germany in 1915 and made with the then-emerging cement mosaic casting process. The intricate and durable patterns add an exotic touch compared to today’s simple flooring, bearing the footprints of countless visitors. It is recorded that Laijinyuxuan was built in 1915, also under the direction of Zhu Qiqian. Zhu Qiqian was the president of the Society for the Study of Chinese Architecture, with its office located in the western courtyard outside the Duanmen Gate of the Forbidden City, under the management of Zhongshan Park. Many members of the Society also served as directors of Zhongshan Park, often organizing exhibitions and elegant gatherings within the park, contributing to its artistic enhancement. Initially, Laijinyuxuan served as a meeting place for the park’s board of directors, later transforming into a tea house. Its name originates from the preface to Du Fu’s seven-character quatrain “Autumn Narration”: “Often guests come by carriage and horse, old friends in the rain, new friends hesitate to visit in the rain,” signifying “old friends gather regardless of the rain, new friends hesitate.” The plaque of Laijinyuxuan was originally inscribed by the Beiyang Government’s President Xu Shichang but was later used as a chopping board in the kitchen during 1966. The current sign is written by a calligrapher. When Zhongshan Park first opened, people flocked to see this imperial garden, often filling it to capacity on holidays. Laijinyuxuan became a favorite of literati and scholars, a significant social venue and cultural salon during the Republican era, attracting many prominent figures from various fields.

Strolling up the staircase on one side of the teahouse, I discover that the second floor only comprises partial sections at either end of the building and does not connect through, offering a relatively private setting. Each section is about the size of a meeting room for a dozen people, which explains why this place became a venue for many academic meetings. Historical gatherings, such as the Literary Research Society and the Philosophy Research Society, were established here. At one point, the National Language Promotion Committee frequently used this space for meetings, which conveniently allowed for dining afterward. The Dictionary Compilation Office also used this location to entertain visiting officials. For instance, in 1935, after inspecting the housing situation of the Compilation Office at Zhonghai, Inspector Xie Shuying from the Ministry of Education was hosted here for a meal by Li Jinxi and others. That same year, Gao Mengdan arranged a gathering of Simplified Chinese advocates at Laijinyuxuan, and Liu Shenxu’s brother, Liu Rongji, chose this venue to host a thank-you meal for his brother’s old friends.

From the second floor, looking down on the first floor, the high-ceilinged hall appears spacious and grand, with a lively yet orderly atmosphere. It’s no wonder that so many people preferred to hold their weddings here, including the veteran members of the Compilation Office like Wei Jiangong and his wife. Amidst the joyous laughter, Zhang Henshui, sitting quietly in a corner observing everything, used this setting as the backdrop for his novel “A Tale of Laughter and Tears.” I wonder if my grandfather ever visited Laijinyuxuan. It seems undeniable; after all, he was also a veteran of the Dictionary Compilation Office. Back then, going to Zhongshan Park for tea might have been as routine as going to Starbucks today.

In fact, Laijinyuxuan was not the only teahouse in Zhongshan Park. It was considered one of the higher-end, Sino-Western fusion teahouses. Along the west wall of the park, there were three generations of teahouses lined up from south to north: Chunminguan, Changmeixuan, and Bosixin.

“Chunminguan” was a chess and tea house with an elegant name. Its plaque was also written by Xu Shichang and hung prominently above the main entrance. The poetic couplet on either side of the entrance reads, “Spring rain, apricot blossoms, guests by the river; clear lake, willows at dusk, poetry in the evening,” with the first characters of each line forming the name of the teahouse. Inside, another couplet on the front wall reads, “Famous garden, a different world; old trees, unaware of the seasons,” aptly describing the natural environment of Chunminguan. The main clientele were city residents, mostly elderly former Qing dynasty officials and seniors who wore traditional long robes and visited the park to enjoy a fragrant cup of tea, giving the place a nostalgic atmosphere and earning it the nickname “Elder Hall.” Huang Jie, one of the “Four Great Poets of Modern Lingnan,” was a regular at Chunminguan. Tan Qixiang once encountered Lin Gongduo at Chunminguan, who spoke in classical Chinese, often punctuating his sentences with, “Tan Jun, do you agree?” After 1949, the teahouse was leased out to operate as a Chinese restaurant and tea shop, but it eventually went bankrupt and ceased operations after a fire. It was demolished in 1970 during the construction of the “May 19th Project.”

“Changmeixuan” rented the “Shanglinchun” building and operated as a plain teahouse. Its most distinctive feature was its rich cultural atmosphere. The teahouse stocked many books and subscribed to newspapers for patrons to read. The clientele mainly consisted of intellectuals and educators, including many writers and editors, as well as literati and company employees. Every day around four or five in the afternoon, they would gather here in groups, briefcases in hand and cigarettes in mouth. This was almost a daily routine for them. Some would drink tea, some would read, and others would chat. Unlike the elderly patrons of Chunminguan who indulged in nostalgic “idle chatter,” the discussions here revolved around current affairs, domestic and international news, and topics related to “Mr. Democracy” and “Mr. Science,” highlighting the social responsibilities of intellectuals since the May Fourth Movement. They engaged in lively debates, connecting the past with the present and navigating complex issues, giving the place a scholarly air and earning it the nickname “Park Council.” Renowned literary figures like Hu Shi, Fu Sinian, Qian Xuantong, and Wang Yi were regular patrons, each with their own dedicated seats. Because many of the visitors were middle-aged men, it was also known as the “Father’s Generation Teahouse.” In 1941, the teahouse was forced to close due to unpaid debts.

“Bosixin” sounds like a foreign name, but it actually originates from a line in the “Book of Songs”: “The fragrance of the pines and cypresses.” Given that there were few pines in Zhongshan Park and many ancient cypresses, the “pine” character was omitted. This teahouse was a popular spot for young people to meet, date, and enjoy tea, earning it the nickname “Youth Club.” Among all the teahouses in and around old Beijing, Bosixin was the liveliest, attracting the most female patrons, which was extremely rare for a Beijing teahouse at the time. Modern young women would proudly come here with their Western-dressed boyfriends, engaging in lively conversations without any reservations. Additionally, young men and women from wealthy families and students from Western-style schools were regular visitors. The teahouse offered Western-style refreshments, such as a cup of “Saturday,” a plate of “curry puffs,” and a place to sit and chat, reminiscent of the poem, “Looking back at the old Beijing in the teahouse, young beauties with rosy cheeks at Bosixin.” Their discussions differed from the elderly chatter at Chunminguan and the worldly debates at Changmeixuan, focusing instead on social trends like waltzes, tangos, “quicksteps,” and “foxtrots,” as well as the latest films like “Street Angel” and “Crossroads.” They would discuss movie stars and hum popular songs. The teahouse catered to their tastes by subscribing to cultural and entertainment magazines like “Liangyou” and “Sanliujiu,” for their reading and enjoyment. In 1937, Bosixin teahouse changed its lease and became the Jishilin Café. By 1956, during the period of public-private partnerships, it merged into the Ruizhenhou Restaurant, significantly altering its original business model and offerings.

(When Chunminguan opened, Zhu Qiqian and others took a group photo in front of the teahouse.)

(The outdoor tea seating area under the wisteria in Zhongshan Park.)

The Shui Pavilion, built along the water, is a picturesque structure with surrounding promenades, rippling green waves, and fluttering willows. It is the only waterfront pavilion in the park, offering a delightful view. This location has also served as a venue for meetings, exhibitions, and weddings. To the west of the Shui Pavilion, an artificial island formed by piled rocks creates a small hill. On this island stands a “工”-shaped building, originally a Guan Di Temple, later renamed “Siyixuan,” another spot for tea and rest. The scenery here is pleasant year-round, making its name fitting. Liang Shiqiu once praised this place highly, saying, “In spring, there are flowers; in autumn, the moon; in summer, cool breezes; in winter, snow.” This spot held a special place in his heart, as it was where he courted his wife, Cheng Jishu, enjoying tea at Siyixuan. Once, they even bumped into his father here, who, instead of reprimanding them, generously gave him money for tea, showing his open-mindedness and ultimately blessing Liang Shiqiu’s marriage.

Tea houses, a nearly vanished venue, were once cherished gathering places for many. They served an important role in information exchange, perhaps akin to a physical version of “Weibo.” Historian Xie Xingyao once wrote, “Anyone who has been to Beiping deeply misses the teahouses in Zhongshan Park. Many friends from both China and abroad who have traveled the world told me that the best place in the world is Beiping, and the best place in Beiping is the park. The most comfortable place in the park is the tea seating. One can temporarily forget all sad things there; at that time and place, at a wooden table, on a rattan chair, with a pot of fragrant tea, one seems to find great comfort.”

During the Republic of China era, the entrance fee for Zhongshan Park was 5 cents, which was relatively expensive for ordinary people. Therefore, regular visitors were mainly intellectuals with higher incomes, such as professors, doctors, and officials, contributing to the park’s rich cultural atmosphere. These individuals would invite colleagues and friends for leisurely strolls and discussions, much like Li Jinxi who often gathered peers for academic talks. Sometimes, they would serendipitously meet others in the park, expanding their group; other times, they would encounter someone they preferred to avoid and would have to discreetly find another path. When it snowed, they would come to drink tea and tread through the snow; when flowers bloomed, they would enjoy poetry and flower viewing; and when it rained, they would sit quietly and listen to the rain, savoring the moment. Even after 1949, when the park’s management and atmosphere changed significantly, many people’s habits of visiting the park remained unchanged.

My grandfather once recorded: “In the spring of 1964, old colleagues from the Compilation Office gathered in Zhongshan Park. Many attended, including Li Jinxi, He Danjiang, Xiao Jialin, Kong Fanjun, Sun Chongyi, Niu Wenqing, He Meicen, Zhang Weiyu, Yi Xingwu, Huang Jiabin, Zhao Shanzhai, Gao Jingcheng, Xu Shirong, and Wang Shuda. After some conversation, everyone got up to stroll in groups and view the flower exhibition.” Among them, some discussed academic matters, others talked about school work or current affairs, but most reminisced about their work and life at the Compilation Office.

Indeed, Zhongshan Park was a great place for socializing due to its excellent location, pleasant atmosphere, and culinary delights. During festivals and holidays, a group of close friends or colleagues, or a family with children and elders, would come to enjoy the scenery, exhibitions, and photography, always bringing endless joy. Flower viewing was also an important part of visiting Zhongshan Park. When I was a child, Tanghuawu was a greenhouse that hosted seasonal flower exhibitions throughout the year. My grandmother loved flowers and always had various plants in our yard. She especially loved chrysanthemums, and every autumn she would take her sisters and the children to see the flowers. I, of course, went along and even had my picture taken with chrysanthemums as big as my face, leaving a mark of that period in my life.

As I walk through the park now, with the gentle breeze on my face, the sunlight just right, the dappled shadows of the trees, and the faint fragrance of flowers, the ancient buildings still give the park a sacred and mysterious aura of an imperial garden. At one time, Zhongshan Park was simply referred to as “the park” by Beijingers, indicating its unique irreplaceability and their affection for it. Suddenly, within this park, as I feel the history and culture and enjoy the beauty of nature, I seem to step into my grandfather’s shoes and enter his heart. Like all Republic-era literati, he was knowledgeable, meticulous, and emotionally rich. Influenced by traditional Chinese culture, they had to keep all their emotions internalized and could not express them freely. Despite experiencing the vicissitudes of life, the dilemmas in academia and career, major family upheavals, and the scattering of children, no one could discern my grandfather’s thoughts. He always treated everyone around him with a smile and gentleness, never once losing his composure.

When he strolled in the park, it was like the deeply troubled Qian Xuantong, weighed down by family matters, the pondering Li Jinxi, trying to figure out how to secure funds, or Wang Yi, torn between accepting a puppet government position and abandoning the dictionary compilation. Although they could not completely escape their worries, touching nature and culture allowed them to temporarily forget their troubles and pains, to settle their minds. The beauty of the park and the time spent strolling provided them with the best healing. In this way, they completed their integration with nature and reconciliation with themselves.

Of course, for me today, revisiting the familiar environment, reminiscing about the past, and remembering loved ones who have passed away is more than fitting.

June 20, 2024

References:

“A Hundred Years of Zhongshan Park in Beijing” by Dai Xuefeng (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Tourism Research Center) (October 2014)

“The ‘Three Generations of Teahouses’ in Zhongshan Park” by Dong Mengzhi, Beijing Evening News

“Qian Xuantong’s Diary” edited by Yang Tianshi, Peking University Press (August 2014)

Confession Materials of Wang Shuda during the Cultural Revolution