The National Language Movement Struggles Forward

Author: Yun Wang

“When mentioning ‘movement,’ people in mainland China immediately think of words like ‘the whole nation participates’ or ‘vigorous and intense.’ However, the National Language Movement is different. It is like a candle, with a faint light, constantly flickering in the wind and almost extinguished, yet it strives to burn, to shine, to give warmth, unwavering until the end. The reason for describing the National Language Movement in this way is that it began only as the voices of a few scholars, without government support or organization. These individuals, motivated by a conscience to save the nation and strengthen the people, initiated this movement. They relied on their profound knowledge of classical Chinese studies, language expertise, open-mindedness, and reflections on Western progress. Thus, they started what later generations consider a startling and far-reaching movement.”

In the early stages of the National Language Movement, Lu Zhuangzhang from Fujian, after studying English in Singapore, used the ‘phonetic characters’ created by foreign missionaries to develop ‘China’s first fast phonetic alphabet.’ His goal was to make it so that once people learned the alphabet and phonetic method, they could read any character independently without a teacher. Six years after his textbook was published, during the year of the Hundred Days’ Reform (1898), his compatriot, a court official named Lin Lutun, petitioned the Censorate to request that the Emperor order the Ministry of Education to select scholars to research various regional simplified characters and phonetic methods. Emperor Guangxu ordered the Zongli Yamen (Office of Foreign Affairs) to ‘examine thoroughly and report.’ However, the political upheaval and wars left the court distracted. Another seven years passed before Lu Zhuangzhang presented his phonetic characters book to the Ministry of Education, which then passed it to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and back to the Ministry of Education. The following year, Lu submitted a new book, ‘Chinese Phonetic Alphabet,’ which used strokes instead of the Roman letters initially borrowed from foreigners. The Ministry forwarded his book to the Translation Bureau, which responded with a lengthy 3,000-character critique, dismissing it as ‘stuck in the present and neglecting the past, focused on the near and ignorant of the distant, resulting in various shortcomings.’ After fourteen years, Lu’s invention only spread in his hometown.

Compared to Lu, Wang Zhao was luckier, partly due to his civil service background. Although he invented his ‘Mandarin Phonetic Alphabet’ while in exile in Japan, making it inconvenient for public promotion, he leveraged his social connections, such as Hanlin Academy editor Yan Xiu, Tongcheng School elder Wu Rulun, and Zhili governor Yuan Shikai. This allowed him to introduce the phonetic alphabet at the Enlightenment School in Zhili. Later, other officials like Liangjiang governor Zhou Fu and Shengjing general Zhao Erxun also established ‘simplified character schools’ in provincial capitals. By 1906, Wang’s alphabet spread widely, from Beijing and Tianjin to Nanjing, reaching thirteen provinces. Wang Zhao’s success can be attributed to three factors: first, his alphabet was based on Beijing Mandarin, which made it easier to gain official recognition; second, he had connections in Beijing due to his government service. However, early in the Xuantong era, Wang Zhao and his Mandarin alphabet faced suppression. Like Lu’s invention, Wang’s was never officially recognized by the government or any academic organization. Only a few like-minded individuals promoted it within their own circles.

From this, it is evident that the National Language Movement initially was a grassroots initiative, concentrated in coastal areas where missionary activities flourished and culturally developed regions around Beijing. Their goal was to improve literacy among the Chinese people. Despite having enlightened rulers and capable ministers, the Qing government had too many internal and external concerns. Moreover, an ignorant populace was a tool of control for the feudal regime. Thus, this phase of the National Language Movement lacked government support, had no dedicated research institutions, and was not systematic or widely promoted. Nonetheless, these pioneers of the late Qing dynasty, with their efforts, brought a ray of hope to the illiterate masses, bringing hope to them and to China.

The second phase of the National Language Movement entered the Republic of China era. In 1912, the Ministry of Education passed the ‘Phonetic Alphabet Adoption Act’ and established the Committee for Pronunciation Unification. However, the first meeting was chaotic, with constant arguments and disorder. This meeting lasted for three months; Chairman Wu Jingheng resigned, Vice Chairman Wang Zhao fell ill, and finally, Hebei representative Wang Pu was hastily appointed as temporary chairman to conclude the meeting. Zhang Binglin’s phonetic alphabet was unexpectedly approved, primarily because many delegates at the meeting were his students. The 6,500-character pronunciation dictionary, passed on a one-vote-per-province basis, was also an incomplete effort due to the long voting process. Yet, no sooner had the meeting ended than the political situation shifted, resulting in personnel changes within the Ministry of Education, leaving all the resolutions to gather dust, unexamined. Only Wang Pu, with funds from members, founded the Phonetic Alphabet Learning Institute, working diligently to promote and disseminate it. This period, at the beginning of the Republic, was marked by systemic changes, making many issues unprecedented challenges. The chaos of the first Pronunciation Unification Meeting was a microcosm of the era’s democratic governance.

In the fifth year of the Republic (1916), the National Language Research Association was founded under the Ministry of Education, initiated by insightful individuals like Chen Maozhi, Lu Ji, and Li Jinxi. This academic organization advocated for ‘consistency between spoken and written language’ and ‘unification of the national language,’ goals met with strong opposition from figures like Lin Shu and Hu Yuji. Fortunately, Cai Yuanpei, then president of Peking University, served as the association’s first president, lending academic authority to its cause. At its inaugural meeting, it drafted the ‘National Language Research and Investigation Plan.’ With the New Culture Movement in full swing, the ‘literary revolution’ and ‘national language unification’ merged into a single current. Leaders of the New Culture Movement, such as Hu Shi, Qian Xuantong, Liu Fu, and Shen Yinmo, also joined the National Language Movement. By 1920, the National Language Research Association had 12,000 members. With the involvement of universities like Peking University and Beijing Normal University, the academic atmosphere surrounding the National Language Movement grew stronger. However, this phase was more akin to a brainstorming period, with more discussion than action.”

“The establishment of the Preparatory Committee for the Unification of the National Language (hereinafter referred to as the ‘National Language Committee’) marked the official entry of the National Language Movement into the stage of government operation, and the year was 1919. The first action taken by the National Language Committee was to announce the phonetic alphabet, which came seven years after the phonetic alphabet had initially been approved in 1912. Subsequently, the ‘National Pronunciation Dictionary’ was officially published, the ‘Revised National Pronunciation Dictionary’ was issued, the committee for ‘Expanded and Revised National Pronunciation Dictionary’ was established, the Chinese language curriculum in schools was renamed as the National Language curriculum, and reforms and optimizations were made in the education system. So, did the National Language Movement finally enter a smooth path of progress? Far from it.

At that time, the Beiyang Government’s control over the regions was extremely lax, resembling a confederate system, which in mainland China is called the ‘Warlord Era.’ This meant that regional power was greater than central authority; while the central government would issue policies, local governments acted independently. Furthermore, even within the central government, there were anti-national language forces, such as Zhang Shizhao, leading to new confrontations. However, this time the National Language Committee held some authority and was no longer as passive as it was in the early Republic.

Hu Shi was seen by the opposition as the commander-in-chief of the vernacular movement; he and the advocates of new literature and the young intellectuals defended the vernacular language. Lu Yiyan became the commander-in-chief in the publishing field, where the most critical battleground was the fight over national language textbooks and publications. Within the Ministry of Education, the official battlefield was led by the vice president of the National Language Committee, Zhang Yilin. Li Jinxi and Qian Xuantong countered the opposition’s publication, ‘Jiayin,’ by publishing ‘National Language Weekly.’ Among the provinces, Henan was the most progressive, while Fengtian was the most unyielding, outright banning the use of colloquial writing and prohibiting the teaching of the phonetic alphabet.

Adding to the absurdity, due to the instability of the Beiyang Government’s power, the issue of unpaid wages became increasingly serious, with the scope of unpaid wages expanding. Initially, only teachers were affected, but eventually, it extended to officials, from initially missing a month or two of pay to eventually being a year behind, forcing even professors to borrow from loan sharks to make ends meet. Meanwhile, the student autonomy movement was in full swing, with frequent strikes, and officials in the Ministry of Education, like those in other departments, changed frequently, even leading to periods of vacancy, leaving no one with the energy to carry out the work of the National Language Committee. It should be noted that all members of the National Language Committee were part-time, and with no salaries being paid for their main jobs, there was even less incentive to pay attention to part-time tasks.

Thus, this phase of work was not neglected by the government due to a lack of importance but due to sheer helplessness. During this phase, the conflict escalated to a factional level. It was no longer merely a matter of language but of culture, and even more so, of politics.”

“The members of the National Language Committee did not stop; they continued along the path they had designed and began the next stage of their work, designing and promoting the Romanization of the National Language, which they saw as a step toward aligning with international languages. Administratively, progress remained challenging: it was only at the fifth conference of the National Language Committee in 1923 that a committee was organized to revise the ‘National Pronunciation Dictionary,’ continuing a plan set four years earlier. However, this committee did not formally meet until December 1925, when members were appointed. The meetings were full of difficulties, with many members either absent or represented by proxies, and the proceedings were awkward and challenging.

In 1928, when the National Revolutionary Army unified the north and south, the stability of the government greatly strengthened the promotion of the National Language Movement. That year, the ‘Romanized National Language’ was published, the China Dictionary Compilation Office was established, and provinces and cities were ordered to set up ‘Phonetic Symbol Promotion Committees.’ Just as the National Language Movement seemed to be advancing rapidly, the September 18 Incident (Mukden Incident) occurred. Fortunately, by then, the one-party dictatorship had been established, and with the national crisis at hand, the Kuomintang deeply understood the importance of various forms of unification. They mandated the use of vernacular language, phonetic symbols, Romanized National Language, and punctuation by party and state agencies, extending this to radio, wired broadcasts, railways, and the judiciary. Romanization and shorthand training centers were set up across the country, and the Ministry of Education issued new ‘Primary and Secondary School Curriculum Standards,’ which also spurred the rise of public education.

However, despite the apparent momentum of the National Language Movement, it was actually struggling financially. Since the time of the Beiyang Government, the fiscal crisis of the Nationalist Government had never been resolved. Universities were not only severely behind on salaries; students frequently went on strike, and when classes were canceled, salaries were also reduced. Budget allocations for institutions like the National Language Committee were extremely difficult to secure each year, and even then, there was no guarantee that the funds would actually be disbursed. Consequently, people like Li Jinxi and Wang Yi, who had some connections within the Ministry of Education, also took on the responsibility of fundraising. They not only sought budget support but also explored other avenues, such as approaching educational foundations and soliciting donations from like-minded individuals, but were met with obstacles everywhere.

The China Dictionary Compilation Office, which had ambitious plans in 1928, often faced a shortage of resources. In April 1933, when Ministry of Education official Zhang Xingfang visited the office, Li Jinxi immediately asked him to urge for funds. In July, the Ministry allocated another 12,000 yuan to the office, which greatly excited everyone because their work could continue uninterrupted. In August, receiving funds according to the budget became a rare occasion worth celebrating. However, in May 1935, the budget was once again cut. After extensive lobbying, the allocation in July was reduced to 11,000 yuan, leading Li Jinxi and others to revise their work plans, reduce personal compensation, and make adjustments to keep the compilation office running.”

“Another unexpected challenge the National Language Movement faced was the loss of personnel, especially the untimely deaths of core members. Among them were Liu Bannong, who had just completed his PhD in phonetics in France and passed away from a fever contracted during a northwest expedition in July 1934; Bai Dizhou, who died in October 1934 at the young age of 34, yet had played an important role in both linguistics and the National Language Movement; and Ma Lian, who suddenly died of a cerebral hemorrhage while lecturing at Peking University in February 1935. His death had a significant impact on the middle-aged, physically and mentally exhausted professors. The ailing Qian Xuantong once expressed a desire to focus solely on the national language work rather than continue teaching, as his health could no longer keep up, and he was particularly frustrated with the difficulties of organizing classes and mediating irreconcilable conflicts between faculty and students as a department head. Li Jinxi, meanwhile, was struggling with being expelled by students, dealing with strikes, and constantly seeking connections to secure funding and personnel for the National Language Committee and the Dictionary Compilation Office. Over time, interpersonal conflicts within the committee also surfaced—some academic, others personal. Sun Zishu, for example, left because he couldn’t work with others.

In 1935, the Ministry of Education reorganized the National Language Committee into the National Language Promotion Committee. The subsequent war with Japan and the fall of Beijing brought this organization and its work to a complete halt. At the same time, the ‘Latinization Movement’ led by domestic leftists sparked debates and criticism of the National Language Movement. This was followed by the third phase of the movement. This period coincided with the War of Resistance Against Japan. Members of the committee scattered: some, like Wei Jiangong, moved south; others, like Li Jinxi, went west; some, like Qian Xuantong, stayed in enemy-occupied areas and passed away there; others, like Wang Yi, remained in the occupied zone to carry on the original plan; and others, like Zhao Yuanren, went abroad to lecture. They were never able to gather again, but each continued to contribute to the National Language Movement in their own way: Wei Jiangong went to Taiwan, which had limited exposure to Mandarin, and led the Taiwan National Language Promotion Committee, laying the foundation for the future promotion of Mandarin in Taiwan; Li Jinxi established a department for Mandarin studies at universities in the northwest, training language teachers for places like Taiwan; Qian Xuantong, until his death, continued to refine his ‘Common Vocabulary of Mandarin’ and began compiling a new dictionary; Wang Yi, working under the puppet government, completed the compilation of the eight-volume ‘National Language Dictionary’ with a few remaining members of the compilation office. Despite being in different places and under harsh conditions, they continued this shared mission with a sense of mutual understanding. In 1949, as an era in China came to an end, Li Jinxi completed the official preface to the ‘National Language Dictionary’ and published a four-volume edition. This monumental work defined the standards for Mandarin and the methodology for compiling a national language dictionary, laying the foundation for the promotion and development of Mandarin in mainland China, Taiwan, and worldwide, and marking a perfect conclusion to the National Language Movement.

The National Language Movement began unconsciously among pioneers who aspired to create a language that could be written as easily as it was spoken, so that Chinese people would no longer have to spend so much time learning to read, and so that Chinese would become unambiguous and logical, aligning with world languages. From this perspective, the National Language Movement still has a long way to go. Today, China has made great strides in eradicating illiteracy, yet Chinese has not achieved full unification. Instead, different systems have emerged, such as Pinyin and simplified characters, Zhuyin and traditional characters. Will there be a next phase of the National Language Movement? Perhaps we are merely in a pause within this ongoing movement.”

References:

Diary of Qian Xuantong (Edited Version), Chief Editor: Yang Tianshi, Peking University Press

Outline of the History of the National Language Movement, by Li Jinxi, Commercial Press

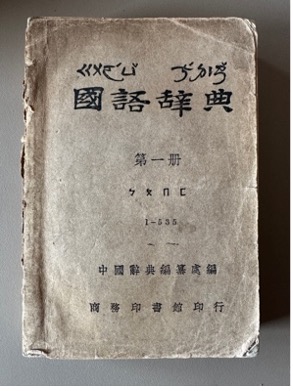

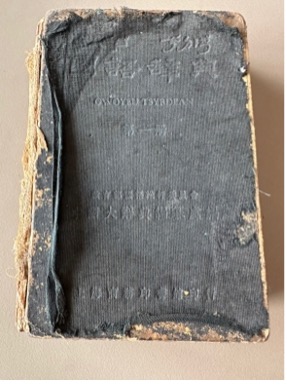

National Language Dictionary (Eight-Volume Edition)

Chief Editor: Wang Yi

Compilers: Xu Yishi, Sun Chongyi, Wang Shuda, Peng Xinru, Xu Shirong, He Meicen, Fu Yan, Niu Wenqing

Authored by: China Dictionary Compilation Office

Publisher and Printer: Commercial Press

Date: December 1943

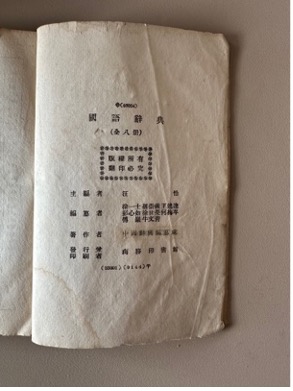

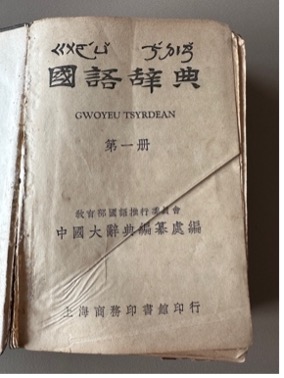

National Language Dictionary (Four-Volume Edition)

Chief Editors: Li Jinxi, Wang Yi

Compilers: Xu Yishi, Sun Chongyi, Xu Shirong, Fu Yan, An Wenzhuo, Wang Shuda, Zhang Weiyu, He Meicen, Niu Jichang, Gao Jingcheng

Authored by: China Dictionary Compilation Office

Publisher: Commercial Press

Date: (1937-1947)

(The National Language Dictionary (Eight-Volume Edition))

(The National Language Dictionary (Four-Volume Edition’s First Volume))