Perseverance and Commitment - A Remote Dialogue with Mr. Peter Wang

Author: Yun Wang

Mr. Peter Wang is a household name in Taiwan. Strictly speaking, he could be considered a “tech guy,” as he earned a Ph.D. in electrical engineering in the United States, worked for well-known companies, and served as a university professor. However, his success lies in his transition to becoming a renowned director, actor, and writer. His film Beijing Story vividly captures the essence of Beijing’s culture, and his trilogy of books, A Decade of Struggles: A Naughty Boy, Playful as Ever: A Young Man, and Ambitious: A True Man, humorously and intriguingly depicts his adventurous and legendary life. This time, my cousin and I had the rare opportunity to engage in a direct conversation with Mr. Wang Zhengfang.

We address Mr. Peter Wang as “Uncle Wang” because his father, Mr. Wang Shoukang, and our grandfather, Mr. Wang Shuda, were both esteemed students and assistants of Mr. Li Jinxi, as well as colleagues at the Chinese Dictionary Compilation Office and the Mandarin Specialized Department of Beijing Normal University. Although we have known Uncle Wang for more than five years, this was the first time we had a direct dialogue due to living in different regions across the Taiwan Strait. Given the connection to the unfinished work of our predecessors, the experience was truly exciting.

Today, when Chinese speakers can communicate fluently in Mandarin and have tools like Mandarin dictionaries to aid in their reading and learning, most people are unaware that this was entirely impossible in China a hundred years ago. At that time, Chinese people from different regions struggled to understand one another, like “a chicken talking to a duck.” Literacy was dependent on private tutors and extensive self-study, but tutors from different regions had various dialects and systems. In 1909, as many regions in China began to adopt Western-style voting systems, it became evident that democracy was unfeasible in China at the time because the majority of people were illiterate—how could they vote? Thus, in the early years of the Republic of China, reformers who had long been advocating for the National Language Movement expanded it across society. They developed phonetic symbols, standardized pronunciation, compiled dictionaries, promoted education, and established China’s own linguistic system, benefiting Chinese people to this day. These pioneers of the National Language Movement demonstrated courage, wisdom, a strong sense of social responsibility, and unyielding determination, and they deserve to be forever remembered.

Our conversation with Uncle Wang was rooted in this shared understanding. Uncle Wang spoke of how, after graduating from university, his father began teaching in a middle school in Beijing before joining the army during the Northern Expedition, where he taught Mandarin to soldiers. He strictly followed Mr. Li Jinxi’s methodology, teaching phonetic symbols first and then Mandarin. His clear and standard pronunciation earned admiration. On one occasion, a commanding officer with a strong Shandong accent praised him. At this point in the story, Uncle Wang humorously mimicked the officer’s Shandong dialect, making us all laugh. This imitation was likely something Mr. Wang Shoukang had performed at home for his son, showcasing his cheerful, humorous, and eloquent personality, as well as his immense pride in teaching Mandarin. Decades later, Uncle Wang still vividly remembers this incident, reflecting his keen observational skills, excellent memory, and deep respect and fondness for his father.

Speaking of his father’s dedication to the Mandarin language, Uncle Wang shared more stories. He said that during the early years in Taiwan, economic conditions were poor, and many people gave up their professions to go into business. One of Mr. Wang Shoukang’s former students, Zhang Boyu, jokingly suggested that Mr. Wang lead a business venture so everyone could earn money instead of sticking to language education. Mr. Wang sternly rebuked him, reminding him that no matter how difficult life became, they must continue teaching Mandarin because that was their belief. Mr. Wang Shoukang remained steadfast in his mission as a member of the Mandarin Promotion Committee in Taiwan. He established the Mandarin Specialized Department at Taiwan Provincial Normal College to train teachers, served as the deputy editor-in-chief of Mandarin Daily News—the world’s only newspaper combining phonetic symbols and Chinese characters—delivering its authentic content to Taiwanese readers, and went to great lengths to rescue his students who encountered political difficulties. These students, who taught in various primary and secondary schools, were his crucial allies in spreading Mandarin.

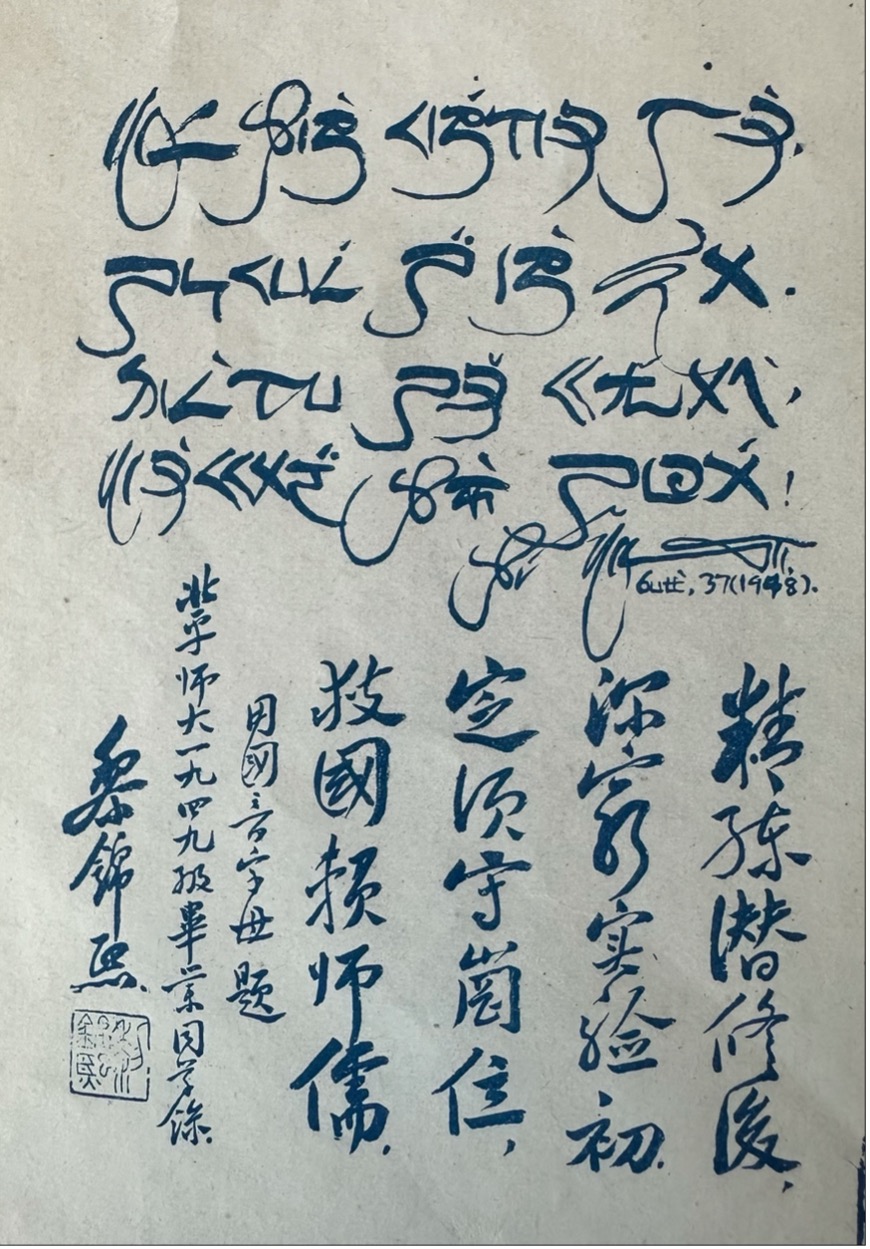

Speaking about his father’s students, Uncle Wang fondly and vividly recalled several names, such as Da Song, Zhai Jianbang, and Gong Qingxiang. These individuals were often around his father back in the day and were regarded by Uncle Wang as senior brothers. Now, they have all passed away, yet Uncle Wang still speaks of them with deep affection, filled with nostalgia. Hearing this, I told him that I could provide a photocopy of the 1949 graduation yearbook from Beijing Normal University that our family has preserved, which contains photos and information about these individuals. Uncle Wang nodded with satisfaction upon hearing this.

It must be said that it was precisely because of individuals like Mr. Wang Shoukang that Taiwan transformed from a place where Mandarin was virtually unknown to a region where it was most successfully promoted. Uncle Wang proudly shared that, over time, as many people in Taiwan received education, they became fluent in Mandarin but often lost their ability to speak local dialects. This even created communication challenges within families, as younger generations who spoke only Mandarin would struggle to communicate with elders who spoke only in dialects. This highlights the remarkable impact of the Mandarin promotion efforts at the time. In recent years, under the leadership of the Democratic Progressive Party, there have been suggestions to abandon the use of Mandarin. However, it became evident that local languages lacked corresponding written systems and were therefore unsuitable for official use. This underscores the tremendous contributions of the linguists from a century ago.

So, has the mission of the National Language Movement been fully accomplished today? Uncle Wang believes that in Taiwan, it can be considered complete, but he thinks the progress in mainland China has not been as successful as in Taiwan. When he returned to the mainland in 1971, he found that primary schools in Guangdong were still teaching in Cantonese. “Perhaps there have been too many movements,” he remarked casually, which may have touched on the root of the issue. Of course, given the vast territory and large population of mainland China, balancing the preservation of traditional regional dialects with the promotion of Mandarin is no simple task. However, with the rapid development of electronic technology, the spread of language and written systems has become significantly easier.

Beyond dissemination, the evolution of Mandarin itself is another important topic. The pioneers of the National Language Movement had various ideas and debates about the development of Mandarin. At one point, it was widely believed that Chinese characters hindered China’s development in science and technology. Since Chinese characters are pictographic and must be memorized individually, they were considered time-consuming and laborious to learn, particularly for young children. If Mandarin could be transformed into a language where speaking directly corresponded to writing, children could save significant time learning Chinese characters and instead devote that time to studying science and technology. Thus, some advocated abandoning Chinese characters as a functional tool and adopting a Romanized script to align with global standards. In the 1930s, members of the Numeral Society, led by Zhao Yuanren, invented the Romanized Mandarin system, which was promoted by the Nationalist government. At the time, this played an important role in unifying Mandarin in fields such as transportation and telecommunication.

Was this developmental direction correct? Uncle Wang expressed a negative view. He noted that the Romanized Mandarin system was never successfully implemented in Taiwan. With the advent of computer-based Chinese input methods, writing underwent a fundamental revolution, significantly increasing efficiency. As AI technology continues to advance, speed will no longer pose a barrier to learning and using Chinese characters.

In the development of Mandarin, Taiwan has largely followed the vision laid out by the National Language Movement, while mainland China has taken a different path by replacing traditional characters with simplified ones and substituting Zhuyin symbols with Pinyin based on Latin letters. Which approach is better? Uncle Wang favors Taiwan’s direction. He even bluntly remarked that in this regard, Wei Jiangong, a figure he deeply respects, could be considered somewhat of a “sinner.” This is because Wei Jiangong played a leading role in overturning the achievements of the National Language Movement and promoting simplified characters and Pinyin. While the simplification of many characters by adopting cursive-style forms did reduce the number of strokes, it also, according to Uncle Wang, stripped Chinese characters of their essence. Taiwan, to this day, continues to use the Zhuyin symbols introduced by the Nationalist government in the early 20th century. However, in recent years, some areas in Taiwan have started to accept and use Pinyin. This is partly for political reasons, such as New Taipei City under the pro-mainland Kuomintang government adopting Pinyin, and partly due to the widespread influence of mainland media platforms in Taiwan, which has created a homogenizing effect.

Beyond the writing system, one of the major principles of the National Language Movement was the use of vernacular Chinese. In this regard, the mainland seems to have done better, particularly by making written language more colloquial, accessible, and simple. However, in the process, it has also lost some of the original polite expressions, honorifics, and formal written language elements of Mandarin. Our generation often admires the rich vocabulary, allusions, and literary skills displayed in the writings of earlier times, but unfortunately, we lack the training to appreciate or use them. Uncle Wang expressed regret over this outcome, particularly because he feels that this trend of simplification in mainland China is influencing younger generations in Taiwan. Even in popular music, the profound lyrics of older songs are often more memorable. Nowadays, young people in Taiwan are experimenting with further simplifying written language, with some even using Zhuyin symbols to replace Chinese characters in writing. Interestingly, this aligns somewhat with the original intent of creating Romanized Mandarin, offering an intriguing perspective for exploration.

Speaking of our connection with Uncle Wang, it all began five years ago with the launch of our website, Speaking of Language and History. The website is dedicated to studying and commemorating the figures involved in the National Language Movement and represents a commitment to preserving its legacy. It is important to note that the National Language Movement, originally spearheaded by the then-ruling Kuomintang, has nearly faded into the annals of history on the mainland, with little public recognition. The individuals who participated in the movement had different fates depending on their paths and positions—some gained fame, while others have long been forgotten. Even in Taiwan, publications like the Mandarin Daily News, primarily read by elementary and middle school students, now rely on support from civic organizations to survive, struggling to stay afloat. Not long ago, Mandarin Daily News even underwent a major battle to defend its existence.

Our fledgling website is also taking tentative steps forward. Uncle Wang’s support and assistance have been a great source of encouragement for us. He has not only provided us with a deep understanding of the history and development of Mandarin in Taiwan but has also shared his insights into Mandarin and the National Language Movement without reservation. Without a doubt, Mandarin is one of the most important bonds and cultural legacies of the Chinese nation. Paying tribute to the National Language Movement and continuing to promote Mandarin should also be the responsibility and mission of our generation.

Li Jinxi inscribed for the 1949 graduation yearbook of Beijing Normal University