The Most Beloved Uncle Wang - Mr. Wang Shoukang

Author: Peter Wang

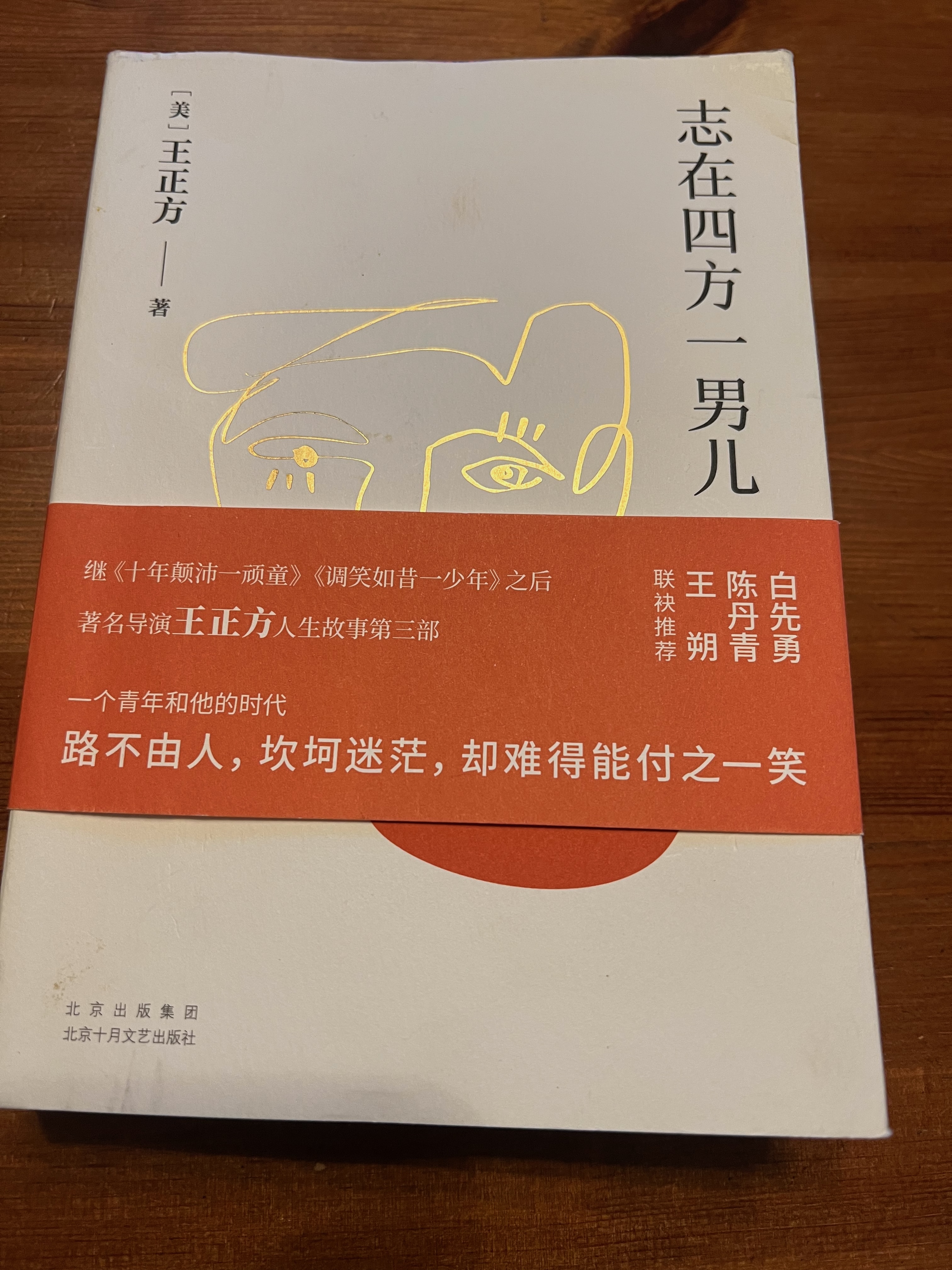

Excerpt from Ambitious Across the World: A True Man

Ambitious Across the World: A True Man

Chapter 9. The Most Beloved Uncle Wang

In the early days, when we lived on Chongqing South Road, Section 3, Alley 14 in Taipei, my father was the most beloved figure among the neighborhood children. As soon as they saw him coming from afar, they would stop playing and shout loudly, “Uncle Wang!”

With his short stature, bald head, a protruding belly, and round glasses with horn-rimmed frames, he was an unmistakable figure. Returning home from work, he had just stepped into the alley when children from all directions swarmed around him, calling out excitedly:

“Uncle Wang, tell us a story! Start with me!”

Surrounded by the children, Uncle Wang chuckled and pointed at one mischievous boy:

“Little He, did you get punished at school today?”

“No.”

“He’s lying! The art teacher made Little He stand in the corner.”

“Little He, Little He, well-fed and never hungry, but scared of art class!”

“Me next! Tell my story, Uncle Wang!”

“Ah Zhao, Ah Zhao, always jumping around and causing chaos. What’s not sold in Shanghai? Don’t hold your pee!”

This Ah Zhao loved playing so much that he would hold in his pee until it was too late, often wetting his pants. The children burst out laughing, and Ah Zhao’s face turned bright red, but he laughed along with them. Then it was Xiao San’s turn.

“Xiao San, Xiao San, munching on pickled radishes, pooping red and puffing red smoke!”

Xiao San was famous for his gluttony and loved buying random things to eat. One time, he ate something bad, which caused severe rectal bleeding. Xiao San’s mother blamed my father:

“Mr. Wang, it’s all because of your rhymes. Xiao San went and ate bad pickled radishes somewhere because of them.”

As my father approached our house, the kids still clung to him, shouting loudly:

“You haven’t told my story yet!”

“Go home now! Your moms are waiting for you to eat dinner!”

He would shut the door, and only then would the kids grumble and slowly disperse.

My father’s talent for composing rhymes on the spot was renowned far and wide. This skill was deeply connected to his childhood upbringing in northern China. Rural nursery rhymes in northern villages were rhythmic, humorous, and vividly descriptive—so memorable that one could never forget them after hearing them once. One such rhyme, Who Will Play with Me, was a favorite among kids growing up in North China. When I was little, my father taught us to sing it:

“Who will play with me, strike a spark?

A spark of fire, sell melons;

Melons are bitter, sell tofu;

Tofu is rotten, flip an egg;

Eggshell, eggshell, inside sits a brother.

Brother comes out to buy food,

Inside sits a granny,

Granny comes out to burn incense,

Inside sits a girl,

The girl comes out to light the lamp,

Burning her nose and eyes.”

My mother said that when I sang this as a child, I would flail my hands all over my nose and eyes after the last line.

(火燫儿: In northern Chinese villages, “打火燫儿” refers to the act of striking a piece of iron against a flint to create sparks to light a paper wick.)

My father continued, “Willow Tree That Willow was a nursery rhyme from our hometown. It went like this:

‘Willow tree, that willow! Pagoda tree, that pagoda!

Under the pagoda tree, a stage is set.

Other families’ girls have arrived,

But our girl hasn’t come yet.

As we talk, she arrives!

Riding a donkey, holding an umbrella,

Bare-bottomed, hair twisted into a bun,

Wearing clogs, toes sticking out,

Tucking a garlic bowl under her armpit.’”

This rhyme humorously teased the local girls and carried a somewhat chauvinistic tone.

As a child, my father was clumsy and terrible at farm work. His elder uncle, the family patriarch, believed that this boy was better suited for academics. By chance, a retired scholar named Wang Zhongxing had recently opened a private school nearby. Breaking tradition, the patriarch sent my father to study there, making him the first in the Wang family to receive a formal education. Unexpectedly, the scholar saw him as a rare talent, noting his excellent memory and comprehension skills, and encouraged him to pursue his studies further.

After two years of private tutoring, a modern school was established in the county. My father enrolled in its elementary program. He recalled his childhood studies: primarily the Four Books, with some math. Early Republican-era language textbooks began introducing Western ideas, including a story about American President George Washington chopping down a cherry tree.

The teacher would have students read the text aloud together, but nearby, an opera stage was loudly performing Hebei Bangzi opera. As a result, the students’ chanting unconsciously followed the opera’s rhythm. My father said, “The opera was singing Lady Wang Chun’e in her embroidery room, lamenting her fate, while we chanted, Washington in the backyard, swinging his axe to chop—yah hoo, yah hoo, hey—!”

My father excelled in elementary school, earning numerous accolades and subsidies for the school. The administration was so keen to retain these benefits that they refused to let him graduate. Eventually, he successfully passed the entrance exam for Beijing Normal University Affiliated Middle School, which was the top middle school in Beiping (now Beijing) at the time.

However, my father’s journey to getting into university was not smooth. He failed twice before finally being admitted to the Chinese Literature Department at Beijing Normal University on his third attempt. He told us it was all because of a photograph.

In the early Republican era, having a photo taken was a significant event. To prepare for the application process, my father meticulously dressed in a long robe and mandarin jacket, topped with a melon cap. He sat stiffly in a grand armchair, with a backdrop featuring a tall tea table adorned with a vase of flowers, a water pipe, and a tea set. At the time, my father was dark-skinned and skinny, and the person in the photo looked like a middle-aged man. While his test scores were excellent, the admissions committee thought he appeared too old and declined to admit him.

The following year, he applied again using the same photograph but faced the same outcome. Refusing to give up, he tried a third time and was finally accepted. Later, his professor, Xia Yuzhong, explained the backstory to him. Professor Xia had argued on his behalf during the admissions meeting, saying:

“This student has taken the exam three times and consistently achieved outstanding results. His perseverance is admirable. Although he looks older, his determination is commendable, and his academic foundation is solid. There’s no need to impose strict age limits on Normal University students. Older students can still become excellent teachers after graduation!”

In the early Republican era, Beiping (now Beijing) was known for its open and free academic atmosphere. Dedicated university students could learn from masters of various schools of thought. My father was taught by prominent figures such as Li Jinxi, Qian Xuantong, and Huang Kan—renowned scholars and titans of Chinese studies.

After graduating from university, the Northern Expedition of the National Revolutionary Army was underway, and my father was filled with fervor. He abandoned his literary career, heading south to join the Northern Expedition army, where he was responsible for propaganda and soldier education.

When the Northern Expedition concluded, he returned to Beijing and worked alongside Professor Li Jinxi in compiling the Mandarin Dictionary. Soon after, the Anti-Japanese War broke out, and with the nation’s survival at stake, he once again left his literary work to rejoin the military. He served as a lieutenant colonel instructor in the Third War Zone in southeastern China, where he organized newspapers, broadcast anti-Japanese programs, ran literacy classes for soldiers, and led a theater troupe to promote the war effort. His boundless energy and unwavering dedication made him seem as though he had three heads and six arms—never tiring, no matter how much work he took on.

After enduring the trials of two wars, my father, still a young man at the time, witnessed a nation weakened, its people impoverished, backward, and ignorant, facing the brutal realities of war like lambs to the slaughter. This left him deeply heartbroken. He believed that the prerequisite for a strong and prosperous nation was a citizenry equipped with modern knowledge. At that time, over 90% of the population in mainland China was illiterate, and promoting literacy to eliminate illiteracy was a top priority.

He firmly believed that a modern nation must have a unified language to enable effective communication, foster unity in nation-building, and resist foreign aggression. Teaching pronunciation correction with phonetic symbols was the first step in language education, and promoting Mandarin became his lifelong mission. He dreamed of a nation where everyone spoke in one unified voice, achieving “language harmony across the land.”

My father’s speech was pure, resonant, and powerful. His commentary on the world was insightful and vivid, and his everyday conversations were full of wit and charm. Zhao Lede, a family friend and daughter of Uncle Zhao Youpei, recalled:

“Back then, we siblings attended prestigious schools like the Beijing Normal University Affiliated Middle School and Taipei First Girls’ High School. We were proud and aloof, often feigning polite smiles when our parents’ friends visited, paying them little attention. But the moment Uncle Wang arrived, we would all rush out to surround him, eagerly listening to him talk. His appeal truly transcended generations.”

Uncle Wang was composed and eloquent, with a great sense of humor and a masterful command of language. Uncle Zhao Youpei would often invite my father to stay for meals at the Zhao family home, saying:

“There’s nothing special to eat, just a humble meal here at our place!”

Uncle Wang would correct him with a grin:

“The phrase ‘humble meal’ should never be prefixed with ‘big’ or ‘small’—it’s improper!”

Aunt Zhao, continually urging him to eat more, would pile food onto his plate. Uncle Wang, gesturing at his neck, would joke:

“That’s enough, that’s enough! I’ve already eaten so much I look like Duke Jing of Qi (齐颈, meaning ‘neck-level’).”

On hot summer days, Uncle Wang, with his sturdy build, carried a towel to frequently wipe away his sweat. Even so, he would still be drenched. One time, as he entered the house, dripping with sweat, he exclaimed:

“I must be the ancient Hanlin scholar (汗淋, meaning ‘sweating profusely’)!”

In the evenings, the Zhao family would sit outside in the courtyard enjoying the cool breeze, listening to Uncle Wang discuss current affairs and historical topics. Surrounded by mosquitoes, Uncle Wang finally had enough and shouted:

“Let’s go inside! Otherwise, we’ll all become Wei Wen Di (餵蚊弟, meaning ‘mosquito-feeders’).”

At the wedding of Lin Liang and Zheng Xiuzhi, two young editors at the Mandarin Daily News, my father delivered a speech:

“Their names combine to form the phrase ‘Xiulin Liangzhi’ (秀林良枝, meaning ‘beautiful forest and fine branches’). From now on, they will live in perfect harmony, and their children will surely be outstanding. Truly, this is a union made in heaven!”

In 1948, we arrived in Taiwan, where my father was invited by the Taiwan Provincial Department of Education to serve as a member of the Mandarin Promotion Committee. In Taiwan, he founded the Mandarin Daily News. Beyond running the newspaper, he often appeared on radio broadcasts teaching Mandarin. His co-broadcaster, Uncle Lin Liang, who was originally from Minnan, would translate into the Taiwanese dialect. The Taipei City Bureau of Education also enlisted him to run Mandarin classes for elementary school teachers. He helped Taiwanese film studios correct actors’ stage pronunciation, established the Mandarin Training Program at the Provincial Teachers’ University, and later founded the Mandarin Center to teach Chinese to foreign students. His daily schedule was packed and hectic.

Uncle Zhao Youpei fondly recalled my father’s brilliant speeches:

“When he took the podium, his delivery was powerful, captivating, and seamless. He made complex topics easy to understand, peppered with witty remarks that left his audience enthralled, grinning from ear to ear, and bursting into applause.”

I didn’t hear many of my father’s lectures on language education, but I remember one where he used The Dog with the Fancy Tail as a topic:

“A dog with a fancy tail is still a dog. A fancy dog tail is part of a dog, but a dog tail flower is a flower.”

He then crafted the following playful sentence:

“The dog with the fancy tail spun in circles, chasing its fancy dog tail, and bit off a dog tail flower.”

Examples like these were abundant in his talks, showcasing the intricate beauty of the Chinese language.

During a lecture trip to Taitung, so meone gifted my father an ebony walking stick. He loved it so much that he hugged it to sleep that night. Delighted, he said:

“From now on, I’ll use this walking stick to whack those foolish people who lack both benevolence and wisdom!”

Uncle Zhao always admired my father, describing him as a man of unshakable integrity and ironclad principles. He was straightforward, impartial, and fearless, a man who only grew tougher under adversity. His fiery personality and dedication to his work often left him completely absorbed, and he harbored a deep disdain for societal injustices. In his most spirited moments, he would often swing his walking stick dramatically or bring it down in a decisive chopping motion.

Language education was my father’s most steadfast belief. Once, a student of his wanted to change careers, and my father told him:

“Why not go to the market and sell vegetables? Just sell whatever happens to be in season!”

That student spent the rest of his life dedicated to the field of language education.

Another student, who initially failed his Mandarin pronunciation exam, eventually passed after retaking the course. He later recalled:

“If Teacher Wang had simply passed me back then, I wouldn’t be able to speak such beautiful Mandarin today.”

Li Zidá (the renowned director Li Xing) once took my father’s Mandarin phonetics class at the Provincial Teachers’ University. He believed his Mandarin was already perfectly standard and requested to skip the lessons. At the end of the semester, my father gave him a grade of 60. Director Li never did learn phonetic symbols.

Today, many people are hailed as “celebrity speakers” or “masters of eloquence.” In my humble opinion, most of them are unworthy of such titles. Throughout my life, I have only ever encountered one true master of eloquence: my late father, the man everyone affectionately called Uncle Wang.

The first requirement for being a “master speaker” is to have flawless pronunciation in a given language. Regardless of the language being spoken, if the speaker constantly mispronounces words or changes tones unintentionally, the listener’s comprehension is immediately diminished. If the speaker cannot even convey basic meaning clearly, how can we talk about anything deeper?

Only after achieving this foundation can we discuss the elegance, humor, and wit in one’s words, as well as the breadth of knowledge required to draw on a wide range of references. A true master must skillfully balance the weight and flow of their words, maintain logical structure, and deliver insights that leave listeners enlightened, as if a sudden clarity has dawned upon them.

As for the so-called “celebrity speakers” of today, I must say—with reluctance—they are far from deserving such praise. Best not to comment further!