After talking for three days straight, can’t do it anymore - Mr. Wang Shoukang

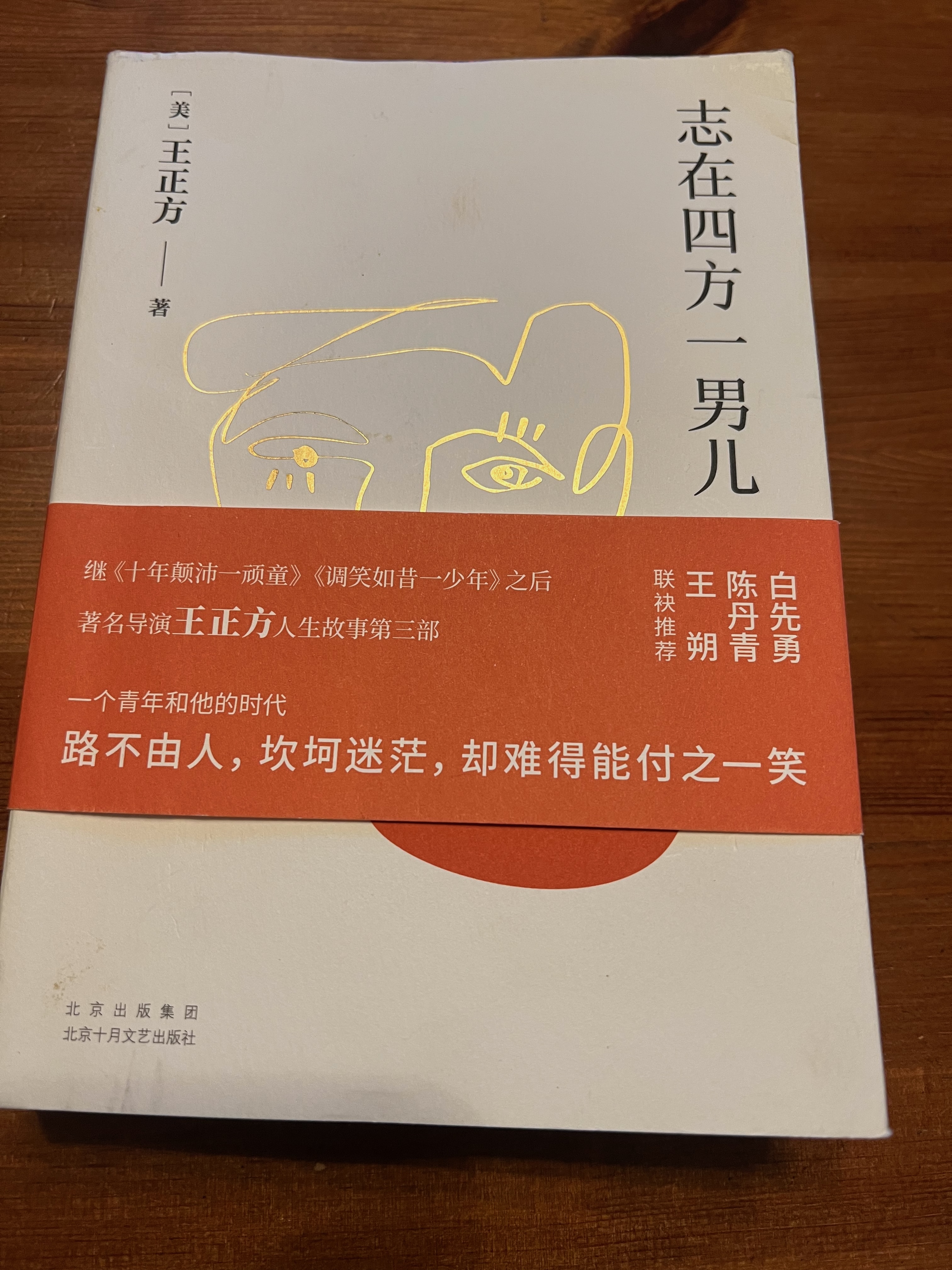

Author: Peter Wang

Excerpt from Ambitious Across the World: A True Man

Chapter 10.

I slept on a mat next to my father’s hospital bed, unable to get any rest the entire night. The ordinary hospital ward housed sixteen patients, one of whom was suffering from liver disease. Painkillers had no effect on him, and he would cry out in pain throughout the night. My mother repeatedly requested a transfer to another ward, but the hospital staff responded, “All the rooms are full. Please wait and see.”

That morning, Gu Zhengang and Zhang Baoshu came to visit my father in the ward. They exchanged pleasantries and asked about his condition. Despite having difficulty speaking due to his stroke, my father insisted on saying something. He struggled to get the words out:

“—I— blah blah — for three days—not working anymore—.”

He was trying to say that he had been in a coma for three days after his stroke and now couldn’t speak properly. The two high-ranking officials advised him to focus on his recovery before hurriedly departing. Zhang Baoshu, who hailed from the same hometown in Hebei, was serving as the Secretary-General of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) at the time. My father had worked alongside Gu Zhengang in the KMT’s Beiping office in his early years, but he had left the party long ago to dedicate himself fully to language education for decades. After their visit, the hospital transferred my father to a two-bed room.

This was my father’s second severe stroke. A year earlier, he had accompanied Professor Zhao Youpei on a tour across Taiwan to support language education in various elementary and middle schools. The work was exceptionally demanding: classroom observations, lectures, reviewing student essays, keynote speeches, and discussion panels filled every day. They were constantly rushing to catch trains, leaving no time to rest.

On one fateful day, my father gave two consecutive lectures, followed by a panel discussion. That evening, he met with teachers for consultations, staying up late into the night. By morning, he was unable to speak. The emergency doctor immediately administered two injections, and only then did his speech abilities begin to recover gradually.

After returning to Taipei to recover, my father’s speech abilities gradually returned to normal. Energetic as always, he couldn’t spend a moment idle and eagerly participated in northern Taiwan’s language education support activities.

One morning, he delivered a lecture at the Taipei Normal School. By noon, when he returned home for lunch, he began experiencing difficulty swallowing and slurred speech. A nap didn’t improve his condition. In the evening, we called a family doctor who was affiliated with the Mandarin Daily News. The doctor gave him an injection and noted his high blood pressure, advising him to get a good night’s sleep.

When morning came, my father woke up in bed, gesturing frantically and yelling incoherently. His left side was clearly paralyzed and powerless. At the time, Taiwan didn’t have 119 emergency ambulance services, so getting him to the hospital was a long and challenging ordeal. He was finally hospitalized for three weeks. Once his condition stabilized, he returned home to recover. Daily exercises became part of his routine, and over time, there was hope he might regain a certain level of health.

After three months, my father was largely able to take care of his daily needs independently, but he could never return to his former vibrant self, effortlessly engaging in witty conversations.

My mother often spoke to me about my father’s past, lamenting:

“It was all because of his love for public speaking. Your father just loved giving speeches. The energy he displayed on stage, the excitement, the ease—it was all fueled by the audience’s enthusiastic response. He simply couldn’t let it go. He’d lose track of time, completely ignoring his own health, and no one could stop him.”

Back then, my father’s speeches were indeed widely renowned. During his formal lectures, his voice was strong and resonant (this was before microphones were common), with a steady rhythm and clear pronunciation. His humor, ability to draw on a wide range of knowledge, and talent for explaining complex ideas in simple terms captivated his audiences. Sometimes, his jokes had the audience bursting into laughter, and when he spoke with great passion, his fervor swept through the room, drawing rounds of thunderous applause. Many people became devoted fans of Professor Wang’s speeches.

When my father traveled south to support language education, Principal An of Haiching High School in Kaohsiung was so captivated by his lectures that he followed my father’s schedule, attending every event in cities and counties across Kaohsiung just to hear him speak.

My father’s old friend, Uncle Wang Yuchuan, once said:

“When something is explained by Mr. Wang Fuqing, no matter how many times—ten times, even—people never tire of listening.”

Professor Liang Rongruo, a classmate of my father’s from Beijing Normal University and later his colleague in founding the Mandarin Daily News in Taiwan, wrote in an article:

“Shoukang had a generous heart and a strong build. He was candid, sincere, and always eager to help struggling friends and young people. He taught many students, and they could visit him anytime—early morning, noon, late at night, even on Sundays. Whether to discuss academics, careers, family life, or matters of the heart, he would always listen attentively and respond thoughtfully. ‘It is easy to find a teacher of knowledge, but hard to find a teacher of character.’ He was truly a rare teacher of character.”

Around a dozen students from the Mandarin Training Program at Beijing Normal University followed my father to Taiwan to promote Mandarin. He established the Mandarin Training Program at Taiwan Provincial Teachers’ University, where two graduating classes were dispatched to various middle schools to further language education.

Professor Fang Zushen, one of my father’s students, recalled:

“The thing that left the deepest impression on me in Mr. Wang Shoukang’s classes was his public speaking. Standing on stage, he wasn’t very tall but was solidly built, with a broad face and full cheeks. His hair was slightly balding on top but thick on the sides. Perched on the bridge of his nose were a pair of old-fashioned, round glasses with red and black frames. Behind the lenses, his eyes radiated strength, a mix of determination and kindness. One hand rested on the small of his back while the other gestured appropriately as he spoke.

He spoke with power and clarity, his voice resonating across a crowd of hundreds. His speeches, rich with profound insights and clever metaphors, frequently elicited laughter and thunderous applause.

I can honestly say that after hearing Mr. Wang’s speeches, I have never heard another speaker more outstanding than him.”

Mr. Zhong Lusheng, a graduate of the Mandarin Training Program at the Normal University, wrote an article titled “Full of Energy: My Impressions of Teacher Wang Fuqing”:

“Nine years ago, in our very first class with Teacher Wang Shoukang, he began by stating the two main objectives of the Mandarin Movement: ‘Unity of spoken and written language, and the unification of Mandarin.’ He recounted the past successes and failures of the movement. At times, he jumped with excitement; at other times, he hung his head in despair. Sometimes, he gritted his teeth in frustration; other times, he was overcome with sorrow.

You could see the light glimmering on his forehead, his trembling hands flying through the air, and his short, stout body swaying energetically as he spoke non-stop. At that moment, a surge of heat filled my chest, and I clenched my fists and gritted my teeth, caught up in his emotions. Glancing around at my classmates, every one of them was riveted, brimming with passion. We were deeply moved by his enthusiasm for language education and his extraordinary talent for public speaking!”

Zhong Lusheng continued, “Whenever I felt disheartened or defeated, I would invite two or three classmates to go see Teacher Wang for encouragement. After a session of his admonitions, I would leave feeling completely revitalized and all my doubts vanished! Every vein in his body seemed to be filled with heat, and every muscle packed with energy.

When Teacher Wang was bedridden, I went to visit him. I told him that we, his students, wanted to establish a grassroots organization to promote Mandarin. He repeatedly said, ‘Yes, yes!’ while gesturing enthusiastically. Finally, he managed to lift his thumb and utter the words, ‘Excellent work!’ I laughed and said, ‘You sound just like an American student speaking Mandarin.’”

After three months of recovery at home, the doctor deemed my father’s condition stable. However, whether he would ever regain the ability to speak remained uncertain. Continuous rehabilitation was the only option.

I really feel old now, often reflecting on events from many years ago: my father’s two severe strokes, the first of which he survived after emergency treatment, only to suffer a second, even more serious stroke a little over a year later. In those days, medical facilities and knowledge were limited, and he missed the golden window for effective treatment. This rare linguist—once Taiwan’s most captivating speaker, full of vitality and passion—lost his ability to speak forever.

Learning to speak again was probably the most excruciating ordeal of his life. Every afternoon, I would teach him to speak, one word at a time, like teaching a toddler. I would ask him to repeat each word after me. His pronunciation, tones, and even subtle nuances like soft tones and rhotacization were impeccable, but he couldn’t retain what he had learned. Everything he mastered one day was forgotten the next. His progress was slow and barely noticeable.

He could still read newspapers and recite them aloud, enunciating every word with precision, yet he couldn’t understand the meaning of the text. As a young person, I lacked patience, and after two months, my commitment to teaching him began to wane. From then on, he could only express himself with simple words, spending most of his time sitting silently in a wicker chair, gazing at the flowers and plants in the yard.

Aunt Xia (Lin Haiyin), our neighbor, once wrote:

“Mr. Fuqing fell ill due to a stroke, like many stroke patients, with one side of his body paralyzed and unable to speak. For Mr. Fuqing, a linguistics professor and a renowned speaker, this was an incredibly tragic blow. He initially stayed at the National Taiwan University Hospital, and after returning home, he diligently focused on recovery. Every afternoon, he would go out for a walk accompanied by a male helper.

At that time, Section 3 of Chongqing South Road had not yet been redeveloped, so the street was quiet, with few vehicles passing by. Every day, I would see him, wearing his long robe, hobbling along with one side of his body tilted, learning to walk with great effort.

When he reached our front door and saw it open, he would always come inside to check on the children. The kids were fond of him and warmly called out, ‘Uncle Wang! Come and sit.’ My youngest daughter played schoolteacher every day with the neighbor’s children. In the yard, they had a chair propped up with a small blackboard in front, and a few little girls sat below. My daughter, A-Wei, acted as the teacher:

‘Three, ㄙㄢ, first tone, three. Nine, ㄐ一ㄡ, third tone, nine… Uncle Wang, come, say it—nine, ㄐ一ㄡ, third tone, nine!’

Mr. Fuqing would move his lips, trying hard to open his mouth. ‘Eight!’ he would manage to say. He was thinking of saying nine, but it wouldn’t come out, and the word ‘eight’ emerged instead.

Poor Uncle Wang, left learning to speak every day with the little teacher.”

In the short term—two or three years, or perhaps even longer—my father was unable to work. It was likely he would never again stand on stage, passionately advocating for the great mission of “Mandarin unification and the alignment of spoken and written language.”

In 1959 Taiwan, there was no retirement system. Salaries for public servants and educators were meager, supplemented by monthly rations of essentials like oil, rice, and coal, just enough to scrape by. Living day-to-day without extra savings was a common reality. My mother, in poor health, had already quit her teaching job years earlier. My older brother had just graduated from university and was serving in the military in the south, while I was a junior in college. With our sole breadwinner bedridden, what were we going to do?

Sitting idly at home with my father, I would teach him a few simple everyday phrases. He would repeat after me, pronouncing each word flawlessly, but he’d forget everything he had learned shortly after. Sometimes, he would stare at the flowers in the yard, lost in thought, and suddenly blurt out to me:

“Hey, hey, us! —Starving—!” Then he would spread his hands in a helpless gesture.

“What are you talking about? That’ll never happen. You have two grown sons now.”

“What good are sons? Half-grown boys eat their fathers out of house and home.”

At that time in Taiwan, even university graduates in any field had almost no job prospects. My older brother, an outstanding student in the chemistry department at National Taiwan University (NTU), had received a full scholarship from the University of California, Berkeley, and planned to pursue his PhD across the Pacific after completing his military service. I, young and strong, felt I could do some kind of paying job—manual labor if necessary—since there wasn’t much to gain from my studies in NTU’s electrical engineering department anyway.

My mother remained calm and assured me repeatedly to focus on my studies and not worry about anything else—she would manage. Step by step, my brother and I graduated, completed our military service, went to study in the United States, earned our degrees, and secured jobs. We sent money back to Taiwan regularly, ensuring that our parents lived comfortably and had no financial worries.

But during those years when we were still studying in the United States and hadn’t started working, what arrangements did my mother make to get through those difficult times?

Many years later, after my father passed away, my mother came to stay with us in the U.S. for a while. In the quiet of the night, she would enjoy a couple of glasses of her special homemade liquor: ginseng and various medicinal herbs steeped in aged sorghum wine, forming a brownish, gelatinous substance. She would scoop a small amount, mix it with pure sorghum wine, and stir it evenly. The taste was potent, and after a few sips, she would recount those times in detail:

“Back then, your father always went out of his way to help his students—do you remember? The students from the Mandarin Training Program often came to our house to talk, sometimes for hours on end.”

“How could I forget? I especially remember Senior Brother Fang’s heartbreak. One rainy day, he came to our house completely drenched, looking utterly lost and barely able to speak. He said weakly to Dad, ‘Teacher Wang, I just hit her!’ Dad exclaimed in shock, ‘What happened? You shouldn’t hit anyone!’ Then Senior Brother Fang spent hours recounting the story of his failed romance.”

“Yes! Later, he found a suitable partner, settled down, and started his career. He’s now a well-known professor! After your father fell seriously ill, it was thanks to these good students of his. Sigh!”

At the time, Taiwan Normal University didn’t have a policy for retirement due to illness, and the Mandarin Daily News was already struggling as a private institution. They couldn’t provide much help. However, my father’s students—Zhang Xiaoyu, Fang Zushen, Wang Tianchang, Huang Zengyu, and Zhong Lusheng—had all earned qualifications as university lecturers a few years after graduation.

They reached an agreement with the university: since Professor Wang was ill and needed a period of rest, his basic language courses at Taiwan Normal University would be taught voluntarily by these lecturers. This allowed Professor Wang Shoukang to retain his faculty position.

I still remember Senior Brother Zhang Xiaoyu visiting our home every month, respectfully handing an envelope to my mother.

“But it wasn’t until 1964 that I found that job at IBM and started sending money home!”

“Exactly!” my mother said. “Xiaoyu and the others covered for your father’s classes for five years.”

Epilogue:

The years from 1959 to 1964 were the most challenging for our family. Senior Brother Zhang Xiaoyu quietly organized his fellow alumni to take turns teaching at Taiwan Normal University in place of my father, which sustained our family’s livelihood. My mother, believing that her two sons were too young to bear such immense pressure, kept the truth from us. She made sure we were sent abroad early, allowing us to focus on making a name for ourselves without worry. My brother and I, fortunately, did not disappoint her hopes and managed to establish ourselves across the Pacific.

More than 60 years passed in the blink of an eye. At a memorial event in Taipei, I met Professor Zhang Xiaoyu again. Now in his nineties, he remained sharp in both hearing and mind. Upon seeing me, he remarked:

“You still look just like you did as a child.”

I sincerely thanked him:

“If it weren’t for you and the other alumni volunteering to teach in my father’s place for five years, I truly don’t know what would have become of us!”

Senior Brother Zhang raised his head with a smile and replied:

“It was the right thing to do! Your father was our mentor. Back then, he cared so much for all of us. Let me tell you something: Teacher Wang assigned me to promote language education at the Kaohsiung City Education Bureau. The mayor at the time didn’t prioritize language education and sent me to teach at an elementary school instead. When Teacher Wang found out, he arranged for my transfer back to Taipei within a few days. He said Taiwan’s language education couldn’t afford delays—there was so much work waiting for me here.”

He reminisced enthusiastically, recounting past events, while I sat quietly, listening intently.

I truly feel old now, recalling a winter afternoon: my parents sat on the porch, basking in the sun. The sunlight illuminated my mother’s gray-white hair, thinning slightly at the top. My father gazed at her for a long time before motioning for me to lean down. I lowered my head, and in his usual loud voice, he said:

“Your mom—she’s balding.”

Each word was pronounced clearly and powerfully, without any trace of his previous speech impairment. My mother, overhearing him, was quite displeased and retorted:

“You’re the one who’s bald!”

Memories of my father continually swirl in my mind, compelling me to write something about him. Yet, the more I dwell on it, the harder it becomes to complete a piece. He taught us a nursery rhyme that went like this:

“Who’ll play with me? Strike a spark,

A spark flower sells melons—bitter melon,

Sell tofu—soft tofu,

Fry an egg—egg, egg shells,

Inside sits a brother,

Brother comes out to buy vegetables,

Inside sits a grandma,

Grandma comes out to burn incense,

Inside sits a young lady,

The young lady comes out to light the lamp—

Burns her nose and eyes.”

Singing it now, I can’t help but reflexively rub my hands over my nose and eyes, just like I did as a child.