A Little History of Pinyin

Author: Yun Wang

Chinese characters are often pictograms, which makes the biggest challenge in learning them the fact that the way they are written is unrelated to their pronunciation. In ancient China, recognizing characters relied entirely on reading thousands of books. Now, with the advent of Pinyin, it’s much more convenient. As long as you master Pinyin, you can read and recognize characters with the help of a dictionary.

Fanqie (反切)

Ancient Chinese dictionaries also had annotations for pronunciation. At that time, the method used for annotation was the fanqie technique, which employed two characters to indicate the pronunciation of another character. For example, in Xu Shen’s “Shuowen Jiezi,” the fanqie for “帝” (dì) was “都計切” (or: 都計反). The initials of the character being annotated match that of the first character in the fanqie (the initial of “帝” is the same as that of “都,” both being d), while the finals and tone of the annotated character match those of the second character in the fanqie (the rhyme and tone of “帝” is the same as that of “計,” both being i and in the fourth tone). This method is essentially just a form of annotation and could not possibly serve as a tool for literacy, because one must first grasp the correct pronunciations of a significant number of characters to read other characters. Moreover, many characters have multiple pronunciations, and some characters are pronounced differently in various regions.

Missionaries Were the First to Invent Pinyin

If we talk about the conscious use of letters to create a phonetic system for Chinese characters, it was indeed the foreigners, particularly missionaries, who paved the way. Almost without exception, they were missionaries whose primary motivation for inventing Pinyin was to facilitate their evangelizing efforts.

Matteo Ricci (Italian missionary, 1552-1610, also known as “Xitai,” “Qingtai,” “Xijiang”)

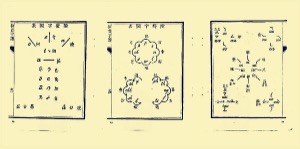

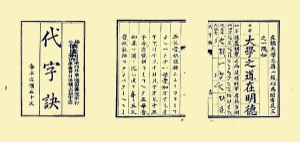

“The Miracle of Western Characters”: Latin Letters

In 1605, Italian missionary Matteo Ricci and Father Xu Guangqi compiled “The Miracle of Western Characters” (also known as “The Great Western Alphabet,” “Western Phonetic Dictionary for Chinese,” “Romanized Phonetic Articles of the Late Ming Dynasty”) using Latin letters to correspond with the sounds of Chinese characters. This system included twenty-six letters, forty-four finals, and five tones: flat, rising, departing, entering, and neutral. This was the first scheme in China to use Latin letters for Pinyin. Ricci’s original manuscript was reprinted in 1927 by Fu Jen Catholic University in Beijing from a copy preserved in the Wang family’s Ming Hui Lu.

Ming Dynasty’s European Art and Romanized Phonetics

Nicolas Trigault (French missionary, 1577-1628, also known as “Sih Biao”)

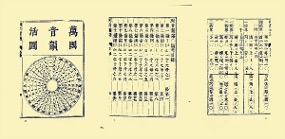

“Western Scholars’ Ears and Eyes”: Latin Alphabet

In 1626, French missionary Nicolas Trigault completed “Xi Ru Er Mu Zi” (Western Scholars’ Resources). This book is divided into three volumes: the first volume, “Introduction to Translation and Pronunciation,” serves as a general overview; the second volume, “List of Sound and Rhyme Tables,” is an index based on phonetics; the third volume, “List of Word and Sound Tables,” is based on characters to find phonetic pronunciations. Trigault created twenty-nine letters, consisting of five “self-resonant” vowels, twenty “co-resonant” consonants, and another four “non-resonant” consonants, which were used in other countries but not in China. Thus, the practical set includes twenty-five letters. This is the first phonetic radical dictionary, with its phonology based on the Nanjing dialect of the Ming dynasty.

“Western Scholars’ Ears and Eyes”: Latin Alphabet

Georgius Candidius (Dutch missionary, 1597-1647)

“Red-haired Characters”: Latin Letters, Xinguang Language and Other Indigenous Languages

In 1629, the Dutch pastor Georgius Candidius, while in Taiwan, translated the catechism into Xinguang (then a small tribe of the Siraya people, later known as Xinshi). He subsequently compiled a vocabulary for the Xinguang language, which led to the birth of the Romanized letters for Taiwanese. These Roman letters are not a new script but phonetic symbols for Chinese characters. Later, the Dutch created several dialectal symbols in Taiwan, collectively known as “Xinguang Script” or “Red-haired Characters.”

Elijah Coleman Bridgman (American missionary, 1801-1961)

“Selections of Chinese Literature in Cantonese Dialect”: Latin Letters, Cantonese

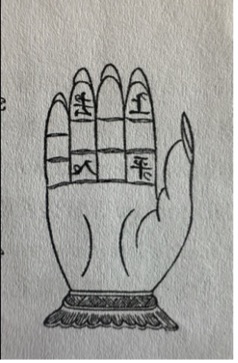

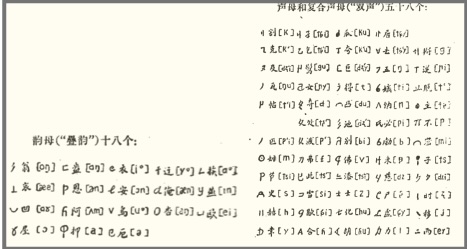

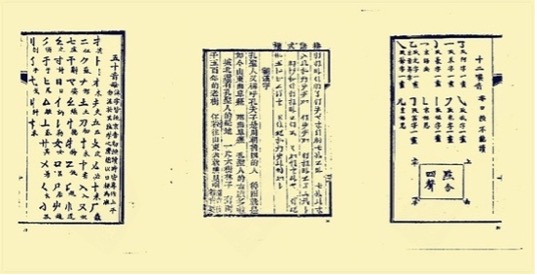

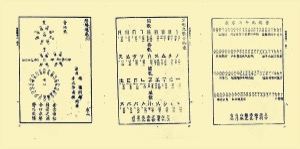

In 1841, the first American missionary to China, Elijah Bridgman, published “Selections of Chinese Literature in Cantonese Dialect.” He had three purposes for writing this book: 1) to help foreigners learn Cantonese; 2) to assist Chinese people in learning English; and 3) to demonstrate that phonetics can be used to read and write Cantonese. He explained that Cantonese has 15 sets of monophthongs and diphthongs, 18 consonants, includes aspiration markers and 8 tones, and considered the four positions of the palm’s edges as “level, rising, entering, and departing” tones (see image below).

Selections of Chinese Literature in Cantonese Dialect

John Van Nest Talmage (American missionary, 1819-1892)

“Elementary Studies in the Tang Language Character”: Latin Letters, Minnan

In 1852, “Elementary Studies in the Tang Language Character” was published. This was a textbook on vernacular writing compiled by Talmage and others, serving as a learning material for the orthography of Minnan language in Latin letters. The pastor from America, John Van Nest Talmage… The most precious 42 years of his life were dedicated to Xiamen. He discovered the phonetic rules of the Minnan dialect and tried to combine it with Latin letters to create a simple and easy-to-learn system of Minnan phonetic writing, resulting in a book. In addition, he also compiled a “Xiamen Sound Dictionary,” which was published in 1894. The Minnan phonetic writing laid the foundation for the phonetic movement among the Chinese.

The phonetic movement led by southern China

Missionaries were the creators of Chinese phonetics, and the earliest Chinese participants in phonetic practice had countless connections with them. This phase is referred to by later generations as the “phonetic movement period.”

Lu Gengzhang (from Tong’an, Fujian, 1854-1928, courtesy name Xueqiao

“Elementary Reader”: Variants of Latin letters (with a Latin letter comparison table); Xiamen pronunciation, Zhangzhou pronunciation, Quanzhou pronunciation.

| Lu Gengzhang studied English in Singapore. In 1892, utilizing the Romanized letters developed by missionaries, and after more than ten years of research, he selected 55 symbols and created a set of Romanized letters, naming it “China’s First Fast Phonetic New Characters,” and published the “Elementary Reader” in Xiamen. This book was the first self-created phonetic character scheme for spelling Chinese by the Chinese themselves, marking the beginning of the phonetic character movement. The “new phonetic characters” used in this book adopted 15 lowercase Latin letters: a, b, c, d, e, h, k, m, n, o, r, u, v, w, x, 3 uppercase letters: L, R, G, and 1 handwritten “S,” along with a Greek letter θ, in addition to a variant of near-Latin letters designed by himself (generally formed by combining three strokes | , c, and ɔ). The phonetic scheme used the traditional Chinese method of tone and rhyme dual spelling, consisting of three parts: “fifteen sounds” (initials), “letters” (non-nasal finals), and “nasal sounds” (nasal finals), using a total of 37 letters. The phonetic system is called “Xiamen tone,” and there are actually only 36 phonemes in the Xiamen sound system, with an additional 2 for Zhangzhou sounds and 7 for Quanzhou sounds; the rest are reserved for spelling other phonetic sounds. |

Lu Gengzhang’s “Elementary Reader”

Wu Jingheng (from Wujin, Jiangsu, 1865-1953, originally named Wu Tiao, Wu Zhihui)

“Sprout Letters” (also known as “Equal Rhyme Simplified Code”)

Title: A shorthand resembling bean sprouts; Changzhou-Wuxi dialect; double phonetic scheme

The “bean sprout alphabet” was invented by Wu Jingheng in 1895 and was taught in the Wuxi area between 1897 and 1898. This system has 18 finals, known as “overlapping finals,” and 58 initials and compound letters, with compound initials forming a double phonetic scheme. The system is also referred to as “Ten-Day Tong,” meaning “if there are ten days during which one cannot fully recognize it, there will be no such foolish person in the world;” it is also called “Thousand-Mile Teaching,” meaning “literature can only be disseminated within a thousand miles; beyond this, it must be corrected.” The original intention of the system’s creator was to facilitate literacy through phonetic notation.

Wu Jingheng’s “Bean Sprout Alphabet”

Cai Xiyong (from Longxi, Fujian, 1847-1898, courtesy name Yiruo)

“Chuan Yin Kuai Zi”: shorthand symbols, with added Latin letters for phonetic correspondence in 1905; spoken dialect; double phonetic scheme; includes numeric shorthand

Cai Xiyong entered the Tongwen Guan (a school for foreign students) at a young age and later served in the United States, Japan, and Peru. While stationed in Washington, he became aware of “the other country’s method of recording congressional debates and court arguments, which has been in practice for a long time. Delighted by its simplicity and speed, and concerned about the complexity of Chinese characters and widespread illiteracy, he referenced the shorthand by American Lindsley and integrated his own ideas with a focus on Mandarin phonetics, making adjustments to accommodate usage and compiled it into a single volume titled ‘Chuan Yin Kuai Zi,’ published in 1896.” His method divides the sounds into twenty-four tones using eight types of arcs and strokes of varying weight and direction, while thirty-two finals are determined using small arcs, small strokes, and dots. Combining sounds and finals forms a character using two strokes, while there are also instances of one stroke corresponding to one character. When discussing the origins of Chinese shorthand, Cai is undoubtedly considered a pioneer.

Cai Xiyong’s “Chuan Yin Kuai Zi”

Li Jie San (from Yongtai, Fujian, late Qing dynasty)

“Min Qiang Kuai Zi”: shorthand symbols; Chaozhou dialect

Li Jie San published a book titled “Min Qiang Kuai Zi” in 1896, which is based on the phonetic elements from the old Fuzhou tradition of “Qi Lin Ba Yin” and employs the structure of Cai Xiyong’s “Chuan Yin Kuai Zi.” It uses the method of eight types of arcs and arrows, incorporating the fifteen characters of the Qi military alphabet for sounds, using one stroke per sound, no further simplification possible; and employs lines, inches, circles, dots, horizontal, oblique, curved, and straight strokes for thirty-three finals, with one tone matching one final, and two strokes paired to form one sound. The writing method requires the use of grid paper divided into middle, left, and right sections.

- The six directions of ascending and descending are defined, with the fifteen coarser strokes as the primary strokes and the thirty-three finer strokes as secondary strokes. Identify the direction of the primary strokes: if it is slightly to the left and above, it represents a rising tone; if slightly left and slightly below, it represents a level tone; if it is directly in the middle and above, it represents a departing tone; if it is directly in the middle but slightly below, it represents an entering tone; if it is slightly to the right and above, it represents a lower departing tone; if it is slightly to the right and slightly below, it represents a lower entering tone. Aside from the same sounding rising tones, only the flat tone remains without a specific position, and it still follows the ancient method of circled positioning with dots to distinguish sounds.

Li Jie San’s “Min Dialect Quick Characters”

Shen Xue (from Jiangsu Wu County, courtesy name Juzhuang)

“Universal System”: shorthand symbols; Wu dialect; double spelling

Shen Xue was proficient in English and studied medicine at Shanghai Fanwangdu Academy. In 1896, he published “Universal System” in seven parts: the first part “Body and Use,” discussing the origin of phonology; the second part “Character Chart,” discussing ancient and modern character forms; the third part “Nature and Principle,” distinguishing the meaning of characters; the fourth part “Literature,” differentiating grammatical applications; the fifth part “Fanqie,” including the alphabet and fanqie tables; the sixth part “Calligraphy,” attaching a method for writing in Braille and so on; the final part aimed to use characters as a mechanism for understanding things, but the manuscript was not finalized. The original text was in English, titled “Universal System,” and was later translated into Classical Chinese, appearing in the August issues of “Shenbao” and “Shiwubao” in the twenty-second year of the Guangxu Emperor. This system also employed shorthand symbols as phonetic letters, and in terms of theory and writing, it demonstrated a certain level of creativity, being the first to classify words and employ connected writing of word classes. The author began writing this book at the age of nineteen, completed it in five years, and even personally went to tea houses to teach the community, but later died of poverty and hunger.

Shen Xue’s “Universal System”

Wang Bingyao (from Dongguan, Guangdong, courtesy name Yuchu)

“Phonetic Character Chart”: speed symbols (spelling phonetic letters); primarily Cantonese while incorporating phonetics from other provinces; double spelling

In 1897, Wang Bingyao compiled the “Phonetic Character Chart,” claiming, “This new phonetic spelling embodies natural sounds inherent to the characters. By uniting strokes to form characters, the first stroke opens up the sky as a phonetic mother, whether in vertical, horizontal, diagonal, or folded formations, or through combinations and variations to create vowel sounds; by operating an image to represent Taiji, or through vertical, horizontal, or cross examinations, due to varying forms, results in the sound mother of quick writing. Combining the sound mother and vowel to form characters, and organizing sounds and tones…” The languages of the eighteen provinces are characterized by simple characters and comprehensive expressions. What is the nature of this? The Guangdong East phonetic inventory consists of fifty-four phonemes, while other provinces may add or subtract from this number. Excluding reductions and additions, there are twenty phonemes in the northern dialect, with ten each in the Fuzhou and Hakka dialects. Therefore, the languages of the eighteen provinces can be summarized to about ninety-four phonemes and thirty initials, totaling one hundred twenty-four characters. This represents a comprehensive capture of the spoken languages in China. The innovation of this plan lies in its early establishment of a phonetic code for reforms in telegraphy using four-character Chinese, as well as the development of flag signals and light codes based on this phonetic system.

Wang Bingyao’s “Pinyin Alphabet”

The simplification movement that arose in Northern China

The phonetic movement focused on Latin-based phonetics and shorthand symbols, primarily concentrated in regions active with Min and Cantonese missionary activity, and failed to become mainstream. However, the “Simplified Character Movement,” which emerged in Northern China in the early twentieth century, had a relatively wider influence.

Wang Zhao (from Ninghe County, Zhili Province, now Ninghe District, Tianjin City, 1859-1933, courtesy name Xiaohang, pseudonym Luzhongqiongshi, and also known as Shuizhong)

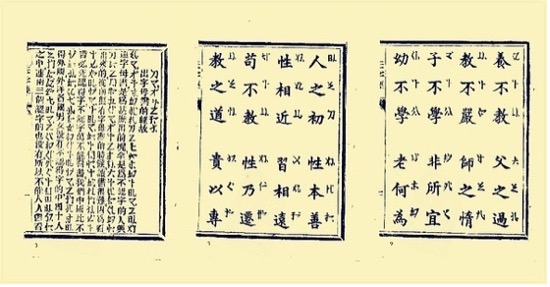

“Phonetic Alphabet of Mandarin”: stroke components of Chinese characters; Mandarin phonetics; double spelling; later represented with symbols for cursive writing

Wang Zhao served in the Qing government and fled to Japan due to his involvement in the Hundred Days’ Reform. While in Japan, he emulated the Japanese kana, using components or parts of Chinese characters to develop a phonetic scheme for Chinese characters. In 1900, he published the “Phonetic Alphabet of Mandarin” in Tianjin, and his students, including Wang Pu, opened training classes in Beijing to spread it. Wang Zhao devoted himself to seeking official recognition for his invention, but due to the changing political situation, he never achieved his goal. Nevertheless, through training classes and the establishment of newspapers, he managed to widely disseminate the “Complete Phonetic Alphabet of Mandarin” in Northern China.

“The Phonetic Alphabet of Mandarin” and its reading materials

Lao Naixuan (from Tongxiang, Jiaxing Prefecture, Zhejiang Province, 1843-1921, courtesy name Jixuan, pseudonyms Yuchu and Rensou)

“Record of Simplified Characters”: strokes of Chinese characters; Nanjing pronunciation; double spelling; later represented with symbols for cursive writing

Because Wang Zhao’s “Mandarin Alphabet” was limited to the Beijing accent, it, although popular in the north, could not be promoted in southern provinces. Therefore, in 1905, Lao Naixuan used the original scheme of “Mandarin Alphabet” as a basis and supplemented it with six initials and three phonemes. Once the phonetic symbols were established, a volume titled “Revised Simplified Phonetic Notation” (i.e., “Ning Phonetic Notation”) was created to encompass the phonetics of the Ning influential region, including parts of Anhui. At that time, the simplified character school established by Governor Zhou Fu of the Liangjiang region used the “Ning Phonetic Notation” as its textbook. Over a span of two years, hundreds of students graduated; those who were particularly bright could speak Mandarin indistinguishably from natives of Beijing. After Duan Fang succeeded Zhou Fu as the governor of Liangjiang, he mandated that all forty primary schools in Jiangning incorporate a subject on simplified characters. As a result, women and villagers who had been illiterate suddenly found themselves able to read newspapers and write letters—like the blind suddenly seeing a clear sky. The extent of this achievement can only be imagined.

Lao Naixuan’s “Simplified Phonetic Notation”

Liu Shien

“Phonetic Notation”: Self-created symbols; Mandarin phonetics; a trigraph system in a double-pinyin format; additional symbols indicate joined writing.

This book was written in 1909, with twenty-five “initials,” twenty-one “finals,” and three “medials.” Except for “si,” “shi,” “ci,” and “chi,” the initials and finals share the same symbols. The method of tone marking is unique to various schools. Liu stated: “If the initial is inside and the final is outside in the formation, it represents the level tone; if the initial is above and the final is below, it represents the rising tone; if the initial is on the left and the final is on the right, it represents the departing tone; when combined vertically, and the medial is attached to the final, it represents the lower level tone; when combined horizontally, and the medial is attached to the final, it represents the entering tone. Thus, even with the initials and finals having the same symbol, without additional dots or markings for the level, rising, departing, and entering tones, they can still be clearly distinguished without confusion—this almost perfectly suits the phonetic symbols of our country.”

Liu Shien’s “Phonetic Notation”

Jiang Kanghu (from Yiyang, Jiangxi, 1883-1954, originally named Jiang Shaoquan)

“Tongzi”: English letters; Mandarin sounds but can be used to spell regional dialects;

The “Tongzi” is a long-lost proposal among the Qing dynasty’s phonetic systems. Jiang Khanghu believed that the phonetic letters in Mandarin lacked entering tone characters, southern dialects, and regional pronunciations, making the phonetics incomplete. His “Tongzi” categorized initials, finals, and compound finals, translating them into the twenty-six English letters, with additional rhyme symbols (i.e., tone markers). Jiang believed that his “Tongzi” was easier and more convenient than Lao Naixuan’s “Simplified Phonetic Characters” and Wang Zhao’s “Mandarin Letters.”

Jiang Kanghu’s “Tong Word”

During this stage, various pinyin schemes emerged like bamboo shoots after rain, diverse and abundant in form. In addition to the aforementioned schemes, there are several other categories:

-

Strokes Category

Tian Tingjun

“Pinyin Substitution Method”: Chinese character strokes (with Latin letters corresponding); Hubei dialect; an incomplete three-sound system, partially double-sound.

Published in 1906, “Pinyin Substitution Method” has a total of nineteen “father sounds” (initial consonants) and thirty-two “mother sounds” (finals); out of these thirty-two “mother sounds,” half are “single mother sounds” (represented by single letters), and half are “double mother sounds” (represented by double letters), so only thirty-five letters are actually in use. These thirty-five letters are derived from the strokes of Chinese characters. This scheme is half a step ahead of the double-sound system, having partially entered the three-sound system; unlike phonetic symbols, it is a half step behind the three-sound system, as some finals still retain remnants of the double-sound system.

Tian Tingjun’s “Pinyin Substitution Method”

Zhang Binglin (from Yuhang, Zhejiang, 1869-1936, originally named Xuecheng, also known as Taiyan, courtesy name Meishu)

“Refuting the Proposal to Use Esperanto in China”: Strokes (single ancient characters); double-sound.

Between 1908 and 1910, during the publication period of “New Century,” run by Chinese students studying in France in Paris, several anarchists proposed that China should abolish Chinese characters and the Chinese language, instead using “Universal New Language” (Esperanto). Zhang Taiyan disagreed with this naive and extreme proposition, and also had different opinions on the sound-based characters at the time. Therefore, he wrote this article to refute the fallacies of the anarchists while also presenting his views on sound-based characters. He published his proposed system of sound-based characters formed by “extracting and simplifying the shapes of ancient texts” — “Niuwen” and “Yunwen,” which became the precursor to the later “Bopomofo” scheme.

Zhang Taiyan’s “Refuting the Proposal to Use Esperanto in China”

Zheng Donghu

“Instructions on Sound-based Characters” (see below): Chinese character strokes; double-sound.

This is the stroke-based sound character scheme published by Zheng Donghu in 1910, also at the end of the Qing Dynasty… The last type of phonetic character scheme.

Zheng Donghu’s ‘Phonetic Character Manual’

The stroke-based schemes also include “Dai Sheng Shu” by Li Yuanxun (courtesy name Wuqiao) from Henan and “Hanwen Yin He Jianyi Shuzi Fa” by Huang Xubai (courtesy name Zhi Xiang).

- Numeric Type

Yang Qiong (from Dali, Yunnan, courtesy name Ling Lou), Li Wenzhi (from Dali, Yunnan, courtesy name Nan Bin)

“Xing Sheng Tong”: Similar to numeric strokes of Chinese characters

The “Xing Sheng Tong,” co-authored by Yang Qiong and Li Wenzhi in 1906, uses Chinese character strokes as phonetic symbols, somewhat resembling numbers. They state, “This book takes twenty-four characters as phonetic fathers, twenty characters as phonetic mothers, utilizes the principles of harmony and concentrations as the four matrices, utilizes long and short sounds as the four ropes, utilizes the five rules of Gong, Shang, Jiao, Zheng, Yu, and utilizes the four standards of rising and falling.” As for “the essence of form boils down to Yin and Yang: one produces two, and both Yin and Yang are included; two produces four, and all things arise. What is the one? In form, it is represented as •, drawn from • to represent one, from • to represent 〡, from • to represent 丿; this is what is called producing two. Combining •, 〡, and 丿 yields four entities, which we further examine through balance, documenting them with figures. Hence, we obtain twenty-four positive forms and twenty negative forms, with Yang forming the foundation and Yin forming the lateral; thus acquiring four hundred eighty, multiplying by four entities results in one thousand nine hundred twenty, and through an additional four multiplications, we obtain a total of seven thousand six hundred eighty, thereby completing the shapes.”

Yang Qiong and Li Wenzhi’s ‘Xing Sheng Tong’

- Latin Alphabet Type

Zhu Wenxiong (from Kunshan, Suzhou, 1883-1961)

“Jiangsu New Letters”: Latin letters (including five inverted letters and one horizontal letter); Wu pronunciation; phoneme system

In the preface of the original book “Jiangsu New Letters,” published by Zhu Wenxiong in 1906, it states: “I believe that instead of creating new characters that the world has never seen, it is better to adopt characters that are universally recognized. Therefore, I have adopted the European letters, retaining their original pronunciations or altering them, while also creating six additional characters to fill the gaps. In total, there are thirty-two letters, two altered sounds, eleven compound sounds, and nine familiar sounds. The altered sounds are denoted by dots, the compound sounds form a single sound from two vowels, and the familiar sounds form a single sound from two falling tones. We study the rhymes above and use fanqie below, while also referencing Roman and English phonetic spellings to create a new writing system.” The six characters created by Zhu are the inverted e, and Here is the English translation of the provided text:

“r, t, f, l, and horizontal c, what they represent by double sounds refers to diphthongs, and the so-called熟音 refers to the sounds marked by double consonants. As for the method of tone marking, Zhu already knew how to use letters and avoid additional symbols.

Zhu Wenxiong’s ‘Jiangsu New Alphabet’

Liu Mengyang (from Tianjin, 1877-1943, courtesy name Bonian)

‘Chinese Phonetic Alphabet Dictionary’: Latin letters; Mandarin sounds; phoneme rules; parts of compound words connected by short horizontal lines

The original preface of the ‘Chinese Phonetic Alphabet Dictionary’ published in 1908 states, “There are twenty-six phonetic symbols. Among them, ten are primary sounds, twenty-one are secondary sounds, seven are compound primary sounds, twenty-nine are auxiliary secondary sounds, and five are half primary and half secondary sounds. Regardless of whether it is Chinese or foreign languages, whether it is the phonetics of Chinese characters or foreign letter phonetics, all can be found within.” Also, it states, “All primary sounds in the letters are pronounced as Yinping (level tone). Words in the Yinping tone do not need tone marks. However, for words in the Yangping (rising tone), Shang (upper tone), Qu (falling tone), and Ru (entering tone), tone marks must be added to the primary sound at the end of the words.” The so-called tone marks are as follows: Yangping (´), Shang (¯), Qu (ˋ), Ru (ˆ).

Liu Mengyang’s ‘Chinese Phonetic Book’

Fourth, in other forms, there are characters resembling Manchu script, such as Ma Ti Gan’s ‘Chuan Yin Zi Biao’ and ‘Latest Yue Fu Zi Biao’ from Linqu, Hebei (Sanhe); and those resembling musical notes, such as Zheng Zhenling’s ‘Simple New Characters’ from Xiangshan, Guangdong, etc.

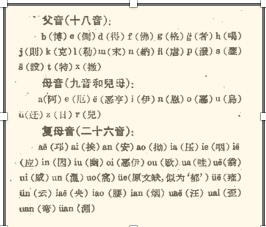

Introduction of Zhuyin Symbols

In 1913, the Republic of China held a meeting of the Pronunciation Unification Association, where there was heated debate over what kind of pinyin to use. At that time, there were mainly three factions: the “Radical Faction” represented by Wang Zhao and others; the “Symbol Faction” represented by Ma Ti Gan and others; and the Roman Alphabet Faction represented by Wu Jingheng and others. As a result, the representatives from Zhejiang, relying on their numbers and with proposals from Ma Yuzhao, Zhu Xizu, Xu Shouchang, Qian Daosun, Zhou Shuren, and others, passed the “Phonetic Alphabet” for temporary use in determining pronunciation, which was initially proposed by their teacher Zhang Binglin in his work ‘Refuting the Use of a Universal Language in China’. After revisions, it was confirmed to be 39 letters, officially issued by the Ministry of Education in 1918. In 1920, the number of Zhuyin letters increased to 40. In 1930, the Zhuyin letters were renamed “Zhuyin Symbols.” The phonetic symbols are still in use in Taiwan.

The Introduction of Mandarin Romanization

In 1923, the fifth regular meeting of the Preparatory Committee for the Standardization of Mandarin in the Republic of China decided to form the “Mandarin Romanization Committee.” Several key members of the committee, including Zhao Yuanren, Liu Banong, Li Jinxie, Qian Xuantong, Lin Yutang, and Wang Yi, formed a group known as the “Several People’s Committee.” From September 1925, they dedicated an entire year to researching Mandarin Romanization, which was announced by the Academia Sinica in 1928 and named the “Mandarin Romanization Phonetic Method,” utilizing 26 standard Latin letters. Thus, there were two systems for Mandarin phonetics: one was the Zhuyin Fuhao (Bopomofo) and the other was the Mandarin Romanization Phonetic Method, and both were used concurrently. In 1940, the Ministry of Education’s Mandarin Promotion Committee resolved to rename the “Mandarin Romanization Phonetic Method” to “Transliteration Symbols.” Zhuyin Fuhao, derived from Chinese characters, was generally easier for illiterate citizens to accept, while Mandarin Romanization also played an irreplaceable role in fields such as telegraphs. Various dictionaries published during this period adopted both systems of phonetics.

Mandarin Phonetic Alphabet announced by the Academia Sinica in 1928

Modern Chinese Pinyin Ultimately Becomes the Tool for Chinese Characters in Mainland China

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, efforts were immediately made to develop a Pinyin scheme and to replace Chinese characters with phonetic scripts. A civil organization called the “Chinese Character Reform Association” set up a “Pinyin Scheme Research Committee” to discuss which letters should be used in the Pinyin scheme. In October 1955, a national conference on character reform was held in Beijing, where representatives were presented with six Pinyin schemes: four were based on the brush strokes of Chinese characters, one was Latin alphabet-based, and one was Slavonic alphabet-based. Ultimately, Mao Zedong agreed to adopt the Latin alphabet scheme, which was approved at a central meeting. Over the years of discussions on the Chinese Pinyin scheme, various plans were designed totaling more than 3,300, making this scheme regarded as a product of collective wisdom. In February 1956, the Character Reform Committee published the “Chinese Pinyin Scheme (Draft)” and publicly solicited opinions. This draft contained 31 letters. In February 1958, the first session of the Fifth National People’s Congress officially passed the “Chinese Pinyin Scheme,” which used 26 letters. After this scheme was adopted,

“Zhuyin Fuhao” and “Guoyu Luomazi” have been used in conjunction with Mandarin in mainland China to this day.

Modern Chinese Pinyin and Zhuyin Comparison Table

It has been 500 years since Matteo Ricci invented the first Chinese phonetic system. The development of Chinese phonetics has not made significant progress since then. Aside from eradicating illiteracy, Pinyin has not achieved the goal of truly connecting sounds and meanings, nor has it integrated with the world, to seamlessly integrate political, legal, religious, economic, and technological vocabulary — which is lacking in the Chinese language — into the Mandarin language system, which aligns perfectly with China’s thousands of years of being confined within a feudal mindset. All changes are either mixed with personal preferences or reflect the personal will of rulers. We find that the Latinization movement on the left is not mentioned at all in Li Jinxu’s “Overview of the Guoyu Movement” published in 1935, while books related to the Guoyu movement on the mainland after 1949 have almost completely erased the right-wing-led Guoyu movement. Such an attitude, when it comes to the academic issue of language and script, cannot help but be seen as a tragedy.

References:

“Historical Materials of the Guoyu Movement in Taiwan” edited by Zhang Boyu, Taiwan Commercial Press (1974)

“Connecting Sounds to Meaning” by Wang Dongjie, Beijing Normal University Press Group (2019)

“Overview of the Guoyu Movement” by Li Jinxu, Commercial Press (2011)

“Discussion Collection of the Draft Plan for Chinese Phonetics” by Script Reform Press (1957)

“Essentials of Ancient Rhyme Studies” by Li Xinkui

“Chinese Modern Language Planning: Theory and Practice” by Gao Wuzhi

“History of the Evolution of Chinese Pinyin Letters” by Luo Changpei