The National Language Movement and Popular Education

Author: Yun Wang

In the early years of the Republic of China, illiteracy was a serious social issue. Illiteracy, simply put, refers to people who cannot read or write. As a result of being illiterate, these individuals inevitably become “politically blind,” “economically blind,” “self-defense blind,” and “socially blind.” When illiteracy becomes the dominant group in society, it will “destroy countless talents, increase economic poverty, hinder political democracy, lead to miseducation passed on to future generations, promote national decline, slow down cultural progress, invite foreign humiliation, and exacerbate global turmoil.” In 1901, Emperor Guangxu abolished the imperial examination system and promoted the establishment of schools, placing emphasis on literacy education. In the same year, the Ministry of Education under Emperor Xuantong published simplified literacy school regulations and basic literacy textbooks, but before they could be implemented, the Qing government fell. With the establishment of the Republic of China, the National Language Movement emerged, with the initial intention of enlightening the public. The introduction of phonetic symbols and the unification of the national language made literacy campaigns and universal education feasible, marking the beginning of popular education. However, due to the turbulence of the Beiyang government, many initiatives only existed in name and had little substance.

Implementing popular education is far more complex than ordinary education. Firstly, there is a lack of qualified teachers. At the dawn of modern education, the standard for the national language had just been established, and well-educated and trained teachers were scarce. In traditional Chinese thought, rulers held the idea that “the people can be made to follow, but not to know.” The goal of education for ordinary people was to become “scholars,” who were considered superior beings. The focus on educating the common laborer was looked down upon by the cultured individuals of traditional society. Secondly, most ordinary schools evolved from private tutoring or study halls, while popular education lacked any available platforms to utilize.

At that time, in cities like Beijing, which had a high level of education, developed culture, and progressive thought, many popular educational institutions such as community schools, night schools, tutoring classes, and training organizations emerged. These institutions were often free and primarily supported by voluntary student efforts and schools, with teachers often being college and high school students or educators. For instance, my grandfather Wang Shuda worked in such positions during his studies at Beijing Normal University from 1919 to 1928, and his classmates took pride in being able to participate in these activities. In their minds, “Education is our divine duty.” “The school is our duty.” It should be noted that Beijing Normal University, particularly the Chinese Department, played a significant role in popular education. They were influenced by the teachings and examples set by teachers like Qian Xuantong and Li Jinxi, and they were imbued with a sense of responsibility to “serve society” as was expected of normal school students at that time. Wang Shoukang, who graduated from the Chinese Department of Beijing Normal University in 1925, served in the military during both the Northern Expedition and the War of Resistance. With his wife and children, he traveled to and fro with the singular purpose of teaching illiterate soldiers to read. Following the methods taught by his teacher Li Jinxi, he compiled a set of “New Recruit Literacy Textbooks,” first teaching new soldiers to memorize 37 phonetic symbols and learn pinyin, and then teaching them to recognize characters, with phonetic symbols accompanying each character to aid pronunciation. In just a few months, the new recruits achieved notable literacy results, able to speak Mandarin clearly, so much so that their commander applied to have his officers join Wang’s literacy classes. Although few normal students served in the military, there were many who earnestly taught civilian populations.

In fact, during the Republic of China era, there were not many successful systems of popular education, with Shandong and Dingxian in Hebei being the most noteworthy.

In 1931, Dong Weichuan, a graduate of the Chinese Department at Beijing Normal University, was invited by He Siyuan to serve as the Supervisor of the Shandong Education Department and concurrently as the Director of the Shandong Provincial Education Museum. When he took office, the Education Museum faced serious internal and external challenges. Internally, there were outdated facilities, lack of funding, chaotic operations, and a lack of staff motivation; externally, society held a misunderstanding of the popular education institution, with many equating it to an old-age home, a wasteful organization, or an unemployment office. However, through the efforts of Dong Weichuan and his more than thirty colleagues, everything improved significantly. According to the 1934 publication “Jinan Daguang,” the Education Museum showcased exhibits on natural history, hygiene, botany, minerals, and art, as well as domestic goods, provincial products, children’s toys, and various books, all for free viewing. The popular education institution also established schools for the public, adult classes, a literacy training class, a public inquiry center for characters, and a writing service for the public. Additionally, more than ten publications were produced, including the “Weekly of Popular Education (Phonetic Version),” “Shandong Farmer’s Report,” and “Popular Weekly,” among others. The “Shandong Farmer’s Report” was praised by the Mandarin Society as the most standardized publication, utilizing horizontal writing, continuous wording, phonetic annotations for each word, and tone markings. The Shandong educational… The reason why the education center has been able to gain significant momentum is related to Dong Weichuan’s literacy promotion philosophy. The goal of literacy promotion is to be able to read and write, but sometimes it cannot start or end solely with literacy. First, ordinary people experience life pressures, and they would be more interested in literacy if it could help them in their daily lives. The various professional exhibitions and training at the education center provide them with practical assistance. Second, if people learn to read but do not apply it, they will quickly forget it, so the education center has published more than ten types of publications. These materials are rich in content, easy to understand, and some even include phonetic notation, making it easier for readers of different levels to comprehend. Third, adhering to the idea of serving the public, the education center offers functions such as “word inquiry” and “ghostwriting,” which are practices that gain public recognition, acceptance, and dissemination. Fourth, as professionals in education, Dong Weichuan and his team also need feedback from various attempts to complete the process of educational experimentation.

Here’s a successful example: back then, the education center conducted an experimental area in Zhudian Township, about ten miles from Jinan, with an initial three-year plan. The plan consisted of promoting literacy through community schools in the first year, improving production through cooperatives in the second year, and engaging in various forms of self-governance and political education in the third year, based on the first two phases. However, the local people did not accept this plan; they were skeptical of the office, thinking it was a tax bureau or government office. Even when they put on plays and movies to promote the benefits of literacy and informed people that there were community schools available, they not only showed no enthusiasm but were also unwilling to lend their houses or furniture, fearing that they would be asked for money if they entered. The school could not be established, so they had to advance the second year’s work and start with the cooperatives. Initially, the farmers were also skeptical until they were introduced to successful cases of borrowing money from banks at low interest rates. Although each member only borrowed a few dozen yuan, they were overjoyed. As a result, the farmers immediately regarded the person who helped them establish the cooperatives as a compassionate figure, akin to Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy. Six months later, they not only benefited materially from the cooperatives but also received a form of education, gradually developing a conscious desire to become literate. When the cooperatives distributed their surplus, the farmers even proposed to allocate a portion of the interest to fund adult and children’s classes, and they could borrow rooms and tables and chairs. In this way, a school was established in each of the five villages without the need for recruitment; the directors of the cooperative gathered the students together, and women also participated. Subsequently, matters such as inoculation, settling disputes, abstaining from gambling, improving agriculture and handicrafts, and electing village leaders were smoothly carried out.

Involved in the practical process led by Dong Weichuan were his wife, Kong Wenzhen, and his sister-in-law, Kong Fan Jun, along with his brother-in-law, Xiao Jialin. Kong Wenzhen graduated from Beijing Women’s Normal University, and Xiao Jialin graduated from the Chinese Department of Beijing Normal University, two years ahead of Dong Weichuan. At this time, he was working in the Ministry of Education, serving as a member of the Committee for the Unification of the National Language, the head of the People’s Dictionary Section at the Chinese Dictionary Editing Office, a principal writer for the “National Language Weekly,” the president of the Promoting Society for Romanization of the National Language, and the editor of the “National Language Romanization Weekly.” His wife, Kong Fan Jun, was also an editor at the Chinese Dictionary Editing Office and had published folkloric books such as “Games for Children in the Republic of China” and “Children’s Games in Shandong.” It is no wonder that a provincial education center was able to publish so many professional publications at once! Investigations by the Committee for the Unification of the National Language showed that the Shandong Provincial People’s Education Institute was the earliest and most thorough in its improvements regarding national language reading materials.

To further enhance the educational level, from 1934 to 1935, with funding from the Nationalist Government, Dong Weichuan and his wife traveled to Europe to study social education. Unfortunately, the war broke out in 1937, and by the end of that year, the Kuomintang government in Shandong fled Jinan. In December, Dong Weichuan and his colleagues also escaped south, and the People’s Education Institute was taken over by the Japanese puppet Shandong government. In 1939, the Japanese transformed it into the Provincial New People’s Education Institute. It turned out that the Japanese were also vying for this territory.

Dong Weichuan did not stop there. As the head of the first Social Education Work Team of the Ministry of Education, he led workers in promoting anti-Japanese efforts, popularizing education, and eliminating illiteracy across some regions in Sichuan, Hubei, Hunan, and Guizhou provinces. During this time, he served as the director of the People’s Education Institute in Nanchong, Sichuan. In 1941, he participated in the establishment of the National Social Education College. At that time, the National Government placed great importance on civilian education, and despite tight wartime funding, they still established a college dedicated to researching civilian education and training relevant professionals. Civilian education finally entered the mainstream. Xiao Jialin also joined the college, becoming the second director of the National Language Specialized Program.

Dong Weichuan and Kong Wenzhen couple in Europe

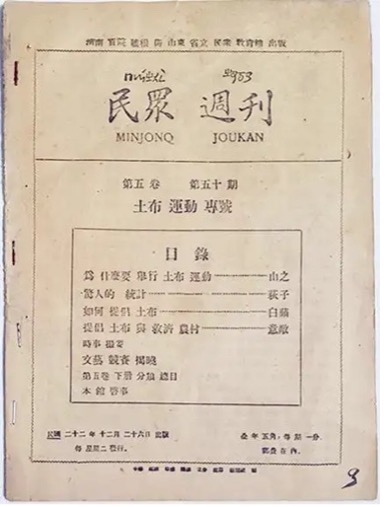

Magazine published by the Shandong Provincial Education Bureau

If the strength of the Shandong Folk Education Institute lies in its reading materials, then the advantage of the People’s Education Promotion Association’s experimental zone in Ding County, Hebei lies in its teaching methods. The language teaching experiment in Ding County began relatively early. In 1923, Li Jinhui, a special envoy from the Ministry of Education, came to promote the national language education. In 1930, Zhao Yuanren also came to implement adult education, and by 1934, it was confirmed that the illiteracy eradication phase could be shortened to three months, all thanks to the teaching methods.

Mr. Yan Yangchu, the secretary-general of the People’s Education Association, was a foreign PhD who had returned from the United States and was the director of the Ding County experiment. He gathered scholars including Qu Junong, Sun Fuyuan, Zhao Shuicheng, and Zhao Jiliang to discuss and research teaching methods for phonetic symbols to make it easier for students to grasp. Li Jinshu, then the director of the Ministry of Education’s school education division, participated in this and sought the opinions of Li Jinxu, Qian Xuandong, and others. After the new methods were implemented in the experimental school in Nanjicun Village, they found that students could read folk literature, such as “Little Aunt Xian” and “Su Mei Shan Sells His Wife,” after learning phonetic symbols. There were no unfamiliar characters or mispronunciations, astonishing everyone in the village. Later, the students even began to write diaries, using phonetic symbols for the characters they didn’t know, and were able to articulate everything they wanted to express. The conclusion drawn from this experiment was that phonetic symbols were learnable and desirable for farmers, and they must be taught from the beginning of the school year.

The People’s Literature Department of the People’s Education Promotion Association also compiled the “Common Vocabulary for Farmers.” As long as students were taught to connect words when writing, it was easy to understand sentences. Thus, although they only studied for a few months, their capabilities matched those of people who had studied for several years before. In the experimental school in Dongzhugu Village, more than half of the students could read long stories by the seventh week after the school opened, though the texts had undergone some transformation. The practice of folk education in Ding County not only eliminated illiteracy but also summarized valuable experiences. It turned out that the difficulty of teaching Chinese characters did not lie with the teachers or learners; rather, the rationalization of Chinese characters was key.

In the national language movement, Peking University and Beijing Normal University became the leading forces. The grassroots promotion relies on those who take education as their mission and believe in the national language. According to the Ministry of Education’s “National Statistics on Social Education undertakings” from 1930, there were 29,302 popular schools, 2,838 literacy centers, 2,308 public lecture venues, 12,949 public reading places, and 10,609 inquiry and writing assistance centers, totaling 60,000 facilities, with a budget of over 2.4 million yuan and 80,000 staff members. Although this number is not small, the effectiveness was minimal. The aforementioned Shandong and Ding County were the most successful, and this success largely depended on the implementers.

References:

“China’s Illiteracy Problem” edited by Dong Weichuan, Zhonghua Book Company, 1948

“A Decade of Turmoil and a Stubborn Boy” by Wang Zhengfang, Beijing Publishing Group’s Beijing October Literature and Art Publishing House, 2018

“Outline of the History of the National Language Movement” by Li Jinxu, Commercial Press, 2011

“National Beijing Normal University Alumni Directory, 17th Year of the Republic” Beijing Printing Bureau, 1928