The talented young man Bai Dizhou in the National Language Movement

Author: Yun Wang

Defining Bai Dizhou as a young talent in the Mandarin movement could not be more appropriate—he eternally remains at the handsome age of 34. His death can be considered the most painful loss in the Mandarin movement. It’s no wonder that Qian Xuantong lamented upon hearing the news of his passing, saying: “The young perish while the old survive, the strong die young while the sick endure… Truly, the Mandarin community is unfortunate!”

Lao She was a close friend of Bai Dizhou. In “Crying for Bai Dizhou,” he wrote: “On October 12, I received a telegram: ‘Dizhou is critically ill.’ I set out on the 14th; by the time I arrived in Beiping, he had already passed… It all felt like a dream. In late August, the three of us—Dizhou, Tie Hen, and I—were still in Nanjing together. How joyous it was! Dizhou was busy arranging for us to visit various places and insisted on accompanying me to Shanghai, but I stopped him. He first went to the Northwest with Mr. Liu Banong; after Banong’s death, he traveled to Xi’an to teach. He ran from Xi’an to Nanjing, still wanting to go to Shanghai with me. I didn’t ask him to go. His health was indeed good, but running around in such hot weather isn’t just for fun. This was my small concern; I never dreamed that he would die… Dizhou, Dizhou, we can only cry; it is useless, indeed useless. However, we are crying for your worth. We can find someone more handsome than you, someone with more knowledge than you, someone with higher thoughts than you; but where can we find a ‘friend’ like you?” In the following period, Lao She became so overwhelmed with sadness that he couldn’t do anything.

The day after Bai Dizhou passed away, the “Dizhou Family Aftermath Committee” was established in Zhonghai, consisting of the five permanent members of the Mandarin Society, his second wife Xu Rong, his brother Bai Wenyuan, as well as his close friends Luo Changpei, He Rong, Shu Sheyu, and Liu Tiehen. On November 11, the Mandarin Society held a memorial service for Bai Dizhou, hosted by Li Jinxie, with a eulogy delivered by Qian Xuantong. Wei Jiangong, Luo Changpei, and others published commemorative articles. So, what kind of young comrade was Bai Dizhou that left everyone reminiscing so fondly?

Bai Dizhou, born Bai Zhenying, was a native of Beiping with ancestry tracing back to the Mongolian Baijite clan. He was born on May 5, 1900, and at the age of 15, he gained admission to Beijing Normal University, consistently ranking at the top of his class during his studies. After graduating, he successively worked at the Jing Shi Public No. 10… He served as the principal of the Seventh Higher Elementary School (now known as Beijing Fangjia Hutong Primary School) and the Seventh Higher Elementary School (located in the South Zongxue Hutong, south of Xidan Paizhou). In 1920, Bai Dazhou studied national pronunciation at the National Language Study Institute and was spotted by Li Jinxu. Mr. Li believed that he had a keen mind, was fluent in the national language, achieved excellent results, and was the best among his peers. He invited him to work together on the national language movement. Following that, Bai Dazhou devoted his life to this cause—participating in discussions, lectures, publicity, inspections, and editing related to national pronunciation.

In 1926, the National Language Unification Preparation Committee began to revise the “National Pronunciation Dictionary,” and the draft of the “Common Vocabulary of National Pronunciation,” published by the Ministry of Education in 1932, was all written by Bai Dazhou.

In 1924, Bai Dazhou was admitted to the preparatory program of Peking University, then entered the English department for undergraduate studies, and in 1928, transferred to the Chinese Literature department, studying under Qian Xuantong, Ma Youyu, and Liu Ban Nong, specializing in phonology and phonetics. At this time, he was already an executive member of the reorganized National Language Unification Preparatory Committee and the director of the organization department of the Chinese Dictionary Editing Office. He also served as the educational director of the Peiping Municipal Normal School (now Capital Normal University). While juggling multiple roles, he worked diligently, attending a language training class at the Institute of History and Philology of the Academia Sinica, studying dialect dictation under Zhao Yuanren. At the same time, he completed several works, such as “On the Evolution of the Northern Pronunciation’s Checked Tone,” “Study on Sound Classes in Jiyun,” “Statistics on Rhyme Sections of Guangyun,” “Guangyun General Inspection,” “Contemporary Reading Table for Checked Sounds in Guangyun,” among others. His academic spirit can be described as “seeking truth from facts, striving diligently, and markedly different from the ordinary,” which was an evaluation by Luo Changpei. His work in the National Language Council fully reflected the aforementioned academic spirit. He proposed individual initiatives, such as “Requesting the Ministry of Education to submit all various national language textbooks for the committee’s review,” “Requesting the committee chair to propose that all agencies and city street names add national pronunciation letters,” “Requesting various railway and postal offices to list place names and their pinyin for reference in pronunciation,” “Requesting the Ministry of Communications and the Ministry of Railways to promote national pronunciation telegrams,” and “Proposal to establish a National Language Printing Office,” among others. Matters proposed jointly with Wei Jianggong included: plans to establish a national language literature museum, specifically a national pronunciation printing house, and to run specialized… (text continues) The text translates to the following in English:

“Training institutes for Mandarin research, etc. He was a principal contributor to the ‘Mandarin Weekly’ and served as the Director of Academic Affairs at the ‘National Phonetics Lecturing Institute.’

However, fate was cruel. From late 1932 to January 1933, he lost five family members consecutively: his eldest son Lan, two daughters Ling and Ju, his wife Sheng Jianxi, and his father. The sorrow was beyond words. When his daughter Ling passed away, he wrote to Lao She, saying: ‘Ling-er has died… She drew her last breath at the same time as her mother was buried, which made me feel particularly mournful. At home, I was holding Da Zhuang, while my mother was holding Ju; four of us from three generations, the situation was extremely tragic. Now I have come to Xishan, living alone in the lowest courtyard of the Third Primary School; this vast place has only me. It is extremely cold, the wind is fierce, and the icy moonlight fills the courtyard. I stare across the window at the southern mountain, recalling the events of the past two weeks, and tears cannot help but flow!’ When Bai Fu-ren died, Lao She rushed to Beiping to comfort Bai Dizhou, only to find that ‘he was still holding on, crying silently, but his hands trembled when he served tea.’

Amidst immense sorrow, Fu Sinian appreciated Bai Dizhou’s writings and asked him to investigate the tone changes in the entering tone readings in Henan, Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Gansu. He traveled to Shaanxi to study dialects, seeking to relieve his distress. During this time, he investigated dialects across fifty sites in forty-two counties in Guanzhong, leaving behind a wealth of research materials. Upon returning, he went to Shanghai to record ‘Standard Mandarin Phonograph Records’ for the China Books Company. By the end of the year, he was invited by Liu Ban Neng to join the phonetics and music rhythm laboratory at the Peking University Research Institute as an assistant, where he completed the tonal curves for ‘The Changes of Entering Tone in Guanzhong’ and ‘The Experimental Record of the Four Tones in Guanzhong,’ which rivaled Lü Zuqian’s ‘Donglai Bo Yi.’ In the summer of 1934, he accompanied Liu Ban Neng to Guizui to investigate dialects. Unfortunately, Liu Ban Neng succumbed to returning fever and passed away. Bai Dizhou also fell ill; being young and deeply engaged in work, he first delivered a speech in Chang’an as a representative of the National Language Society, then attended the National Conference on Romanization of Mandarin in Zhengzhou, all while making a detour to visit his newlywed wife. He was truly exhausted and ultimately fell ill. On October 12, Bai Dizhou passed away at Lin Baoluo Hospital in Beiping. Lao She believed that Bai Dizhou had worked himself to death.

Bai Dizhou was a warm-hearted person, never hesitating to help others. In 1929, after returning from England, Lao She stayed at Bai Dizhou’s home. Seeing that he was over thirty and still unmarried, Bai Dizhou…” He became a matchmaker for Luo Changpei and Dong Luan, arranging for Hu Jueqing to go to Bai Dazhou’s home for part-time teaching, where she met Lao She for the first time. Through their subtle matchmaking efforts, this marriage was facilitated. When they became engaged, the three of them presented a “engagement commemorative gift,” and when they got married, Bai Dazhou and Luo Changpei were noted as introducers on the registration book. Naturally, Bai Dazhou and Lao She’s relationship extended beyond this single event; they shared a common language. After the publication of Lao She’s early novels “The Philosophy of Old Zhang” and “Zhao Zi Says,” Bai Dazhou immediately pointed out his mistake of mixing classical and vernacular Chinese together, advising Lao She not to take shortcuts in this way. Initially, Lao She thought little of it, believing it was a matter of appealing to both refined and popular tastes, but later he realized this was an act of laziness. Literary creation should encompass both thought and language.

Qian Xuantong’s classes were very popular, but he had a habit of avoiding the preparation of handouts. Bai Dazhou attended Qian Xuantong’s philological lectures at Peking University, taking notes diligently with the intention of compiling a handout on ancient phonology, which Qian Xuantong would then review and publish. Naturally, Qian Xuantong was eager for this. On September 20, 1934, when Qian Xuantong was teaching, Bai Dazhou brought his new wife Xu Rong to listen to the class and take notes. Qian Xuantong was very curious and asked Bai Dazhou after class why he had brought his wife along. Bai Dazhou replied, “Next Thursday I will be in Zhengzhou, and I asked her to take notes. Today, I’m practicing having her take notes with me.” The article “The Evolution of Ancient Phonology” published in the 238th issue of “National Language Weekly” in April 1936 is based on the notes Bai Dazhou took while listening to Qian Xuantong’s lectures on phonology. This is a valuable piece of ancient phonological material, but unfortunately, the content is too brief. In the editor’s footnote that accompanied the publication of this note, it stated: “What is published now is only the beginning; after Mr. Bai had just one lecture, he passed away. He only recorded this one session, so what is published is just a little…” Judging by the tone of the editor’s note, it is very likely that it was written by Qian Xuantong himself. Li Jinxi expressed his feelings about this in “Biography of Mr. Qian Xuantong,” saying: “The ‘Ancient Phonology Study’ is strictly speaking Mr. Bai’s posthumous work, and it has now also become Mr. Qian’s posthumous commentary.”

There is also an interesting incident when Liu Banong appointed Bai Dazhou as a teaching assistant in his laboratory… Here is the translated text from Traditional Chinese to English:

Li Jinxi and Qian Xuantong felt that this was simply undermining their own interests. Qian Xuantong wrote in his diary, “Is there really anyone in the world who would publish a book related to another without consulting the person involved? I shall transfer this letter to Bai Dazhou and Wei Jianggong to clarify my thoughts, and then protest to Liu Banrong.” The later generations viewed these masters as being red-faced over Bai Dazhou, while in Bai Dazhou’s heart, every predecessor was someone he respected. Although Li Jinxi had never been his teacher, he was a significant mentor to him, leading to many collaborations, like co-editing “Zi Yin Fu Hao Wu Shi Zi Tong” (Phonetic Symbols for Self-Study, June 1929) and “Peiwen New Rhyme” (published by Peiwen Studio in Beiping).

Huang Xuezhou, who served as the deputy chief of staff for the transportation command of the four routes of Long, Jin, Ping, and Dao, and simultaneously as the director of the Longhai Railway Administration, got to know Bai Dazhou while investigating the entering tone along the Longhai Railway and began to engage with phonetics and Mandarin Romanization. He was responsible for the affairs of the National Mandarin Romanization Conference in 1934 and self-published records to promote Mandarin Romanization. After the death of Bai Dazhou, he wrote an elegy titled “Elegy for Mr. Bai Dazhou,” which contains a passage: “Mr. Bai! Have you really passed away? Have you truly followed Mr. Banrong to research the materials you collected forever? But, will the fruits of your research still be able to reach the world? Alas! This is a dream that absolutely cannot be realized! For the organization of your posthumous works, we comrades share the responsibility; even for someone as foolish as I, I have a part of the responsibility for the organization. How can I let your works sit idly? If I were to truly put them aside, how could I face Mr. Bai? How could I face the people of the nation? Let us strive! We cannot become disheartened by this loss; we must fulfill the unfinished aspirations of the deceased. Mr. Bai, you in the underworld may still be aware, and perhaps you could close your eyes in peace? However, how can we endure such an unfortunate loss? I cannot help but beat my chest and weep.” This passage expresses the heartfelt thoughts of many colleagues in the Mandarin movement regarding Bai Dazhou and this cause.

Portrait of Bai Dazhou

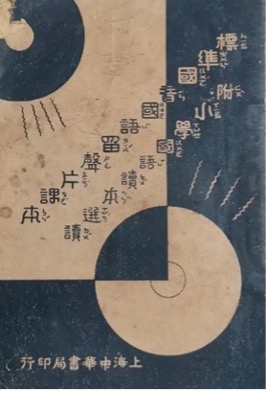

Record by Bai Dazhou Records of Guan Chang in Asia

References:

“The Collected Works of Luo Changpei” (Volume 10), Shandong Education Publishing House (November 2008)

“Self-Narration of Lao She” (Annotated Edition), Lao She, annotated by Xu Deming and Yi Hua, China Publishing Group Modern Publishing House (October 2018)

Lao She’s essay “Crying for Bai Dizao”

“The Diary of Qian Xuantong” (Compiled Edition), edited by Yang Tianshi, Peking University Press (August 2014)

“The 1934 National Conference on Mandarin Romanization and its Connection to the Longhai Railway,” The Paper (July 21, 2022)